Hori Toshiro: The Living Legacy of Shino and Setoguro Teaware

Ecrit par Team MUSUBI

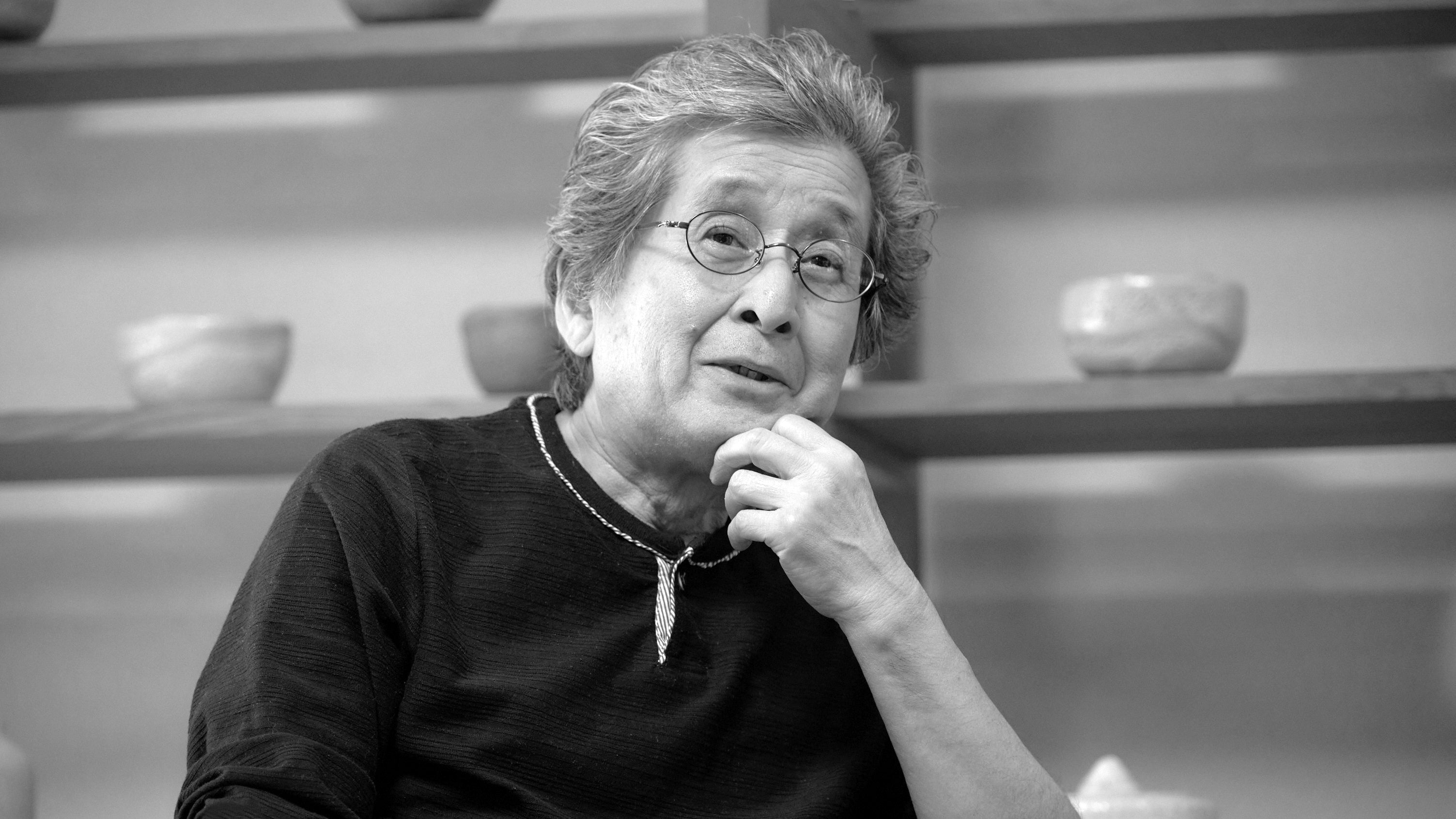

Fiery glimpses of orange-red beneath a soft white glaze. Intensely reflective black that seems to shimmer under the surface. These are the matcha bowls of Hori Toshiro, master of Mino ware and Kani City Intangible Cultural Property holder of Shino ware pottery. Hori spent fifty years working alongside the Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage, Kato Kozo, inheriting traditional Japanese ceramic techniques while pursuing his own path. Now, Hori pays it forward by advising the younger generation in historic Mino ware techniques.

This article will trace Hori’s journey as an artist from a chance encounter to mastery of the craft, while diving into the beauty and techniques of white Shino ware and black Setoguro. Both of these styles developed in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603 CE) and became very influential in tea ceremony aesthetics. Yet not long after, their production was interrupted for over 300 years. Finally, the tradition was revived in the 1930s by pioneering artisans like Arakawa Toyozo. This is what Hori has inherited and passes down today.

Table of contents

The Chance Encounter That Led to a Life of Craft

Born in Kobe to a family with no connection to a technical or artistic field, Hori never expected to end up pursuing a career in ceramics. It was when he was browsing in a bookstore that he first encountered the field.

Flipping through art books one day during his first year in university, Hori came across a section about Kato Kozo—the man who, unbeknownst to either of them, would soon become his teacher.

Recalling that moment, Hori says, “There was a photo of his face. Just from that face photo, I got the feeling, ‘There’s something about this person.’ Sometimes you get that feeling from someone’s atmosphere, right? Like an aura.

“I thought it might be interesting if I visited him. I thought if I talked with him, I might find some kind of hint—about what I should do from here on out, what kind of things I should pursue, how I should live my life moving forward. He seemed like someone who would have a hint.”

Although Hori lived in Wakayama at the time, he made the multi-hour trip to where Kato lived in Tajimi, Gifu Prefecture, to meet him. Within a year, Hori had quit his university program and moved to Tajimi to be Kato’s full-time live-in apprentice. That was in 1976.

They would live and work side-by-side for the next fifty years.

Living and Working Alongside a Living National Treasure

Kato Kozo was recognized in 2010 as a nationally designated Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage for his Setoguro technique. So what was it like learning from a potter whose dedication to the field would lead him to become a Living National Treasure?

Hori explains, “It really wasn’t ‘learning’ so much as watching and absorbing. In order for Kozo-sensei to do his work, I had to understand what he would need next, the flow of the work. That was the first thing.

“I did my own work and had my own tasks, but unless I brought what I made to him and had him look at it, I wouldn’t receive advice on how I should do things.

Being a live-in apprentice was “nothing like school,” Hori says. It was all-encompassing.

“Pottery existed within everyday life. Because—how should I put it—being taught was never the basic premise. Everything was done together: planting flowers and grasses, making the garden. Everything, everything was daily life. Within that life, pottery existed. It’s not like pottery was separate. I was taught everything, learned everything."

“Within life itself, we experienced what was beautiful.”

Building Everything from Scratch

Hori didn’t come from a pottery family, which came with its disadvantages. It meant he had to prepare tools, workspaces, and build other resources from scratch.

Even working with a teacher, “I stayed with him, but our work was separate. I had to do my own work. It truly was a start from zero.”

It’s somewhat unusual in a field where craftspeople often have the backing of several generations of artisan family members to support them. But Hori’s tone remained optimistic throughout our conversation.

“I never felt disadvantaged because of it. I could witness Kozo-sensei’s first-rate work up close—that opportunity is rare. If I had been an outside apprentice, I wouldn’t have been able to see everything, even for glazes: what sequence, what method, what thinking, what flow. If you’re not there, you can’t see that.

“Being there to see it was so fortunate.”

Working alongside Kato for so many years is part of what allowed Hori to go so in-depth into the world of Mino ware—in particular, the revived traditional techniques of Setoguro and Shino. These next sections will take a closer look at these art forms and how Hori creates his work.

Setoguro: Jet-Black Tea Ware

Literally meaning “Seto black,” Setoguro wares are prized for their jet-black, glossy surfaces. This unique finish is achieved by removing a piece from the kiln mid-firing and cooling it rapidly by immediately plunging it into cold water. One of the biggest challenges with Setoguro is judging when to pull it from the kiln.

Hori’s pieces are fired in an anagama, a type of traditional wood-fired kiln that has been used in Japan for over 1,600 years. Built up a slope and consisting of a single firing chamber, firing with these kilns gives a unique presence to ceramics. Yet the temperature of the flames and the inner firing environment can be difficult to control, requiring a delicate understanding of the kiln’s inner workings. For more on types of Japanese kilns, read our article here.

Hori explains what it’s like to fire Setoguro. “Setoguro is fired together with Shino in a strong reduction environment—firing with little oxygen. Around 900 to 950°C (1652–1742°F), the reduction begins. You have to watch the flame in the kiln. When it retreats, you add more wood, the flame bursts out again, and you repeat that cycle.

“Around 1070°C (1958°F) to just before 1100°C (2012°F), the flame starts becoming sticky, viscous—like it clings. When it reaches that state, you look into the kiln and judge.

“At that point, the inside of the kiln is not red anymore—it’s pure white. So bright you can’t tell what you’re seeing. It’s dazzling. In that whiteness, you look for signs of how the glaze is melting. You use a metal rod and touch the surface. If it clings like sticky rain, that’s a sign.

“You check both the front and back of the kiln. The front melts faster because the fire hits it directly. The back you can’t see, but when you judge that the back has melted enough, that’s when you pull it out. I use a thermometer, but it’s not accurate—just a rough estimate. So I decide with my own eyes.

“And when you feel ‘Now!’ you pull the piece out and plunge it into water with a hissss. It immediately turns completely black.”

The black of Hori’s Setoguro pieces is complex, deeper than a single color.

Hori explains, “In my recent Setoguro pieces, you can see black that appears reddish, greenish, or bluish. ‘Black’ isn’t just black. Within it, many colors are hidden. The question becomes: how do you draw them out?”

Adjusting the flames, the timing of extraction, and how the temperature increases inside the kiln are all part of the art of creating those fascinating blacks. Every piece is one-of-a-kind, an irreplicable product of a moment in time.

Shino: White and Softly Textural

Shino ware, on the other hand, is characterized by its milky white glaze and textural surface. Known as kairagi, this crackled and porous surface pattern forms as the feldspar-based glaze contracts during firing. This creates a color contrast as glimpses of the clay body emerge from underneath. In Shino teaware, the kairagi pattern deepens with use as tea slowly seeps into the crackles. The ceramic continues to develop, like a living thing that matures alongside the user.

This quality is highly valued in tea ceremony culture. “When a tea bowl is cherished, handled carefully, and used well, the stains gain dignity,” Hori says. “That is a uniquely Japanese cultural sensibility.” For this kind of ceramic, each mark of use is a sign that it is “a treasured object used for years. When you acquired it, when you used it—everything is included in the story of the vessel.”

One of the keys to Hori’s Shino ware is the clay mixture. As part of his ongoing work to revive and pass down the Shino of 400 years ago, Hori uses a mix of local clays: a very soft, crumbly clay known as mogusa clay, and a stickier clay from deeper soil layers. Mogusa clay is hard to work with because of its unstable consistency, yet increasing its ratio gives a piece a softer feel. It also has historical significance. “It feels closer to older pieces excavated from ancient kiln sites,” Hori explains.

Hori’s current efforts as an artist involve exploring what he can do with mogusa clay. “How far can I push it? What is the limit of the clay’s workability?” It’s all part of his continuing journey as an artist.

Raising the Next Generation with Deidei

Pushing artistic boundaries isn’t the only thing Hori is working on these days. He also provides technical guidance to deidei, a ceramics brand run by his son, Hori Taichi.

Deidei’s aim is to help preserve Mino ware techniques like Shino, ki-Seto, and Oribe by bringing them into everyday households. Although these styles are traditionally only seen in high-end teaware, deidei’s line of everyday tableware makes them more accessible.

Just like how Hori Senior entered the world of ceramics through his chance encounter with Kato Kozo, he hopes that deidei will increase opportunities for people to encounter Shino and other traditional Mino ware. He dreams of creating new possibilities and broadening horizons.

“If only a small number of artists exist,” he explains, “that might be fine as ‘art,’ but little by little, the techniques will disappear. We’d end up in the same situation again,” as before Shino and Setoguro were revived nearly a century ago.

Hori gestures to the Shino ware cups we’ve been drinking tea from during the interview.

“Art pieces are not easy to use in an ordinary household. But yunomi like these—you can use them every day. If they’re used daily, many people can handle them. We have to leave behind such opportunities.”

Legacy and the Future

Kato Kozo passed away in 2022. Since then, Hori has reaffirmed his commitment to passing down his traditional techniques.

“Setoguro, especially, feels like a kind of mission. It’s something I must not abandon. Since Kozo-sensei passed away, there’s no one else nearby who has seen this work up close. Other disciples exist, but no one else fires an anagama like this. If I don’t produce works from this kiln, the technique will vanish instantly.”

Hori notes that the Agency for Cultural Affairs created archival films for the National Diet Library. These documents Kato’s work and kiln firings in an effort to preserve traditional culture. But having a record isn’t the same as having living people able to make the work themselves.

“Kozo-sensei put his life on the line for this work. As someone who was his disciple, I feel I must carry this on.”

Hori’s works are deeply reflective of history and steeped in respect for his teacher and tradition. They also stand on their own as superior teaware for their refined grace and elegant beauty. But the artistic merit of Hori’s work goes further even than that. It comes from being created by the hands of someone whose daily life is inseparable from the process of creation. Who took a chance on a person and discovered his life’s work. There is poetry in that.

Laisser un commentaire

Ce site est protégé par hCaptcha, et la Politique de confidentialité et les Conditions de service de hCaptcha s’appliquent.