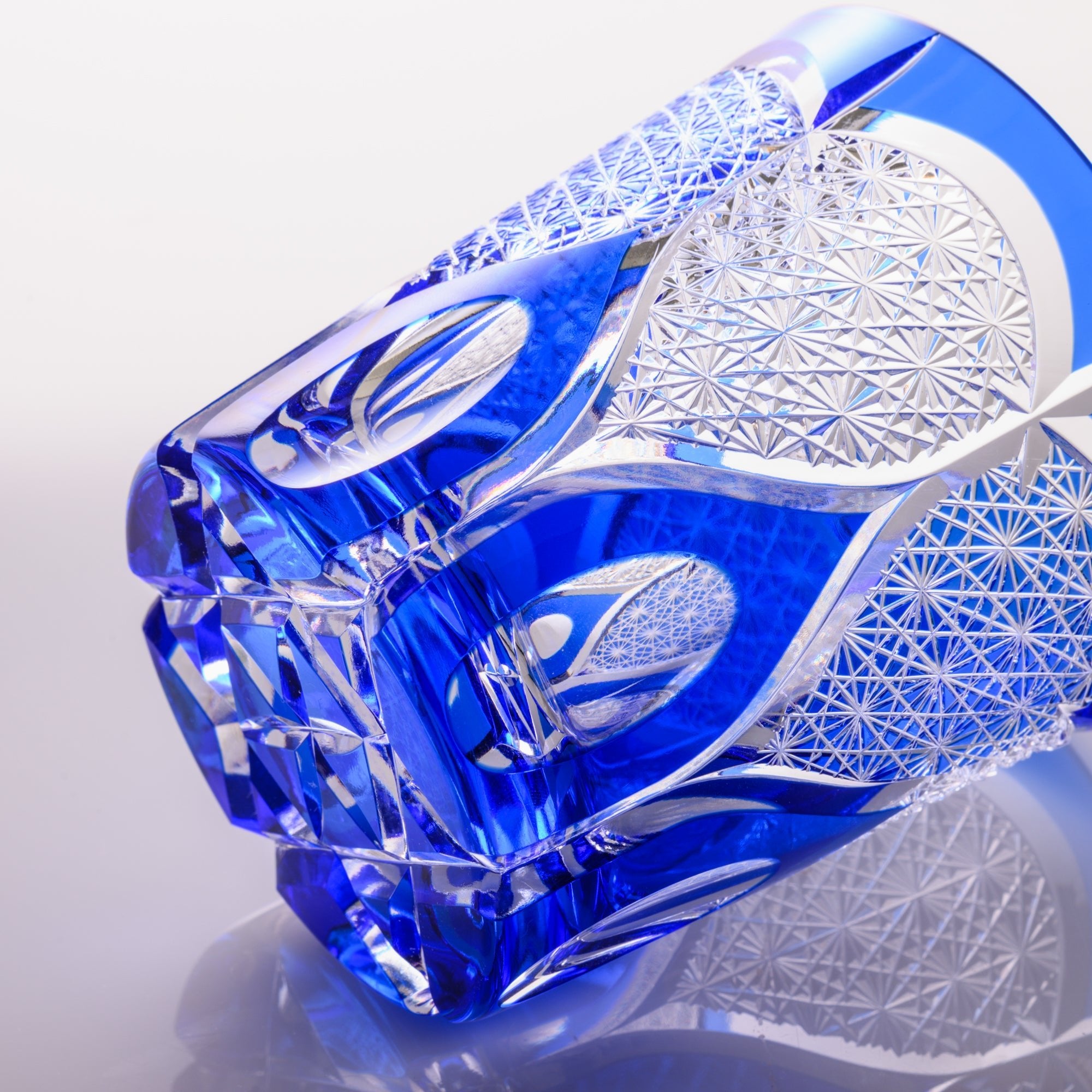

Cristales preciosos de la ciudad de Edo

Edo Kiriko y Edo Glass

Tokio, la capital de Japón, es también un centro de artesanía. Entre sus numerosas tradiciones, el vidrio Edo y el Edo Kiriko son tipos de cristalería que se han transmitido de generación en generación durante unos 200 años en Edo, el antiguo nombre del centro de Tokio.

Sus superficies luminosas reflejan siglos de artesanía, nacida en lo que una vez fue Edo y aún prospera en el Tokio moderno.

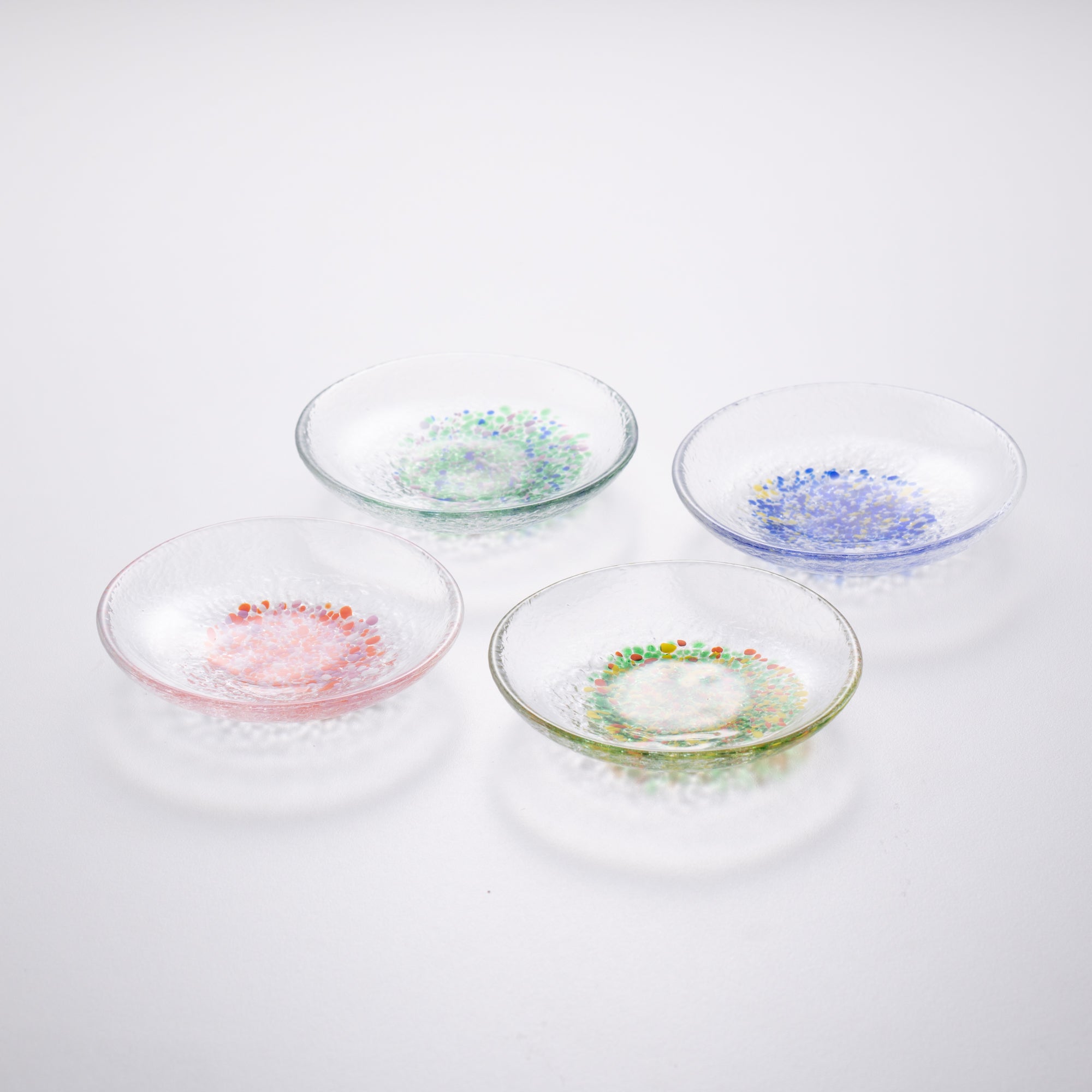

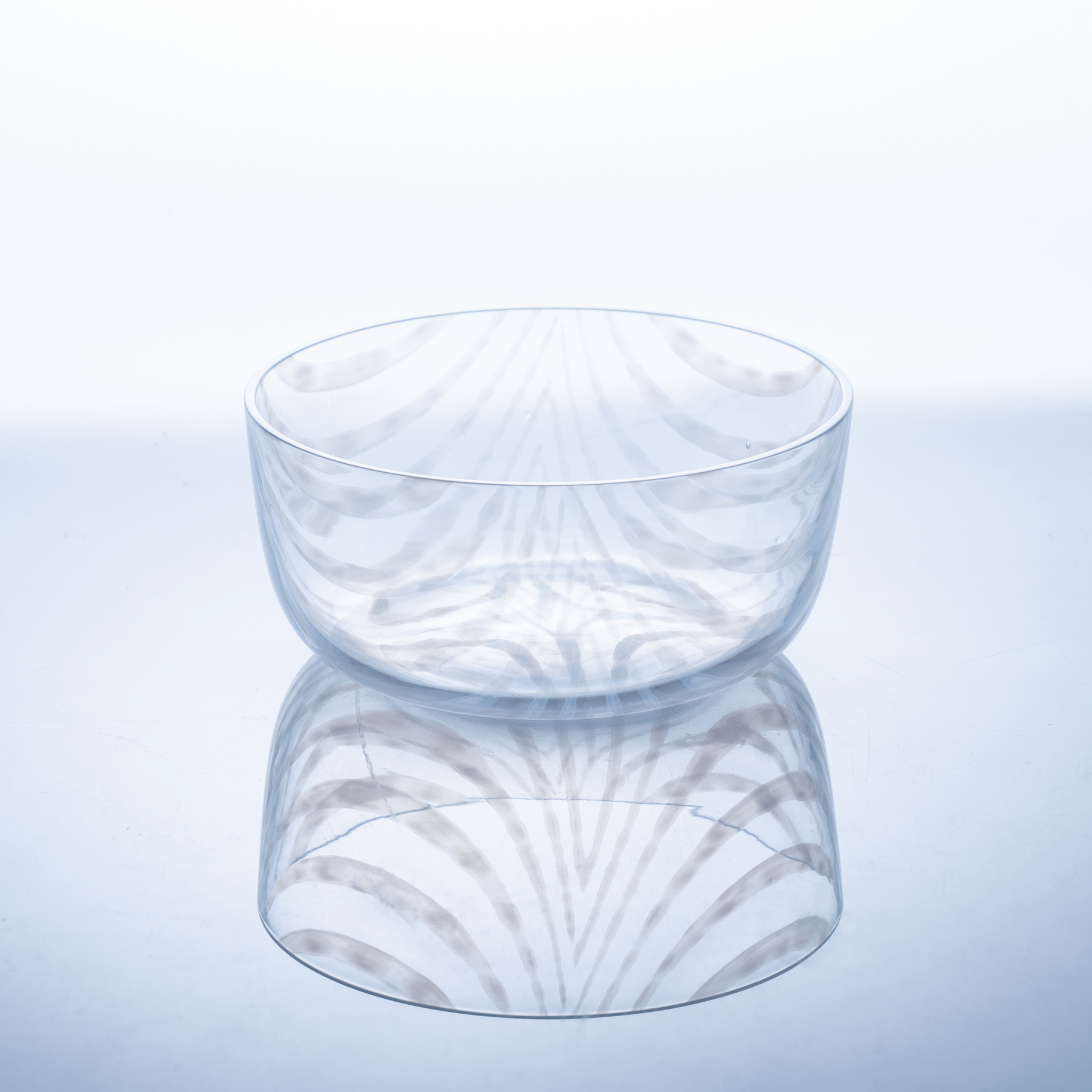

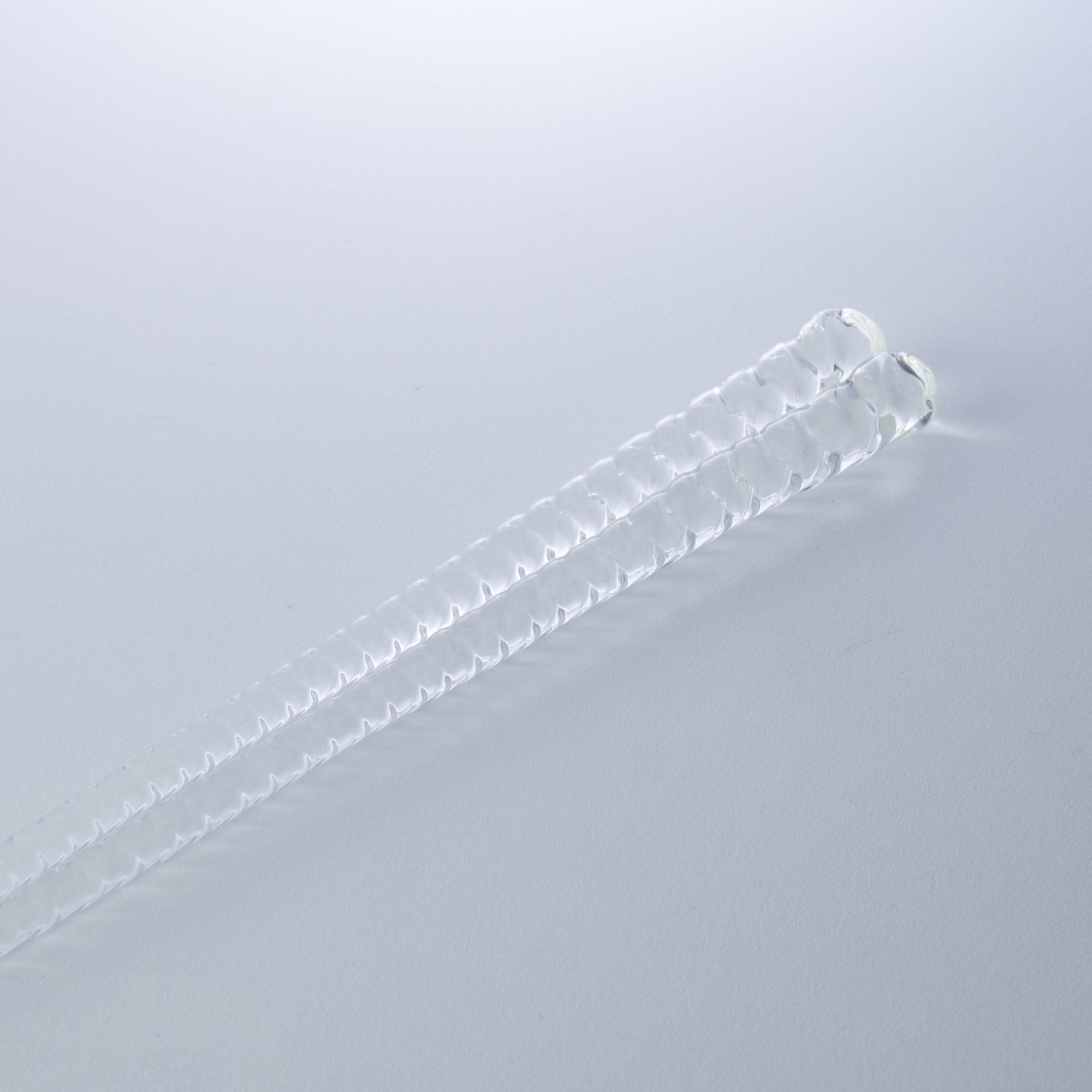

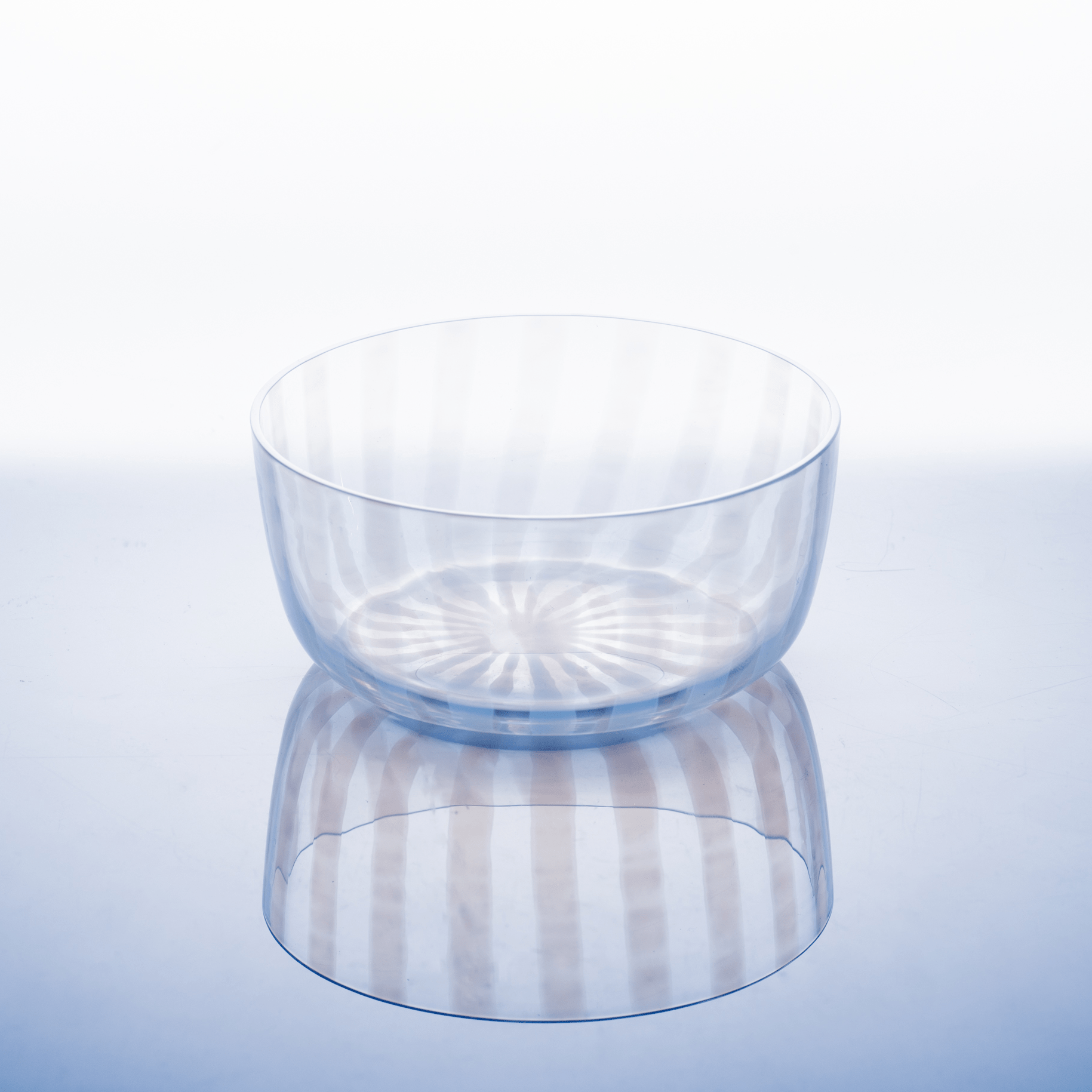

Acerca de Edo Glass

El vidrio Edo es una artesanía que conserva técnicas heredadas del período Edo. A diferencia de los artículos producidos en masa, cada pieza es única, con sutiles variaciones y la calidez que solo la artesanía puede ofrecer. Estas piezas son elaboradas por hábiles artesanos en los alrededores de Tokio, y su discreta belleza les ha ganado popularidad tanto en Japón como en el extranjero. En 2014, el vidrio Edo fue reconocido oficialmente como artesanía tradicional por el Ministerio de Economía, Comercio e Industria de Japón.

Historia del vidrio Edo

El vidrio llegó por primera vez a Japón a través de importaciones portuguesas y holandesas durante el período Sengoku (1467-1600 d. C.). La producción de vidrio soplado comenzó en Edo alrededor de 1711, y para el siglo XVIII, ya se elaboraban artículos de vidrio como campanas de viento. kanzashiLas tazas de sake se habían convertido en parte de la vida cotidiana. En 1879, Tokio presenció el auge de las fábricas de vidrio de estilo occidental, pero muchos talleres se perdieron posteriormente debido a grandes desastres en el siglo XX. Aun así, la artesanía perduró, y el vidrio Edo actual continúa ese legado, pieza a pieza artesanal.

Acerca de Edo Kiriko

Edo Kiriko es una artesanía tradicional que realiza intrincados grabados sobre la superficie del vidrio Edo. Alrededor de veinte patrones geométricos se tallan con una precisión excepcional, creando un brillo joyero al reflejar la luz. Especialmente en piezas de vidrio coloreado, el contraste entre la vibrante superficie y el vidrio transparente crea un efecto nítido y llamativo. Estos refinados cortes se realizan sin bocetos detallados, solo se dibujan guías sencillas directamente sobre el vidrio, un método exclusivo de Edo Kiriko. El Edo Kiriko fue designado oficialmente como Artesanía Tradicional por el Ministerio de Economía, Comercio e Industria de Japón en 2002.

Historia de Edo Kiriko

El Edo Kiriko surgió en 1834, cuando un comerciante de vidrio llamado Kagaya Kyubey grabó por primera vez vidrio con polvo de piedra granate. La técnica maduró en la era Meiji, cuando el artesano inglés Emanuel Hauptmann introdujo métodos occidentales. Con el tiempo, surgió un estilo característico: cortes profundos sobre vidrio coloreado, superpuestos sobre vidrio transparente. A partir del período Taisho (1912-1926 d. C.), el Edo Kiriko se convirtió en un arte decorativo muy apreciado, que aún prospera en Tokio.

Elaboración de Edo Kiriko

Waridashi/Sumi-tsuke

En la producción de Edo Kiriko, no se dibujan bocetos detallados para el diseño. En su lugar, se sigue un proceso llamado waridashi (dividiendo) o sumi-Tsuke El entintado se utiliza para marcar el diseño directamente sobre el vidrio. A estas marcas se le añaden líneas finas y superficiales talladas con una rueda de afilar, que sirven de base para el diseño final. Tan solo con estas líneas tenues, cobran vida los intrincados motivos de Edo Kiriko.

Arazuri–Sanbangake

Para el grabado de Edo Kiriko, los artesanos utilizan Kongo-sha, un polvo grueso de granate, junto con ruedas metálicas giratorias. En la etapa inicial llamada arázuriEl diseño está tallado de forma tosca utilizando la veta más gruesa. A esto le sigue sanbangake, que utiliza abrasivos más finos para refinar las líneas. Aunque no se dibuja un boceto, el grosor y la profundidad de cada corte se logran con notable precisión, guiados únicamente por la habilidad y el equilibrio del artesano.

ishikake

En la etapa final de tallado llamada ishikakeLos patrones de los pasos anteriores se refinan con un disco de afilar. Este proceso suaviza la superficie grabada y permite obtener detalles intrincados que no se pueden lograr con ruedas de metal. Como paso final del corte, el ishikake juega un papel clave para determinar la claridad y el acabado de la pieza. El trabajo debe realizarse con sumo cuidado para evitar marcas toscas.

Migaki

Después del ishikake, la superficie del vidrio se ve turbia, como vidrio esmerilado. La etapa de pulido, llamada migakiRestaura la transparencia y realza el brillo característico de Edo Kiriko. Con agua y polvo de pulido, los artesanos pulen la pieza con discos de madera de paulownia o sauce, así como con discos de cerdas o de banda adaptados al diseño. Finalmente, se utiliza una rueda de pulido de tela, conocida como habuban—se utiliza para crear un acabado brillante y refinado.

Artículos relacionados

Filtros