10 June 2024

Tatami Change

Presenter

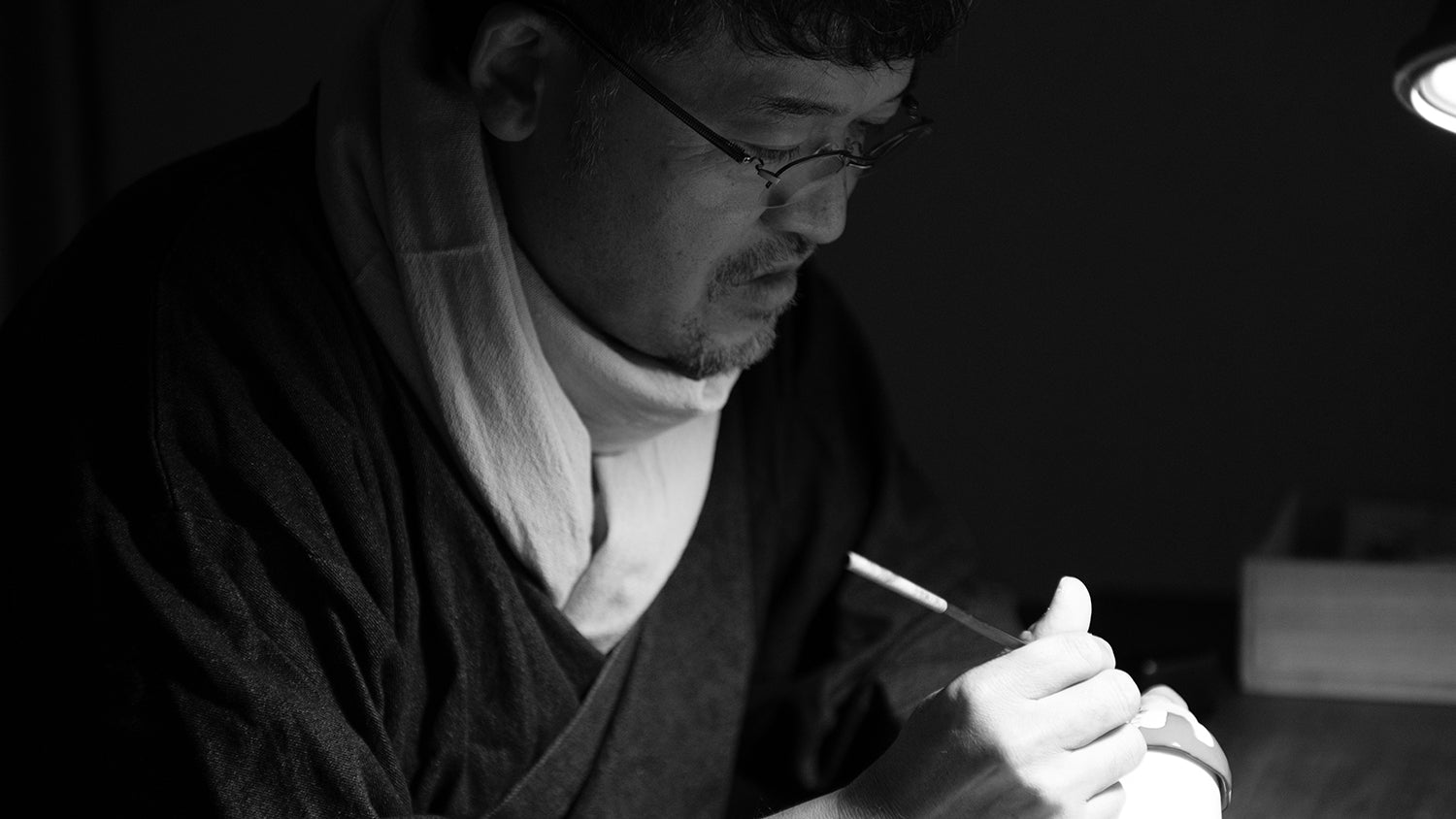

Michael Pronko

Michael Pronko is a Tokyo-based writer specializing in murder, memoir, and music. He is renowned for his writings on Tokyo life and character-driven mystery novels, such as "The Last Train," which have earned awards and received five-star reviews.

The three men were in and out in twenty minutes. Their only tools were a marking pen and a hand-held hook. Kneeling, they marked the position with the pen before leaning down, sinking in the hook, and hoisting my tatami mats up and out of the floor. Balancing the heavy mats between hook and hand, they moved through the house in a single motion to the entryway, where they slowed to slip on their shoes, and continued to their van where they laid the mats in a neat pile in back.

When they’d removed the twelve mats from two six-mat rooms, one upstairs and one downstairs, I followed them outside. They were taking the mats to their workshop. I wanted to go with them and spend the afternoon watching them refurbish the mats, but it was starting to snow, and I had things to do in the house before they returned.

I watched the three tatami specialists, two generations, hop into their van after promising to return that afternoon. They’d spend the day stretching new igusa rush matting across the top, realigning the base, repairing the spots my computer chair had crumpled, and adding new heri brocade borders which I selected from sample boards when the youngest of the tatami specialists came to my house the week before.

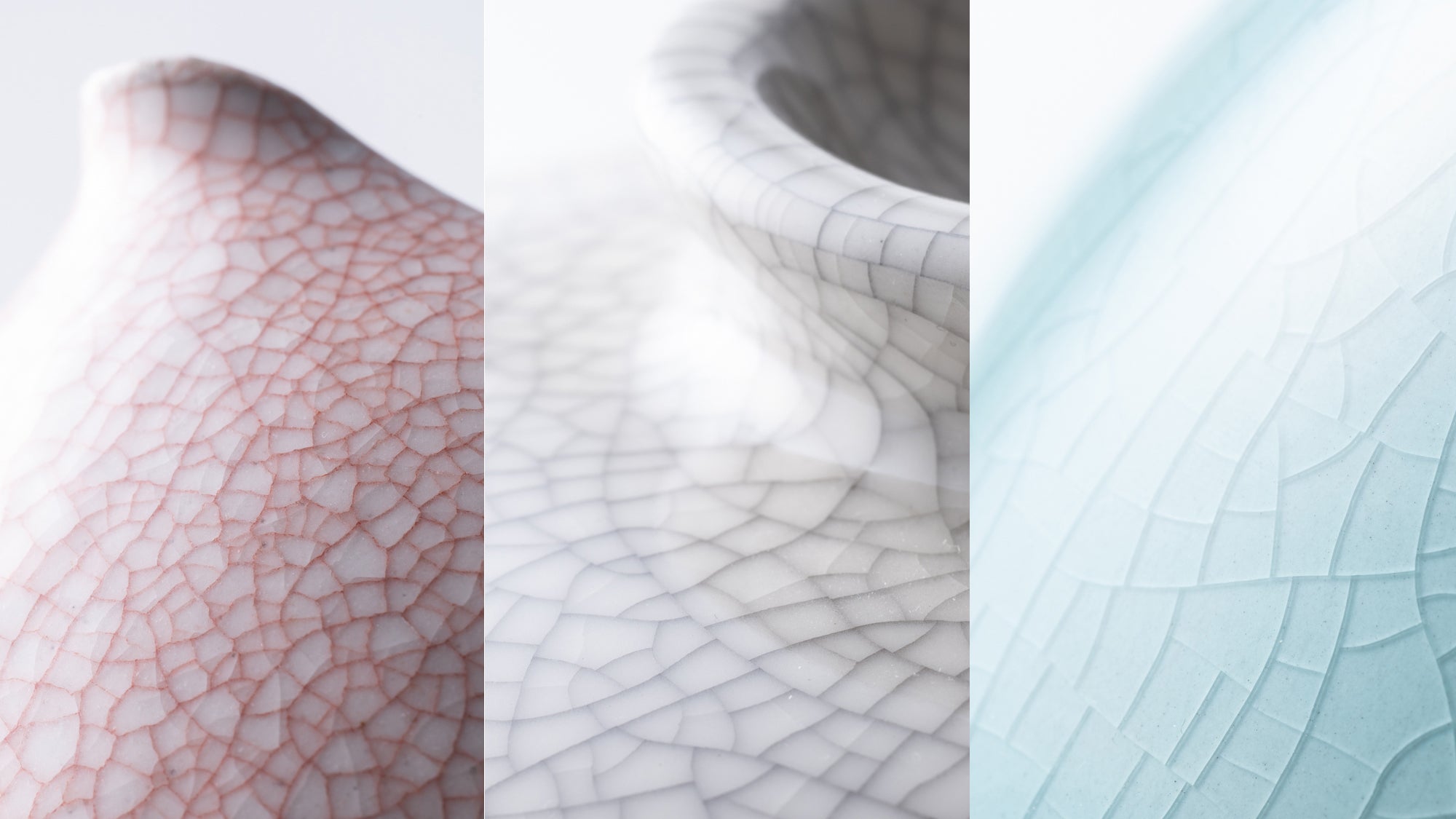

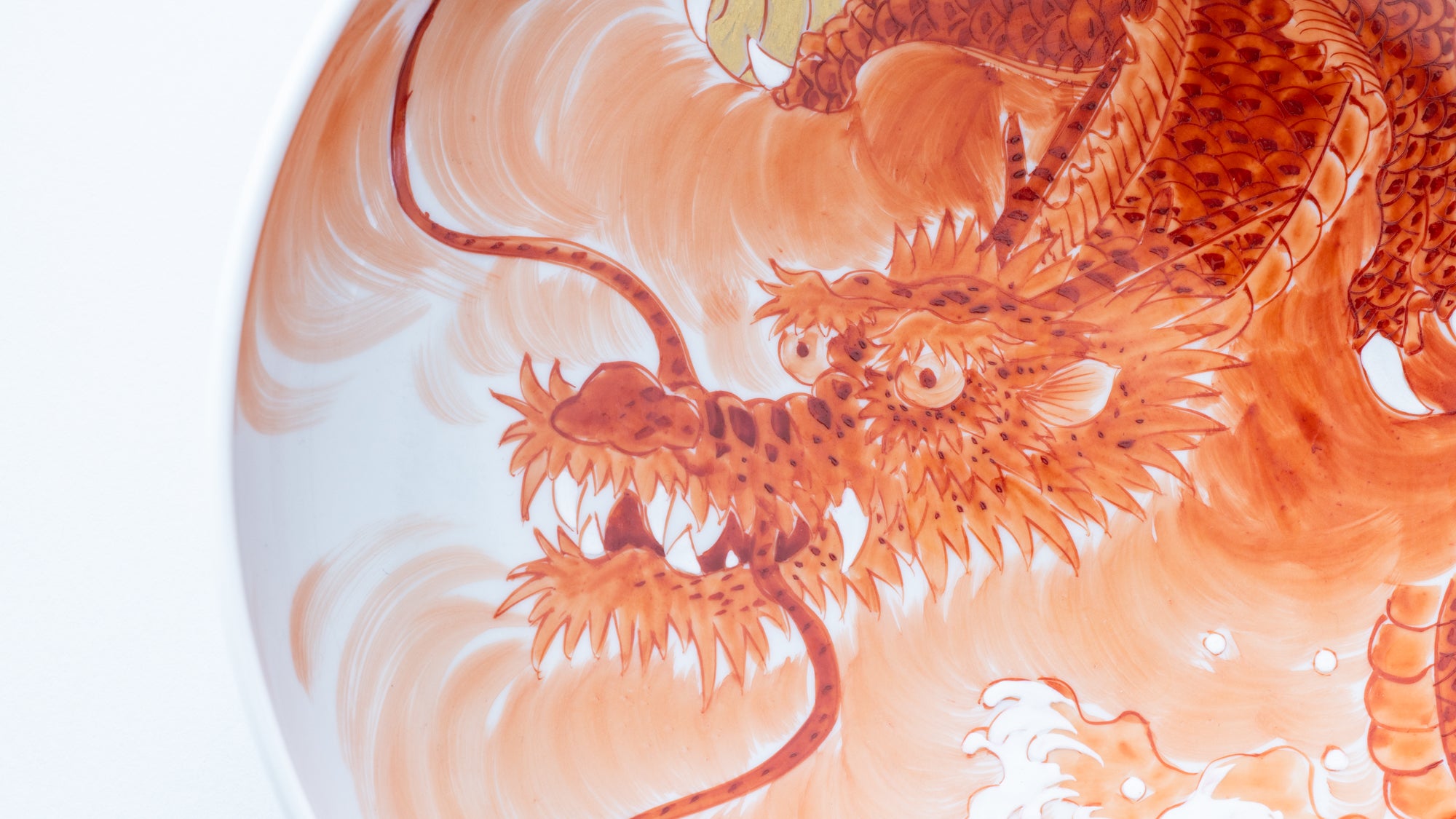

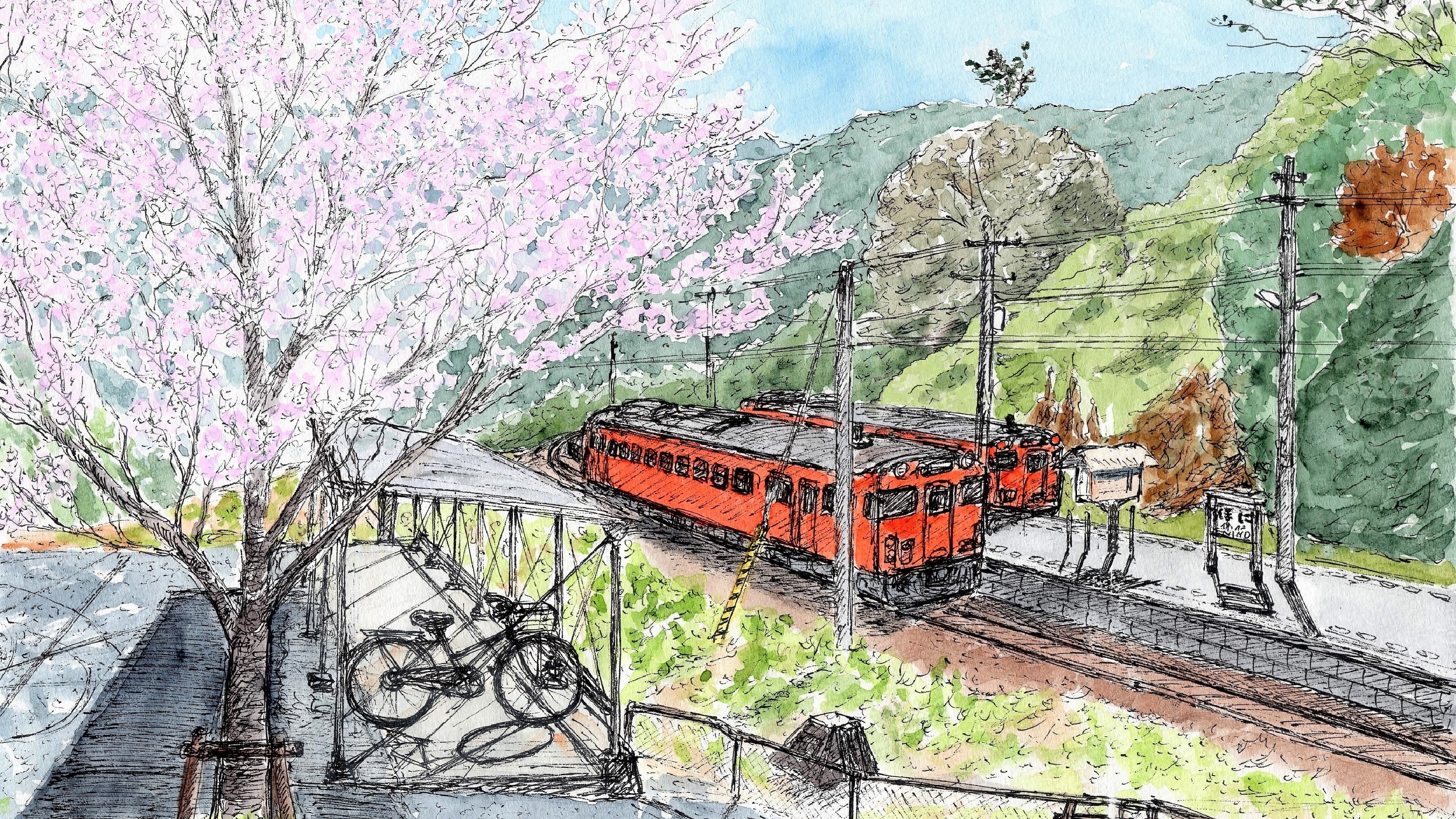

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

It was the first time for me to have tatami replaced. I’d moved often and tatami is always changed when moving into a new place, but I didn’t want to confess we hadn’t changed the mats in fifteen years, about double the normal lifetime. They could tell. They looked askance at the well-worn mats, but didn’t say anything. I felt embarrassed to have not done better with tatami care. Over the years, several of the mats had sunk. The top layer had shredded beneath a footrest, crumpled under a bookshelf, and worn thin beneath an office chair. I could slip a finger between a couple of the mats.

Bending to the mold, I suddenly felt very un-Japanese. I loved the tatami but hadn’t taken the right care of it. I realized that over the years, I’d not only been surrounded by culture, but I’d had the most Japanese of cultural objects right underfoot.

The parquet floor in the other rooms had always had pieces pop loose from time to time, another victim of humidity. But I keep good, strong glue and a weight to press them back into place. I’ve developed my own technique for the wood, but gluing pieces of the floor back in place could hardly compare to the tatami artisans.

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

Their workshop’s website said they’d done 36,000 installations. Even divided over two generations, it was an amazing number. You could see their experience in their practiced way or marking, planning, and handling the tatami. You could see their dedication in their faces when they complained that it was young Japanese who didn’t want tatami anymore. It was too much effort to clean and care for. No one wanted to roll out and roll up a futon every day. They wanted a mattress on a solid wood floor.

With the tatami gone, the house felt empty and hollow. My steps echoed eerily and with the support wood exposed, it was like staring into a dark basement, even though it’s less than a few fingers deep. The rooms looked emptier than I’d ever seen them. It was like the house had been broken in half. I cleaned up and waited, looking away.

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

The tatami specialists pulled up in front of our house in the late afternoon. I came out to greet them with the snow still coming down. They opened the back of the van and one by one hustled the dozen large mats back inside, sure-footed over the snow as they hauled the heavy mats out of the van and up the stairs.

The older of the three came inside to read the marks on the bottom of the mats and make sure they were going in the right place. On the bottom, they’d written notes with the secret to the puzzle. Directing the younger men to slip the mats into place, it took two of them to align the borders side by side and top to bottom. The mats fit snugly into their pre-determined place. And the house filled up with the rich, grassy aroma of tatami.

I thought they were done, but the younger two men started pulling up the mats one by one as the older master cut a slice of old tatami to slip under and level them out. He walked back and forth testing the balance in his socks, his feet as much a tool as his hands. Where it was off, he cut a slice of old tatami and slipped it below until all the mats and the heri borders lined up even more perfectly.

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

When he was finally satisfied, he invited me to step on the new mats. I took off my house slippers and stepped forward. The new green tatami gave back a nice crackle. The aroma welled up with each step. I knew that would fade, and the tatami color would gradually turn golden, the working of time itself part of the craftsmanship, but the fresh meadowy feeling of it was startling. Walking across the new tatami, the whispering crunch called out an invitation to drink a cup of tea, meditate, or do nothing. Tatami is more of a giant sofa than a floor.

As I walked back and forth over the new mats, I thought back to how much we’d used, and maybe abused, the tatami over the years. We hadn’t just walked or sat or slept on them. At home parties, students had spilled sangria and beer. Friends had dropped gravy and guacamole. I’d flopped down in the summer heat with only a towel between my sweaty back and the mats. At Christmas and New Year parties, we’d danced to funky music, jumping, twirling, and grinding the poor reeds underfoot. The tatami handled it all, but it could only do so much.

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

The first year I lived in Japan, I saw a row of women in a Kyoto temple bend over like a football scrimmage line with cloths in hand. At a signal, they scuttled forward, rubbing the cloths across the tatami while a massive gold Buddha looked down on their efforts. They worked back and forth in a steady line, cleaning the dust from the vast expanse of the hundred-some-mat interior. Wood often forms the pedestal for the Buddha, but it’s tatami that covers the sacred interior of most temples.

The largest tatami room in the world, with two thousand mats, is located in the hall of the True Pure Land Buddhist school, Shinrankai, in Toyama. I can’t imagine cleaning, much less replacing the tatami in a room that size. Our six mats couldn’t compare, but I felt the new mats brought something sacred to our house just the same. It smelled clean and soft, with a stately presence that flowed outward. The adjoining wood-floored rooms seemed like a frame around the central exhibit of the mats.

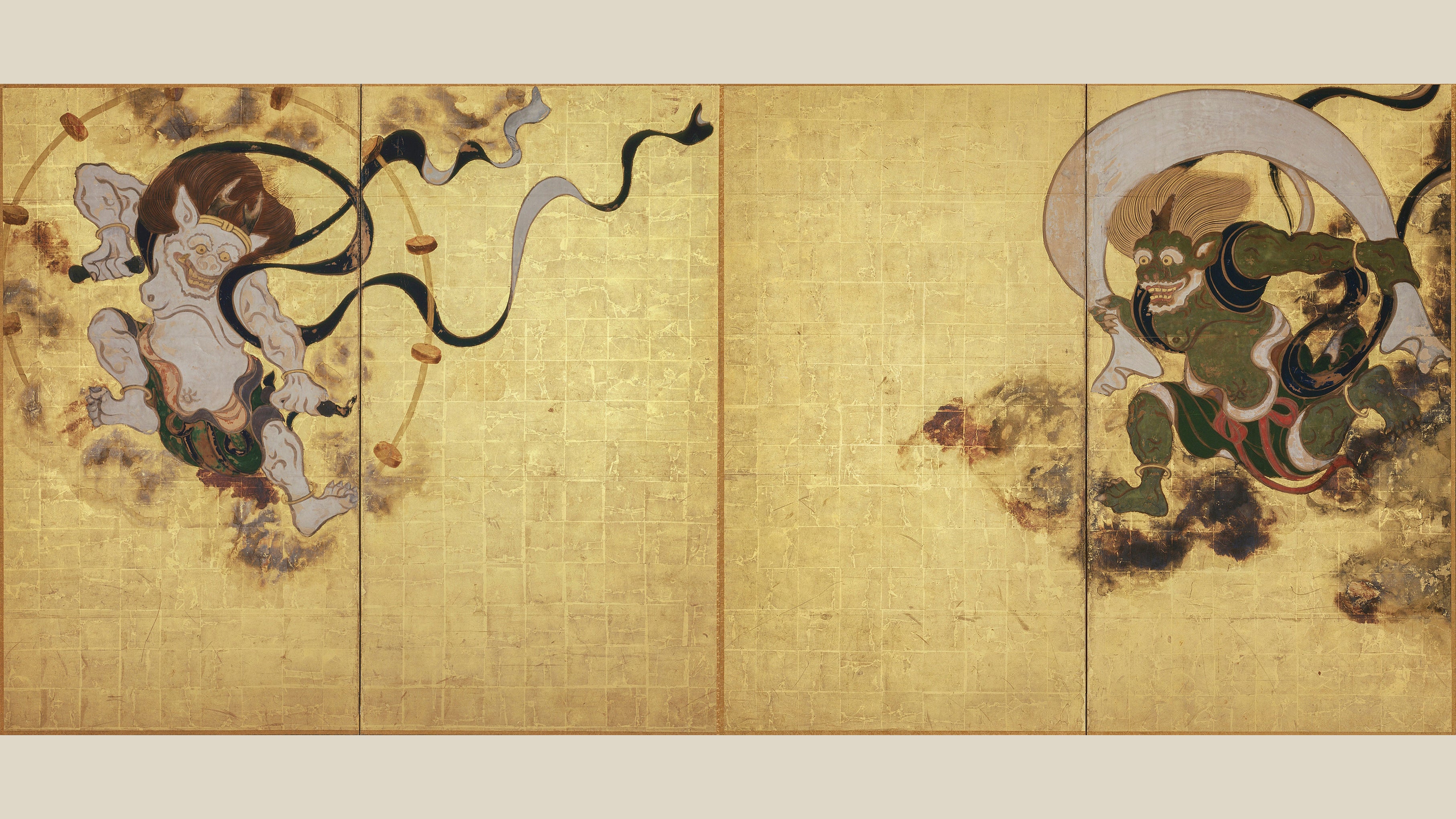

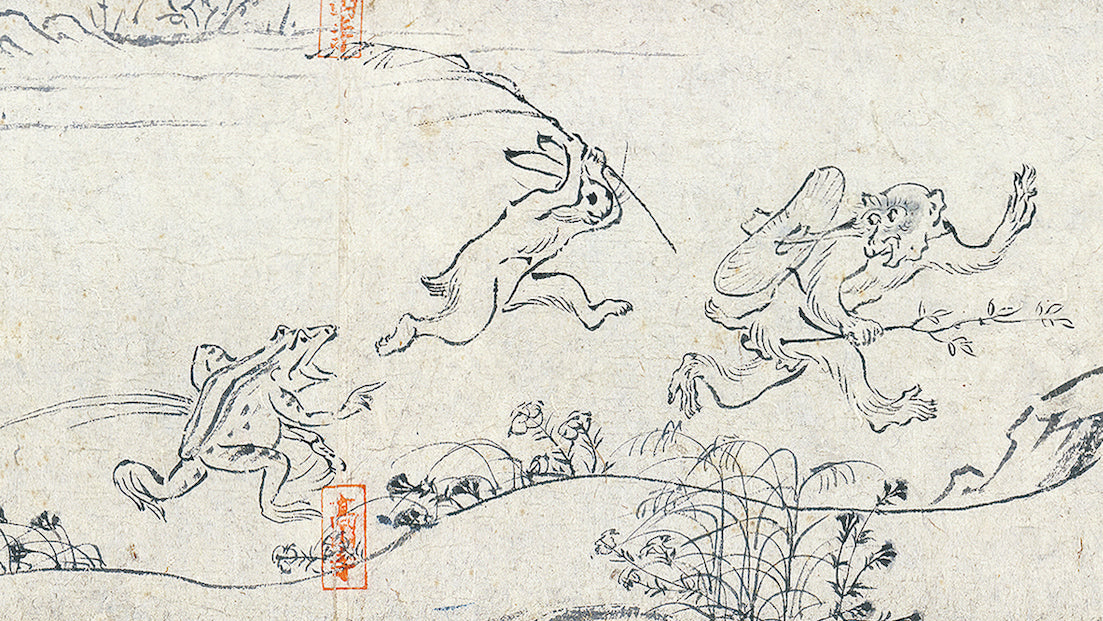

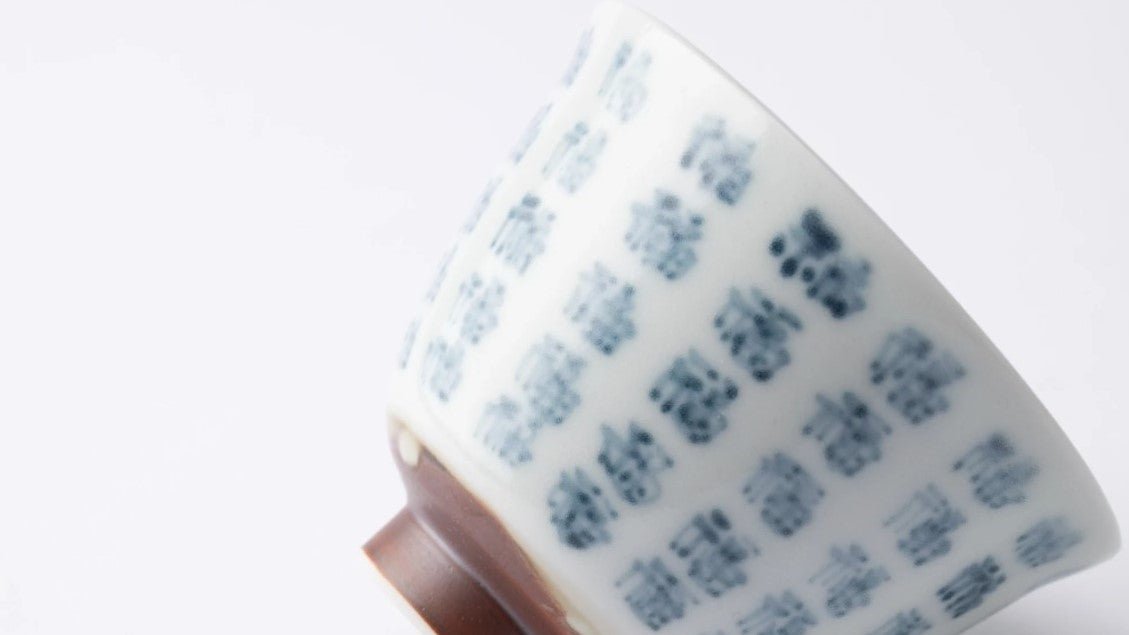

Image: ColBase (https://colbase.nich.go.jp/collection_items/tnm/A-69?locale=ja) / Modified from original

Tatami has a long history. In paintings of old Japan, the emperor always sits on the tatami while the lower-ranking aristocrats, statesmen, and feudal lords kneel on cushions set on wood. Since the eighth century, the nation’s politics were decided atop tatami. At the top of elaborate Girls’ Day Doll exhibits, the emperor and empress sit on—of course—a miniature block of tatami. Tatami reached the homes of commoners in the Edo Period (1603 CE–1868 CE). Having tatami at home elevates and ennobles one’s home.

Tatami is more than a floor. It’s bedding, a chair, a sofa, but it is also an expression of an entire set of aesthetic and cultural values. Japanese homes are often divided into washitsu, Japanese rooms, and yoshitsu, or western-style rooms. More and more, though, washitsu doesn’t fit big-city lifestyles. People no longer want—or need—a multi-functional space that can alternate between a living room, bedroom, dining room, or chill-out room. They want separate rooms for separate purposes without having to stoop over and dry-wipe reed mats.

In every culture, inside and outside are marked through conventions and customs, but in Japan, tatami is the inside of the inside. All Japanese visitors take their shoes off at the front door, but most also pause at the edge of a tatami room, leaving indoor sandals just outside the tatami. In that sense, the tatami craftsmen had restored the innermost sanctity of our house.

The above image is for illustrative purposes only.

The three tatami-makers swept up the last few loose bits of tatami they’d cut and rechecked the mats. Their eyes worked over our redone room. They’d brought to bear their experience, their craft, and a traditional set of values to transform our home and the life we lead there. It wasn’t just replacing a new set of tatami. It was re-establishing an entire cultural aesthetic. I followed their gaze as they made sure it was perfect and perfectly Japanese.

After satisfying themselves, the tatami craftsmen seemed to hesitate as they headed to the door. Could they trust me? They’d have to. They told me to call if there were any problems. But what problem could there be? Tatami wasn’t some machine or object that could break. It was a cultural artifact based on a complex set of beliefs installed in our home to dignify our life. I promised myself to take better care of it and learn its lessons.

After the tatami craftsmen drove off, I returned inside, walked to the tatami, wiggled my feet, enjoying the delicious crackle of the new reeds, and then dropped down and stretched out, sinking into the aroma of fresh tatami in what felt like a new home, a new attitude to life.