Understanding Japan’s National Treasures and Living National Treasures

De Ito Ryo

Among the pieces handled by MUSUBI KILN are several works created by artists designated as Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties: Yoshita Minori and Nakada Kazuo.

The title of Holder of an Important Intangible Cultural Property is perhaps better-known by its common name, Living National Treasure, and refers to "a living, human treasure of the country." This title refers to individuals or groups recognized by the state as possessing the highest level of skill in traditional performing arts such as Kabuki and Shamisen, or in craft techniques such as ceramics and lacquerware. These certifications are handled by the government, and Japan was one of the first countries in the world to evaluate these kinds of intangible traditional techniques as cultural heritage.

Separately, there also exists the designation of National Treasure, which the Japanese government applies to tangible works of fine arts, crafts, and architecture deemed to have extremely high historical or cultural value from a global perspective. The moniker "Living National Treasure" is actually a colloquial term created by the media based on this National Treasure designation.

Whether intangible or tangible, holding the title of National Treasure is proof that the Japanese government has officially recognized someone or something’s immense value, and it serves as a benchmark for judging the person or object’s artistic, historical, and cultural significance. In this sense, both "National Treasure" and "Living National Treasure" are essential keywords for deepening one's understanding of Japanese culture.

This article introduces the basics of National Treasures and Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties, along with interesting related trivia.

Table of contents

What Are Japan’s Largest and Smallest National Treasures?

As the name “Living National Treasure” is derived from “National Treasure,” to understand the former, one must first understand the latter. So let us begin with an overview of National Treasures.

The National Treasure designation is based on the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, enacted in 1950 to improve national culture through the protection and utilization of cultural properties. Among important tangible cultural properties, those of particularly high value and unparalleled significance are designated as treasures of the state and the people—National Treasures.

As of January 2026, there are a total of 1,149 National Treasures, including works of fine art, craft, and buildings. The Japanese prefecture with the highest number of designations is Tokyo with 293—more than Kyoto or Nara, which are famous for their many shrines and temples—due to the high concentration of museums and galleries in the capital.

Of all 1,149 items, the largest one is the Great Buddha of Todai-ji in Nara, coming in at 14.98 m (49.15 ft) in height. This Buddhist statue was constructed over the course of approximately nine years in the mid-eighth century by Emperor Shomu, who wished for national peace and the unification of the people's hearts.

The smallest National Treasure, on the other hand, is the King of Na Gold Seal (whose seal face is approximately 2.3 cm / 0.9 in across) housed in the Fukuoka City Museum. This gold seal is said to have been presented by a Chinese emperor to a local Japanese ruler in 57 CE. It was discovered during the Edo period (1603–1868 CE) in the eighteenth century on Shikanoshima Island in what is now eastern Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu—reportedly found by chance by a farmer doing agricultural work.

For National Treasures, where protection is a primary objective, appearance at exhibitions is generally limited to twice a year, with public display limited to sixty days. However, it is possible for items made of materials relatively resistant to deterioration, such as stone or metal, to have their displays extended beyond sixty days. Perhaps for this reason, the bronze Great Buddha of Todai-ji and the King of Na Gold Seal are National Treasures that can easily be appreciated within Japan by anyone at any time. Note that taking National Treasures out of the country is, as a general rule, prohibited.

Why the Silver Pavilion Is a National Treasure but the Golden Pavilion Is Not

Two representative Buddhist temples in Kyoto, Rokuon-ji and Jisho-ji, are known for the structures popularly called the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji) and Silver Pavilion (Ginkaku-ji), respectively. While both are iconic Japanese buildings widely known at home and abroad, the Golden Pavilion is not a National Treasure, whereas the Silver Pavilion is. Why is this?

The Golden Pavilion originated as a mountain villa built by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, which ruled Japan during the medieval Muromachi period (1336–1573 CE). It earned the name "Golden Pavilion" for the lavish decoration of its pillars and walls with gold leaf. Although completed in 1397, it was destroyed by arson in 1950 by a young monk training at Rokuon-ji; it was rebuilt five years later. Because the current Golden Pavilion is, in a sense, a “modern” building, it is not designated as a National Treasure.

The Silver Pavilion, meanwhile, is a two-story structure said to have been influenced by the Golden Pavilion, and it was built within the villa of the eighth Muromachi shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa. The style of its architecture and that of the surrounding gardens are praised as representative of the culture of that era. It is said there was a plan to cover the building in silver leaf at the time of its construction, but ultimately, only lacquer was applied to the interior and exterior walls of the second floor, built to enshrine the Buddha. From the seventeenth-century Edo period onward, it came to be called the Silver Pavilion in contrast to the Golden Pavilion. Unlike the Golden Pavilion, it retains its original appearance from the time of completion, a value that was eventually recognized and led to its designation as a National Treasure in 1951.

The Artist with the Most Individual National Treasure Designations, the Medieval Painter Sesshu

Watada Minoru, who oversees cultural property surveys at the Agency for Cultural Affairs—the government office involved in National Treasure designations—describes National Treasures as "objects that would not be embarrassing to take anywhere in the world to represent Japanese culture” and (in the case of art) “things that are indispensable for explaining specific characteristics of a particular era of Japanese art."

The ink wash paintings, or suibokuga, by Sesshu (1420–1506?), a Zen monk of the Muromachi period, fit these requirements perfectly. He holds the record for most works created by a single individual that have been designated as National Treasures.

Sesshu was the first Japanese ink-wash painter to travel to China, the birthplace of the technique, to refine his skills. There, he was not only praised as a painter but also recognized as an excellent Zen monk before returning to Japan about two years later. While based on Chinese ink wash styles, his unique works—which he thoroughly understood and perfected—are characterized by a rugged dynamism while maintaining an overall sense of profound stability and composure.

As the number of his designated National Treasures suggests, Sesshu is regarded as the most important and preeminent painter in Japanese art history. Fukushi Yuya, who researches early modern painting at the Kyoto National Museum, states that this status is the result of the cumulative evaluation of many subsequent generations of painters.

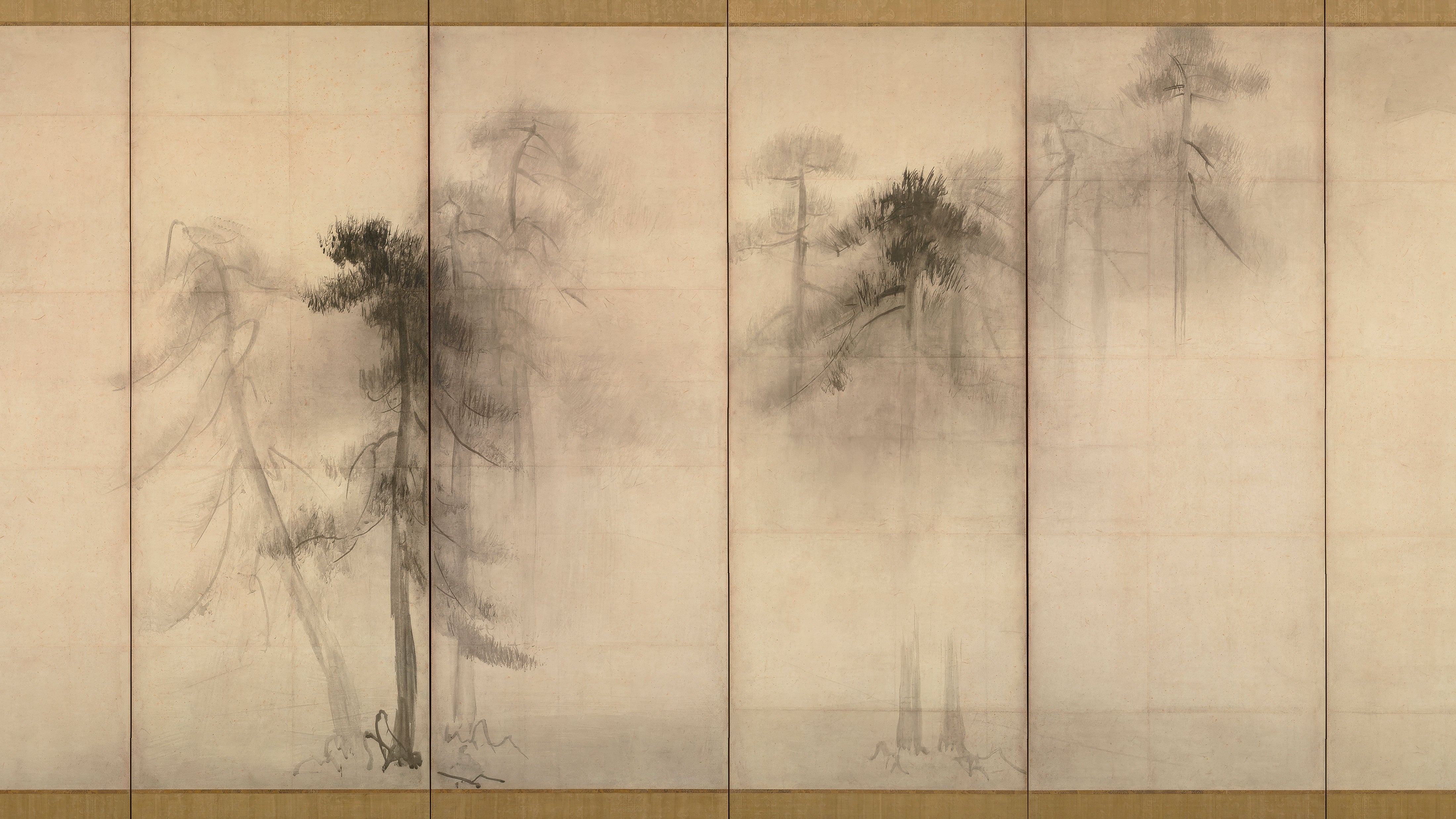

Claiming to be Sesshu’s successor was Hasegawa Tohaku (1539–1610), who painted the National Treasure folding screens Pine Trees (Shorin-zu byobu)—considered one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of Japanese ink wash painting. Also influenced by Sesshu was the Kano school, the largest group of painters active in Edo-period Japan, who studied and actively absorbed Sesshu's work. Furthermore, Kano Tan-yu (1602–1674), who served as the highest-ranking official painter for the Edo shogunate and reigned at the pinnacle of the art world at the time, was particularly dedicated to studying Sesshu’s style, exerting a strong influence on Edo-period painting in general. Many other important Japanese painters fall under Sesshu’s influence as well, including Ogata Korin (1658–1716), known for his brilliant and decorative style; Sakai Hoitsu (1761–1828), who belonged to the Rimpa school following Korin's lineage; and Ito Jakuchu (1716–1800), famous for his creative paintings of flora and fauna. This influence now extends overseas and is known to have provided creative inspiration to Korean-born, world-renowned contemporary artist Lee Ufan.

A Strange Fact? Only Two of the Eight National Treasure Matcha Bowls Are Japanese-Made

There are a total of eight tea bowls made for drinking matcha during the tea ceremony that are designated as National Treasures. Of these, five are imports made in China around the twelve to thirteenth centuries, and one is an import made on the Korean Peninsula in the sixteenth century. There are only two Japanese-made tea bowls designated as National Treasures, and both were produced later, in the second half of the sixteenth century or thereafter.

The fact that imports account for the majority of National Treasure matcha bowls—treasures of Japan—might seem contradictory at first glance. However, that perception changes if one knows the history of matcha bowls in the Japanese tea ceremony.

The tea ceremony was born from the development of matcha-drinking, a custom that was introduced from China between the late twelfth and early fourteenth centuries. Because of this, the tools used, including the matcha bowls, were initially imports from China. These were called karamono, or Chinese wares, and were generally characterized by a brilliant appearance. The karamono tea bowls designated as National Treasures are all highly decorative and continue to strongly influence Japanese ceramics today: the Yohen Tenmoku Chawan, with blue spots shining against a black background; the Yuteki Tenmoku (Oil Spot) Chawan, where countless spots and luster on the interior and exterior resemble oil floating on water; and the Taihi Tenmoku (Tortoiseshell Glaze) Chawan, featuring a mottled pattern on its exterior that resembles a sea turtle's shell.

These luxurious karamono tea bowls were particularly prized by the samurai class, and using them to drink matcha became a symbol of status. Tea gatherings—where a host entertained guests with matcha—were also events for participants to enjoy the beauty of karamono. In this way, karamono tea bowls played a major role in the establishment of tea ceremony culture. Furthermore, it is said that at that time, products imitating karamono were actively made in central Honshu’s Seto and Mino regions, representative ceramic-producing areas of Japan.

By the late fifteenth century, the tea ceremony began to spread beyond the samurai class into the daily lives of people. Along with this came the birth of wabi-cha, a new form of tea ceremony that found beauty in simplicity rather than luxury. Highly valued in wabi-cha were tea bowls called wamono (Japanese wares), which, in contrast to karamono, utilized the simple texture of clay. Also valued were koraimono (Korean wares), which were created not as luxury goods, but as everyday utilitarian vessels in various parts of the Korean Peninsula. The two Japanese-made tea bowls designated as National Treasures—the Shino Chawan and the Raku Chawan—are none other than wamono, while the remaining imported bowl, the Oido Chawan, is koraimono. Among Japan-made wamono matcha bowls, those fired in the Mino region, in particular, exerted a great influence on other ceramic production areas in Japan, as did the koraimono bowls—fostering diverse styles across the country.

The tea ceremony is an important aspect of Japanese culture that has significantly influenced traditional Japanese architecture, art, and cuisine—and matcha bowls are among the items that accurately trace a path from the tea ceremony's birth to its development and evolution. Given this context and the history of ceramics in Japan, the fact that many once-imported tea bowls are designated as National Treasures can be considered entirely reasonable.

The System Preventing the Loss of Advanced Skills

To review, the title of Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties is proof that the state has recognized an individual as possessing the highest level of advanced skill in traditional performing arts or craft techniques.

This system was institutionalized for "skills at the highest level that might go extinct if nothing is done, with the aim that while the holders are still alive these skills may be protected and passed down to future generations." Individual designees are paid 2 million yen annually as a subsidy for refining their skills and training successors.

Due to budgetary reasons, the number of individual designees was capped at 116. However, it has been decided that starting in 2026, up to 10 more will be added. In addition to the existing fields of performing arts and crafts, the scope will expand to include the "culture of daily life," including toji (sake brewers), chefs of the Kyoto cuisine (Kyo-ryori) nurtured over Kyoto’s long history, Japanese tea-manufacturing artisans, ikebana artists, and calligraphers.

As can be understood from the system’s originating purpose, a designation of Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property automatically expires upon an individual's death. Although the aforementioned ink wash painter Sesshu is a prominent figure with the highest level of evaluation in Japanese art history and is invariably included in history textbooks, he—as a deceased person—will absolutely never become a “Living National Treasure.”

Works by Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties Available at MUSUBI KILN

Among MUSUBI KILN’s pieces are some made by Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties. Namely, these are works by Yoshita Minori and Nakada Kazuo, ceramic artists of Kutani ware, one of Japan’s representative ceramic styles.

Born in 1932, Yoshita is a leading figure in the yuri-kinsai (underglaze gold leaf) technique. This involves applying patterns made from cut gold leaf onto the surface of a vessel that has been colored with pigment, then covering the entire piece with a glossy, colorless transparent glaze before firing. The elegant, soft beauty created by delicate gold leaf motifs of flowers and birds against deep background colors is the charm of his yuri-kinsai.

Meanwhile, Nakada, born in 1949, is the creator and sole holder of the yuri-ginsai (underglaze silver leaf) technique. He uses silver leaf, which in contrast to the brilliance of gold has a clean and refined impression, to create patterns on the vessel’s surface, then applies a pale-colored or colorless transparent glaze of his own formulation before firing. The way various patterns, which seem to sink beneath the surface, are viewed through the glaze creates a unique and unparalleled beauty.

As “succession of skills” is one of the major goals of the system of Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties, the designated individuals themselves are required to have a track record and a willingness to guide and train successors. However, the superior skills and expressive power of both Yoshita and Nakada are one-of-a-kind; even if successors are born in the future, it is unlikely that works identical to theirs will be created. We hope our readers will take this opportunity to see for themselves what works by Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties are truly like.

In Japan, a 2025 movie titled Kokuho, meaning “National Treasure,” became an unprecedented hit. Set in the traditional theater world of Kabuki, it depicts the turbulent life of a man who, despite not coming from a multi-generational family of Kabuki actors like most, enters the world by chance, gradually distinguishes himself, and ultimately rises to become a Living National Treasure. The film is scheduled to begin screening in the United States in February 2026 and has reportedly already been released sequentially in various Asian and European countries.

This work is perfect introductory material for learning more about what a Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property is. It is also an ideal film for learning about onnagata—a unique aspect of Kabuki where male actors use various techniques to brilliantly perform female roles.

For those who are interested, I highly recommend watching the movie Kokuho along with viewing the works of Yoshita Minori and Nakada Kazuo. Through them, you will surely be able to sense the profound appeal of Japanese culture.

Dejar un comentario

Este sitio está protegido por hCaptcha y se aplican la Política de privacidad de hCaptcha y los Términos del servicio.