Kyo Ware y Kiyomizu Ware

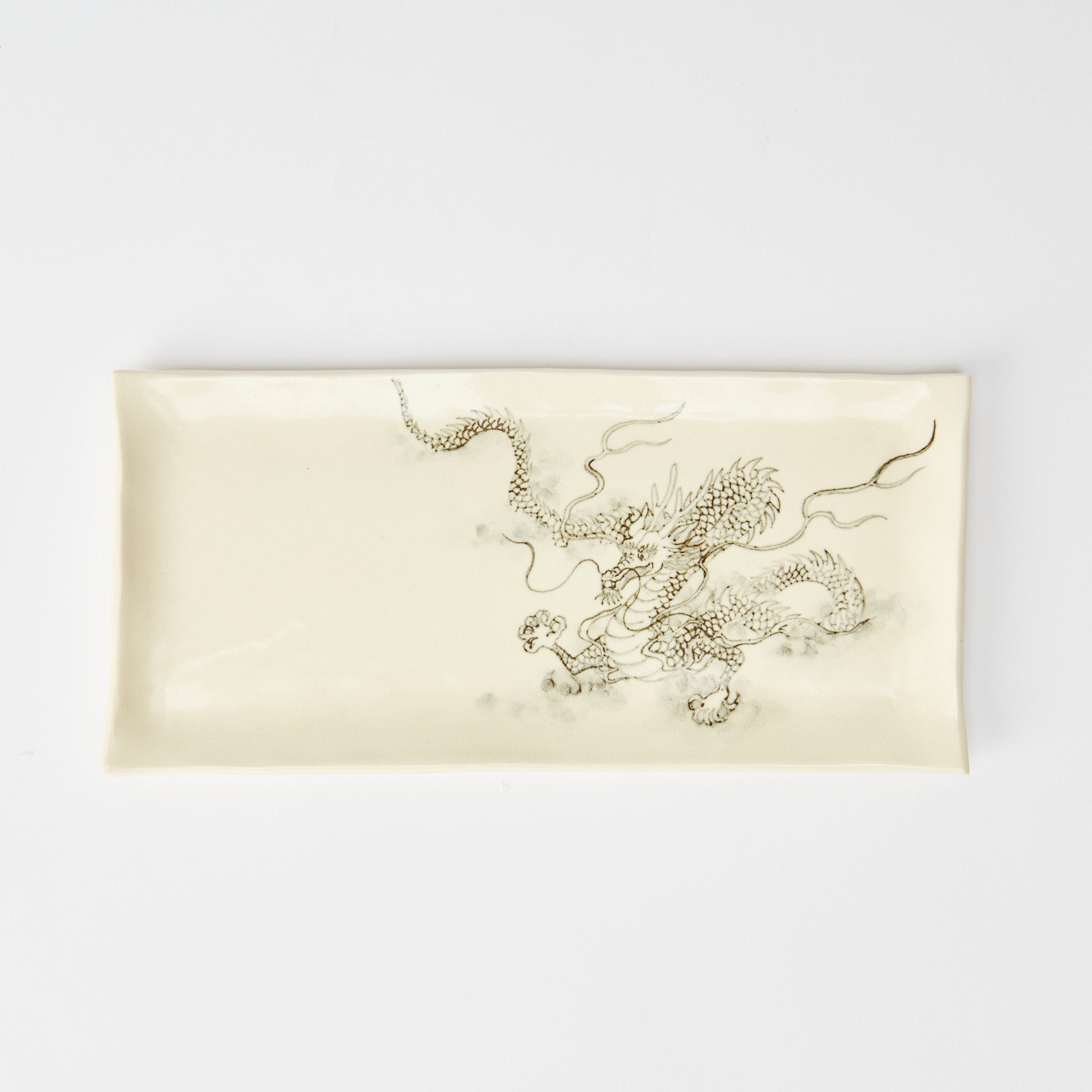

La cerámica Kyo y la cerámica Kiyomizu, conocidas colectivamente como Kyo-yaki y Kiyomizu-yaki, son estilos cerámicos célebres de Kioto. Conocidos por sus vibrantes diseños, formas finamente esculpidas y dedicación al detalle artesanal, estos artículos reflejan el distintivo sentido de la belleza y el refinamiento artístico de Kioto.

Caracterizadas por una diversidad cultivada desde hace mucho tiempo, las cerámicas Kyo y Kiyomizu se han inspirado en técnicas y estilos de las tradiciones alfareras de todo Japón, evolucionando hasta convertirse en una forma de arte ricamente expresiva y distintivamente kioto. Reconocidas como Artesanía Tradicional de Japón en 1977, siguen siendo apreciadas por su riqueza cultural y atractivo cotidiano.

Kioto, la capital histórica de Japón, ha sido testigo de una rica historia, bellamente reflejada en la evolución de los estilos de la cerámica Kyo y Kiyomizu. Estas cerámicas abarcan desde diseños ornamentados hasta piezas más sencillas y rústicas, cada una con una calidez y presencia serenas que invitan a una sensación de conexión con cada uso.

Conocidas por su exquisito diseño y funcionalidad, estas piezas de cerámica representan motivos estacionales y símbolos auspiciosos, combinando practicidad y elegancia. Cada pieza refleja la personalidad única de su creador. Por ello, se considera un símbolo del perdurable legado artístico de Kioto y se valora por su importancia histórica y su excepcional artesanía.

Durante la época de Kioto como capital de Japón, los maestros del té y la nobleza cortesana favorecían una cerámica que rompía con los estilos imperantes, priorizando formas y colores distintivos. Esta demanda propició la creación de talleres especializados que producían piezas únicas para uso ceremonial. La meticulosa artesanía implica que la producción siempre ha sido limitada, lo que convierte a la cerámica Kyo y la Kiyomizu en piezas raras y muy apreciadas.

Sin definirse por un solo estilo, la cerámica Kyo y la cerámica Kiyomizu destacan por su diversidad estilística. Cada artesano combina diversos métodos de moldeado, como la construcción manual, el torno y la fundición en barbotina, junto con técnicas decorativas como algúntsuke y pintura de esmalte sobreesmalte. A pesar de esta variedad, todas las piezas comparten una elegancia refinada y una artesanía soberbia, uniéndolas en una obra artística cohesiva.

La producción de cerámica en Kioto avanzó significativamente durante el período Momoyama tardío y el período Edo temprano (finales del siglo XVI y principios del siglo XVII), particularmente con la introducción de noborigama (hornos de ascensión) en zonas como Awataguchi. Durante el periodo Edo (1603-1868 d. C.), la cerámica de Kioto floreció aún más, ya que los utensilios de té se volvieron muy codiciados por maestros del té, nobles de la corte y señores feudales. Nonomura Ninsei, activo alrededor de 1647, se hizo famoso por sus elegantes diseños de esmalte sobre vidriado, mientras que su discípulo Ogata Kenzan colaboró posteriormente con su hermano, Ogata Korin, para crear platos de estilo Rimpa que contribuyeron a definir una estética distintiva de Kioto.

A finales del período Edo, surgieron alfareros como Okuda Eisen y Aoki Mokubei, quienes impulsaron la artesanía mediante la innovación y el resurgimiento de estilos clásicos. A Eisen se le atribuye la primera cocción exitosa de porcelana en Kioto. Durante el período Meiji (1868-1912 d. C.), la industria alfarera de Kioto enfrentó desafíos tras el traslado de la capital a Tokio, pero artistas y comerciantes se volcaron en la exportación y la innovación técnica. En la era Taisho (1912-1926 d. C.), la industria se expandió a las zonas circundantes y, a pesar del auge de la producción en masa en otros lugares, los talleres de Kioto continuaron produciendo utensilios de té artesanales. Estos pequeños talleres ayudaron a preservar el legado artesanal de la región durante un período de gran transformación.

Artículos relacionados

Filtros