The Art of Clay and Fire

Hagi Ware

Hagi ware is a traditional Japanese pottery produced mainly in Hagi City, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Known for its soft, earthy appearance and subtle textures, it is valued for the way it reveals the natural character of the locally-sourced clay. The slightly porous body retains warmth and absorbs a trace of the liquids it holds, gradually shaping the vessel’s surface and tone through years of use.

Beloved by generations of tea masters, Hagi ware has long been celebrated alongside Raku and Karatsu in the saying, “First Raku, second Hagi, third Karatsu.” Its quiet, unpretentious beauty continues to inspire both practitioners of the tea ceremony and admirers of Japanese ceramics worldwide.

Hagi ware dates back over 400 years, having been produced in the official kiln of the Mōri clan during the early Edo period (1603–1868 CE). Korean potter brothers Ri Shyakko and Ri Kei came to Hagi and established a kiln in the Matsumoto district east of Hagi Castle. Their work, inspired by Korean-style tea bowls highly valued in the tea culture of the time, laid the foundation for the Hagi ware tradition.

In the years that followed, artisans such as first-generation Saeki Hanroku and first-generation Miwa Kyusetsu contributed to the refinement of techniques and the expansion of production.

After the Meiji Restoration, with the end of domain patronage, production shifted to private and corporate kilns. By the Taisho period (1912–1926 CE), Hagi ware had regained its prestige as a favored tea ceramic. Following World War II, individual artists became more active, and the tenth- and eleventh-generation Miwa Kyusetsu—Miwa Kyuwa and Miwa Jusetsu—were recognized as Living National Treasures in 1970 and 1983, respectively.

In 1957, Hagi ware was designated a Selected Intangible Cultural Property, and in 2002, was designated a Nationally Recognized Traditional Craft of Japan, securing its place as one of the country’s most celebrated ceramic traditions.

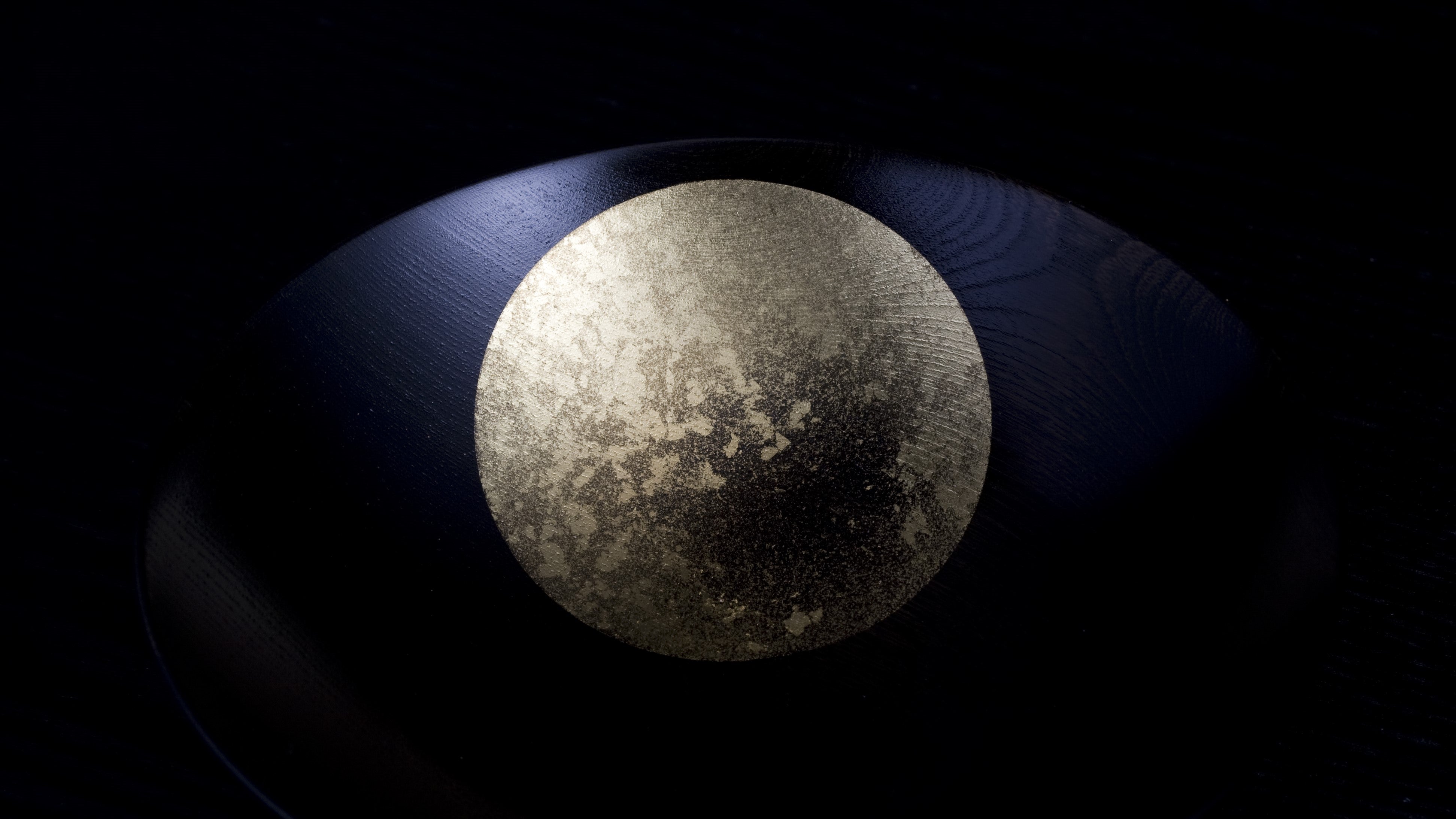

Hagi ware is celebrated for a well-known change called Hagi no nanabake—the “seven transformations”—in which the appearance of a piece gradually changes with years of use. Tea or other liquids seep through the fine crackle patterns, known as kannyu, formed by the differing shrinkage rates of clay and glaze, deepening the color from within and giving each vessel its own distinctive character.

Made from loosely compacted clay with little vitrification, Hagi ware has a soft texture and is highly absorbent, with the ability to retain warmth and moisture. Over time, these qualities allow the surface to develop a patina of color and texture that reflects the aesthetics of wabi sabi.

Hagi ware favors a clay-focused style with little painted decoration. Its character emerges from the blend of clays, the way the glaze is applied, tool marks such as spatula or brush patterns, and the random effects of the flame during firing. These subtle elements combine to create its unique appeal.

The distinctive feel of Hagi ware begins with its clay, a key element in achieving its characteristic tsuchiaji, or the distinctive character of the clay, valued by tea practitioners. Traditionally, three natural clays, Daido, Mishima, and Mitake, form the foundation of Hagi ware. Each has its own properties, and artisans combine them in as needed to create a clay body (taido) suited to each piece.

Daido Clay

The primary clay for Hagi ware, grayish-white and rich in sand and gravel, with relatively low iron content. Highly plastic and firing to a softly finished body, it gives Hagi ware much of its fundamental texture and character.

Mishima Clay

A reddish-black, iron-rich clay that adds variation in texture and color when blended into the body. It is also used for slip decoration and glaze formulation, and is indispensable for expanding the expressive possibilities of Hagi ware.

Mitake Clay

A kaolin-rich white clay with a fine sandy texture, mixed with Daido clay to reduce plasticity and improve resistance to high firing temperatures.

Filters