26 August 2024

Glass from the Past: A Visit to the Hirota Glass Japanese Glass Museum

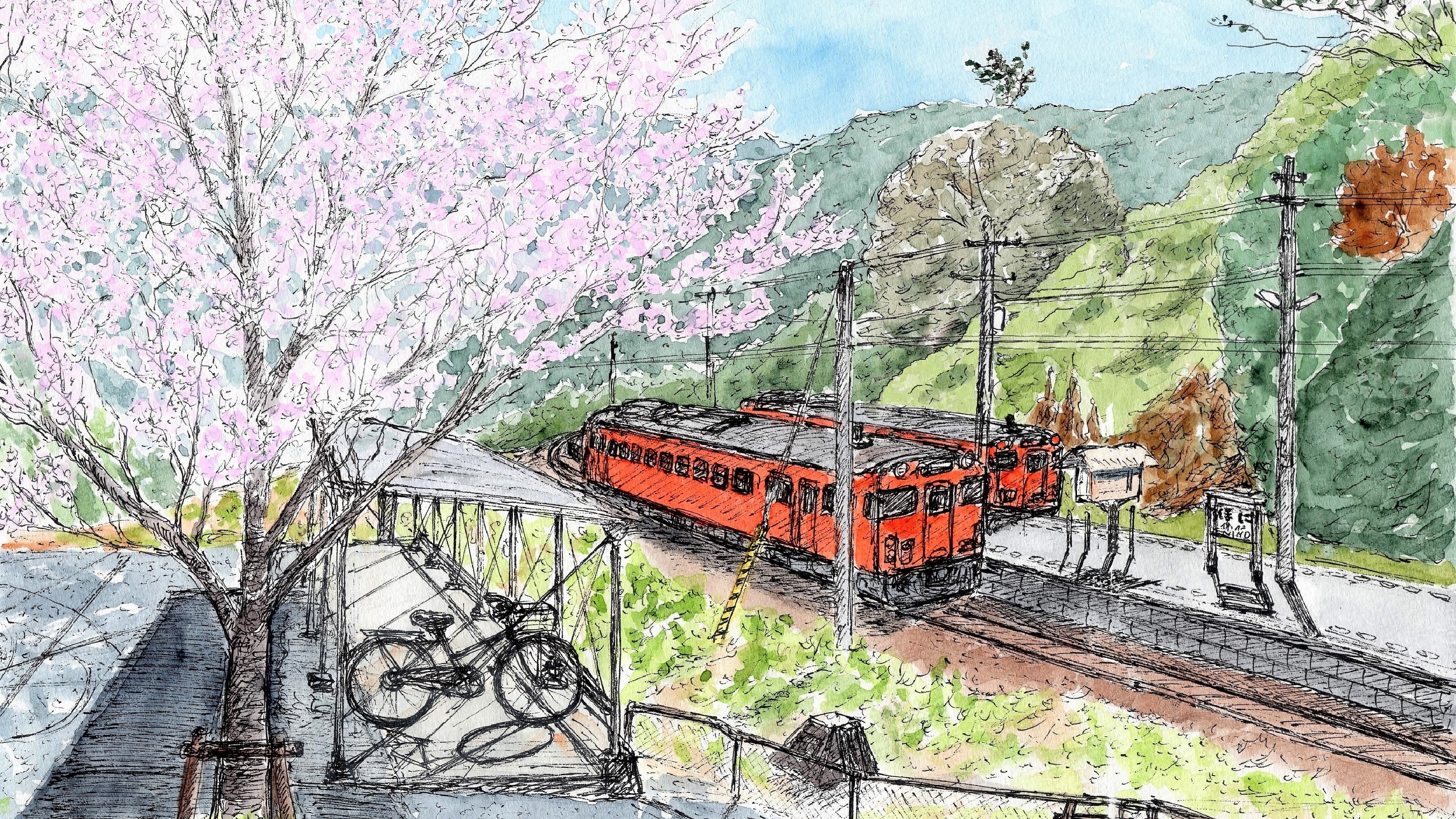

In a quiet neighborhood not far from the popular destination of Tokyo Skytree, just a few minutes outside Kinshicho Station in Sumida Ward, sits a vast collection of Japanese glass. It is the Hirota Glass Japanese Glass Museum. Owned and operated by Hirota Glass, this place serves as not only a fantastical display of the vintage designs Hirota has reimagined for modern tables, but also showcases the real vintage designs, gathered throughout the years, that inspire their creations.

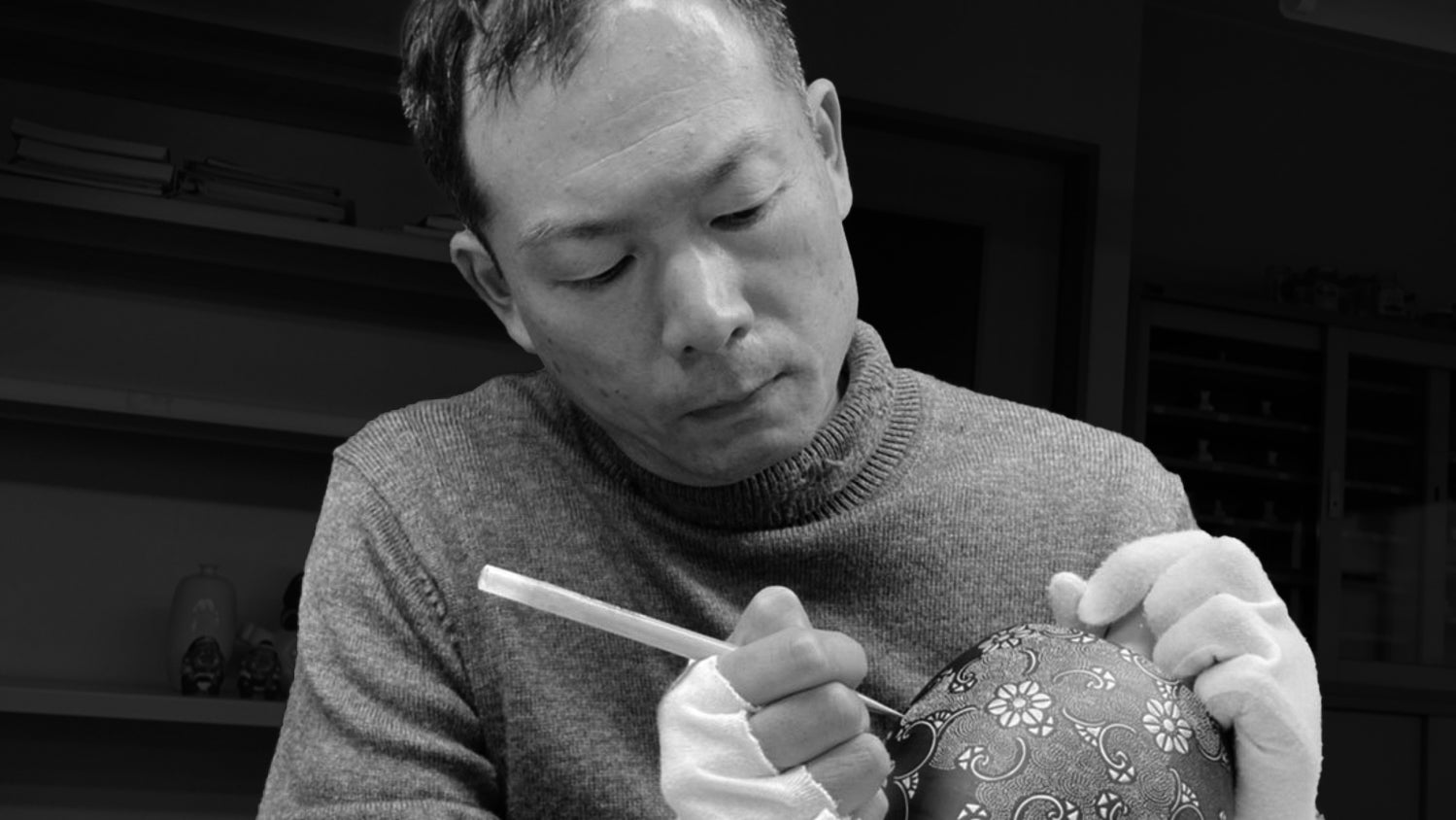

On a hot summer's day in July, we paid a visit to the museum to meet with current President Hirota Tatsuaki and learn more about how Japanese glassware has changed throughout the years—and what is still beloved today.

Contents

- Through the Hirota Looking Glass

- A Walk through Hirota History

- Exit through the Gift Shop

Through the Hirota Looking Glass

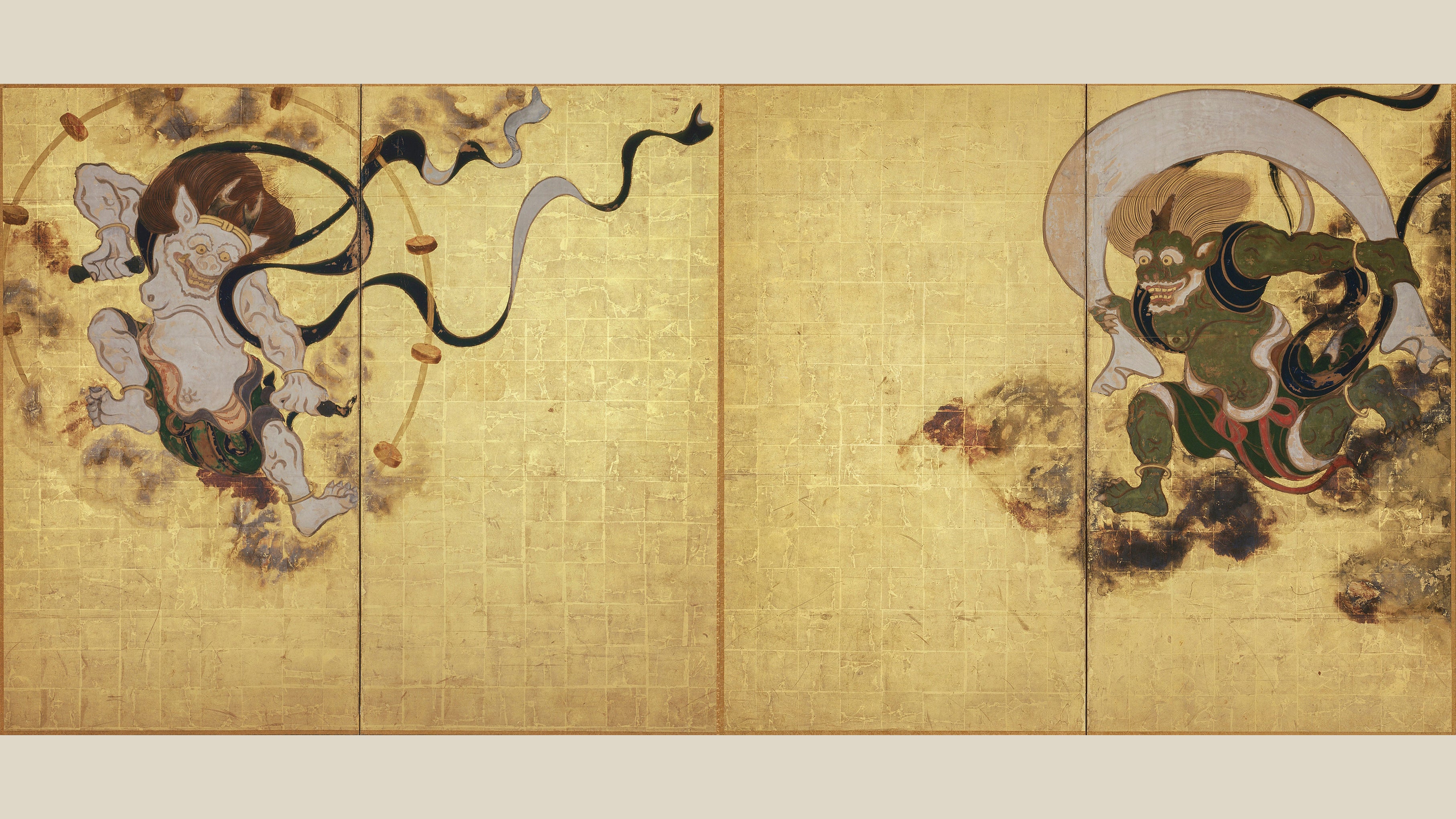

The history of glass spans centuries, experiencing important milestones during many cultural periods. According to the Hirota Glass timeline, the story starts back in 1549 when a missionary introduced Western glass to Japan. 52 years later, in 1601 during the Edo period (1603 CE–1868 CE), glassblowing efforts began domestically and two centuries later, Kagaya Kyubei essentially transformed Japanese glass with the innovation of cut-glass art, now known as Edo Kiriko.

Skipping ahead to 1899, during the Meiji era (1868 CE–1912 CE), the first-generation owner, Hirota Kinta, founded Hirota Glass. In 1914, during the Taisho era (1912 CE–1926 CE), the Koto Glass Factory opened and began manufacturing cups, which would then lead to branded glasses in 1921, made in collaboration with drinks companies including Calpis (makers of Calpico), Kirin Beer, and more.

Unfortunately, disaster would strike just two years later: the Great Kanto Earthquake. The factory was forced to close soon after, in 1926, then re-opened the next year in the current location.

Three generations later, after Kinta, Eijiro, and his father Tatsuo contributed to the changing landscape of the Japanese glass industry, Hirota Tatsuaki stepped up as the fourth-generation company president in 2007. In 2017, the company opened the museum to give visitors insight into the past and present of Hirota Glass.

When asked why Hirota Glass set up shop in Sumida Ward, President Hirota said, “In the past, places like Asakusa and Nihonbashi in Tokyo were where people gathered. Among the various manufacturing industries, the glass industry was a latecomer. So that people would quickly get to know and use glass products, it was better to start the business in a densely populated area. That’s why we established our company in Sumida.”

It was in the Taisho era that Hirota Glass found its footing in the glass industry, and right on time. President Hirota told us it’s been just over 100 years since glass became a part of Japanese daily life. “Originally, glass was used as shades for oil lamps, and later it started being used as tableware.”

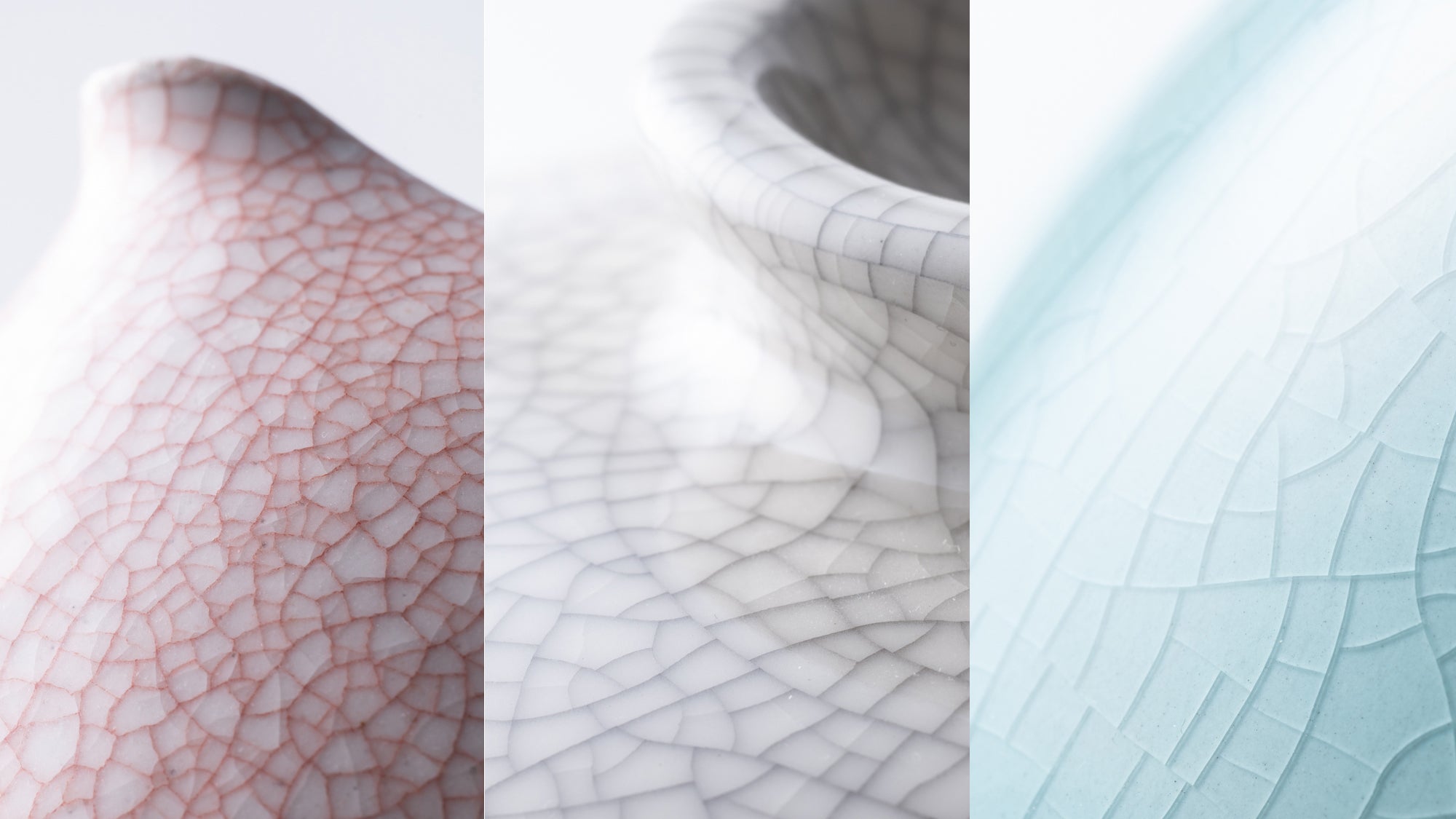

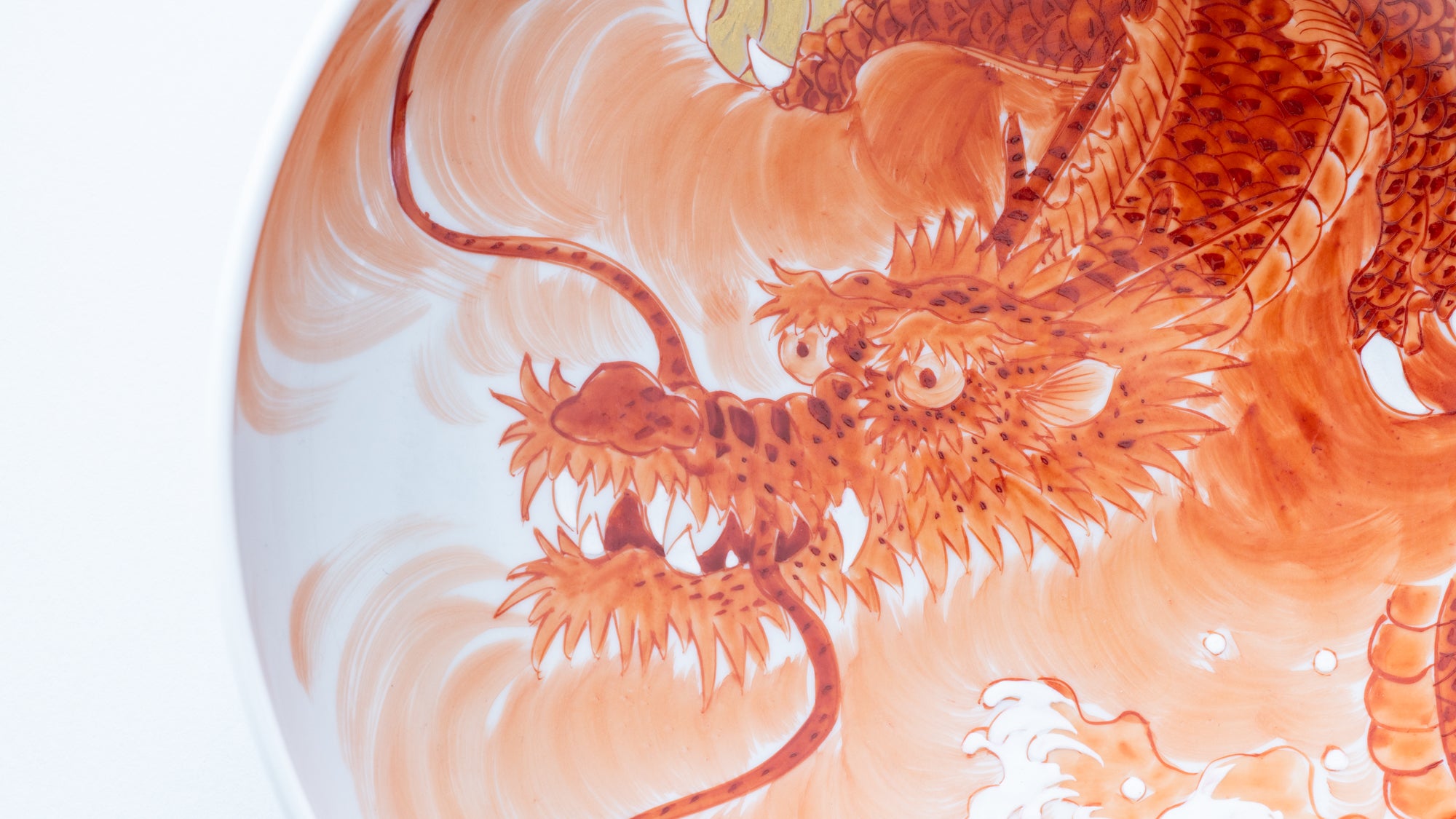

The importance of this era can be seen throughout the collections that Hirota Glass makes today, especially in the Taisho Roman series. “During the Taisho era, the number of glassmakers increased. They made things like shaved ice bowls and milky white ice cups.”

But despite the company’s history in making these pieces, bringing back the technique proved harder than expected. “We realized that it was not easy to revive just by referring to books. We needed the knowledge of experienced craftsmen who had actually made it. There are subtle nuances that only craftsmen understand.”

“We knew the materials needed for the aburidashi technique but didn't know how to manufacture it. The third-generation president found craftsmen who were involved in this technique at the time and asked them about it. Between 1970 and 1980, Hirota Glass successfully revived this lost technique. The process is almost the same. The design is almost the same.”

A Walk through Hirota History

After our illuminating chat, President Hirota brought us upstairs to see the glasses and glass-related items they’ve collected throughout the years. Some pieces were delightful, some were confusing, but all provided insight into the changes made to use and design throughout the years. Some vintage glasses would not be out of place in a modern home today, proving that as much as things change, things stay the same, too.

Hirota graciously walked us through the collection, answering questions we had about the pieces on display, showcasing a grand knowledge of the industry. A large paper showed a catalog of pieces available for purchase in the Edo period, and included glass bottles and tubes. He explained, “One major influence on the glass industry in Japan was the adoption of Western medicine. Western medicine required glass to store.” Another example of its importance in storage was the extremely large glass jar that greeted us when leaving the elevator. President Hirota explained that it would have been used in something like a general store, able to hold a great amount of product at once. All I could think about was the arm strength a craftsperson must need to be able to blow such an enormous glass object.

At one point, I spotted a label on one of the pieces that said BYRON in all caps. I asked if it comes from Australia, and the president explained that the Byron label has been part of their branding since the 1960s, both on domestic pieces and those shipped overseas. The result is that although Hirota Glass is Hirota Glass in Japan, overseas the name Byron has become synonymous with the company.

In addition to the glass pieces displayed in cabinets, there were lampshades in use and the machine that helped shape them. A medieval-looking mold, with sharp teeth in a circle, would be used to create a frilly shape on the bottom of a rounded lampshade. Seeing the contrast between the fierce angles of the machine and the delicate frills it created was astounding.

Checking every display, I realized that although glass is such a commonplace item in our lives, it’s not at all mundane. Even the windows that graced the museum were Edo Kiriko-style, reminiscent of the beautiful stained glass pieces that hung in my grandma’s kitchen, making the sunlight dance in a dazzling array of colors on every surface the beams reached.

Pieces have a unique purpose, like the collaboration done with Kirin in the 1970s. Made for a tasting, red tumblers are numbered, 1 through 7 to denote which beer the person was trying. A relatively simple idea, yet when set in glass, made truly remarkable. One of the glasses also showed the challenge in making colored glass—its red hue was not quite the same as the others, because it is hard bringing a true red hue to life in the material, President Hirota told us.

There were also miniatures, impossibly tiny versions of the company’s real-life collection. These delighted me in particular, because why! Who had this idea? It struck me as a work made by a designer who had a sense of humor; maybe someone whose child wanted doll-sized versions of the pieces. Unfortunately, the card next to them said they were incredibly difficult to ship without breaking, and they weren’t made very long.

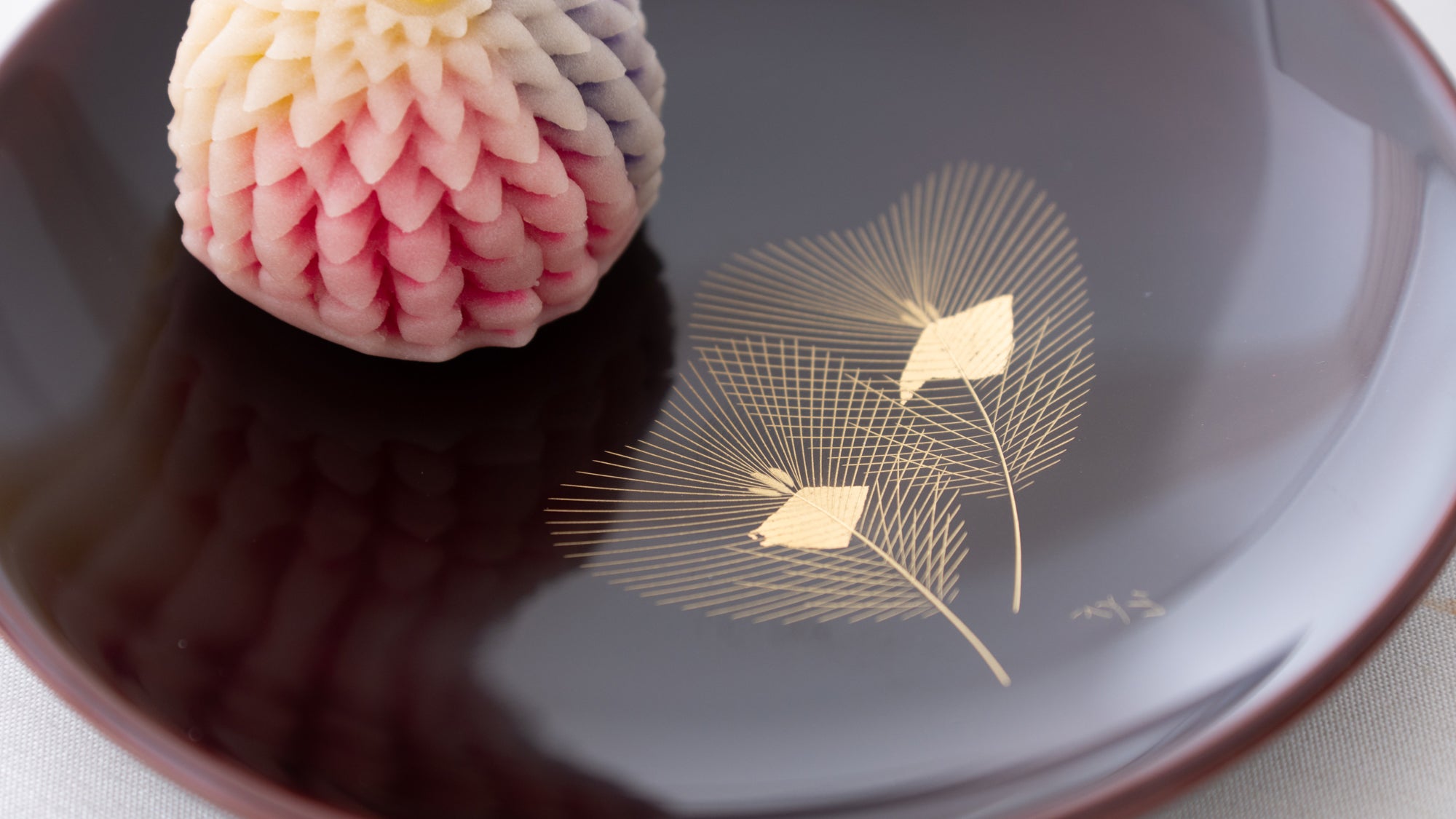

There was so much to see, including vintage catalogs and even woodblock stamps that were created to stamp the visuals of pieces in catalogs back in the 1950s. But a highlight was when President Hirota allowed us to peek at one of the books in the library, an encyclopedia of vintage glass called “Depression Glass.” While interviewing him I mentioned that I collect milk glass, the opaque, white pieces that became popular in the US in the early 20th century. Something I especially like in milk glass is called the hobnail pattern, very similar to the texture of the Arare series produced by Hirota Glass. President Hirota flipped open the book to show me a page portraying a beautiful piece of hobnail milk glass, not unlike one of my favorite pieces in my personal collection.

Yet another example of this material, so often taken for granted, doing something unexpected. Glass truly does bring us all together, bridging generations and cultures alike.

Exit through the Gift Shop

Of course, no visit to a museum is complete without a stop in the gift shop. The shop here is unique because it is essentially a retail store dedicated to the pieces produced by Hirota Glass, but it was nevertheless fun to explore and see how the century-old collection has inspired the current selection. On the way down to the first floor, our cameraman, Akashi, spotted a poster hung in the elevator—a recreation of one of their mid-20th-century catalogs stamped with the woodblocks we’d just seen in the musuem. President Hirota said, “People enjoyed that poster, so we’ve reprinted it for people to buy.”

And sure enough, there it hung on the wall of the gift shop. Under its vintage flair, we were able to peruse many different pieces, from their striking Edo Kiriko glasses, colorful and hand-cut, to the Arare bowls, just begging to hold kakigori shaved ice, and the Taisho Roman pieces, whose unique aburidashi technique adds elegance to the surface that simply isn’t done justice in photos.

After exploring the history of the company and of the glass industry itself, seeing the result of many years of dedication and passion collected in one storefront felt heavy. Especially as President Hirota said, “Unfortunately, it's an industry in decline… Designs are mostly created in-house. But many designs have been exhausted.”

From windows to lightbulbs, bottles to cups, glass is an integral part of our daily lives. It allows us to see beauty with clarity—but Hirota Glass has perfected the art of transparent materials that enhance the view, too. Every piece produced throughout the company's history seems to be made with a singular purpose: to turn traditional techniques into something timeless, to be enjoyed for centuries to come.

Sometimes, to innovate you have to look to the past. And Hirota Glass is learning from their history to make the most of their present, and hopefully, head into a long future.