Aizu Lacquerware

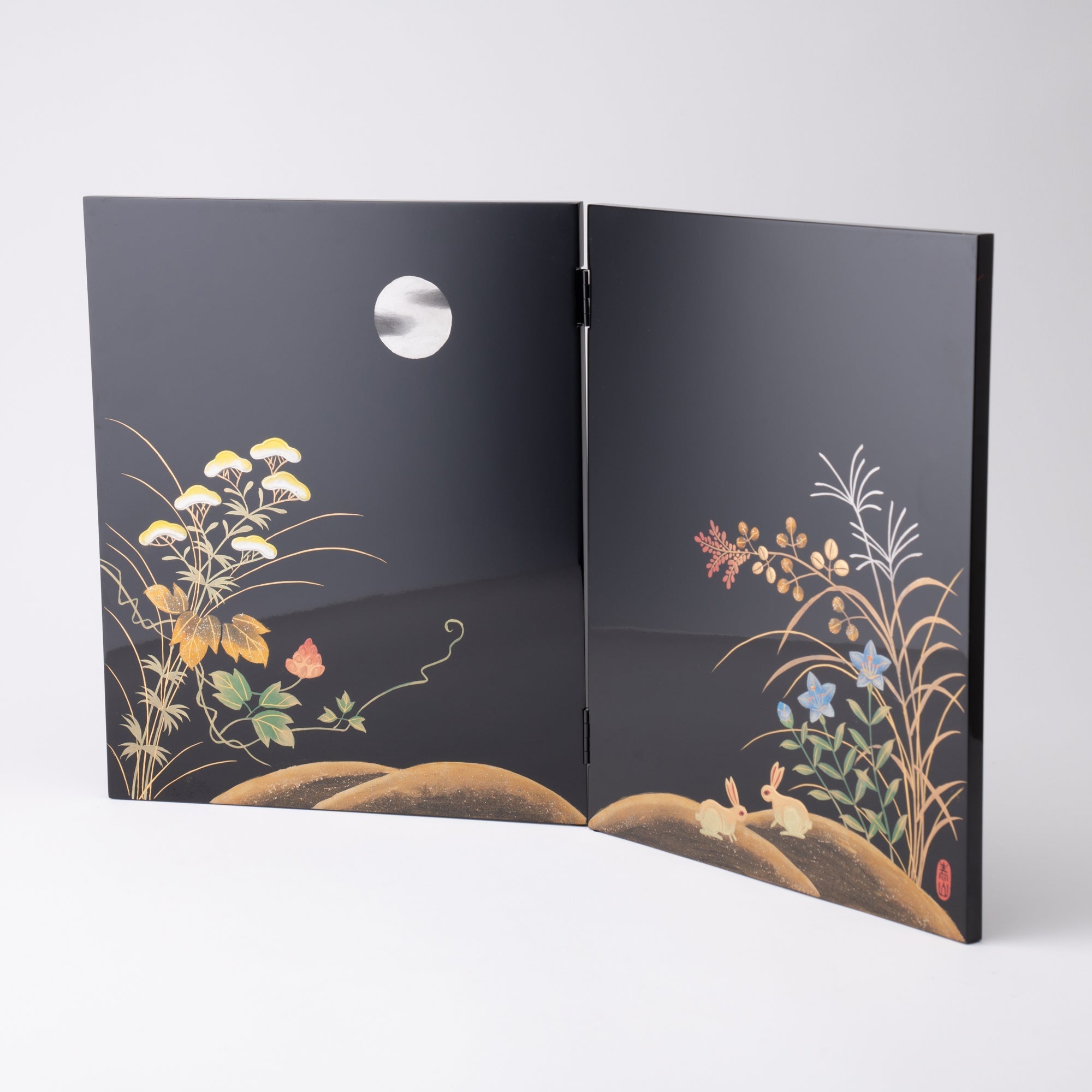

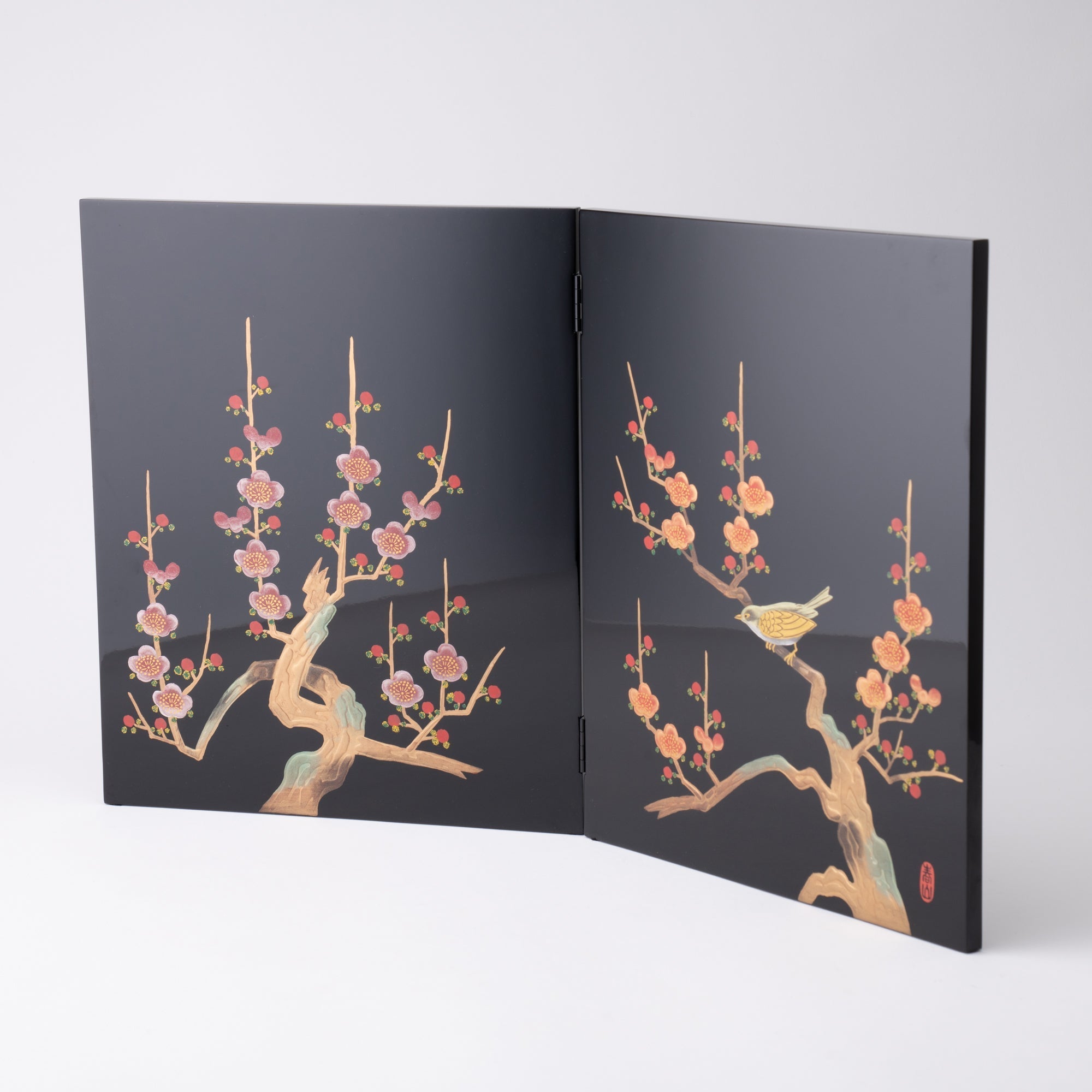

Aizu lacquerware is a traditional craft originating from the Aizu region in western Fukushima. Nestled in a basin surrounded by mountain ranges, the region's humid climate provides ideal conditions for working with lacquer. Aizu lacquerware is known for its auspicious motifs and refined decorative techniques, including Aizu-e, featuring vibrant Japanese floral patterns, and maki-e, which uses gold powder to create intricate designs.

Firmly rooted in over 400 years of tradition, Aizu lacquerware continues to evolve by embracing modern techniques, sharing its timeless beauty with the world today.

The history of Aizu lacquerware dates back to the Muromachi period (1336–1573 CE), when a powerful local clan promoted the cultivation of lacquer trees in the region. In 1590, Gamo Ujisato became the lord of Aizu and invited skilled artisans—including lacquerers, woodworkers, and maki-e artists—from his native Omi Province (now Shiga Prefecture), encouraging the development of lacquerware as a local industry.

In the 18th century, decorative techniques such as maki-e were introduced from Kyoto, and Aizu lacquerware grew in popularity, eventually being exported to countries such as China and the Netherlands. Although the industry suffered major damage during the Boshin War in 1868, it recovered in the late 19th century and reestablished itself as one of Japan’s leading lacquerware production centers.

With a history spanning over 400 years, Aizu lacquerware continues to be handed down through generations and remains a symbol of enduring craftsmanship.

Hana-nuri uses a type of lacquer called yūyu-urushi, which is lacquer blended with drying oil. This mixture enhances the gloss and improves workability. However, applying the lacquer evenly with a brush is extremely difficult and requires advanced skills from experienced artisans. The coating process consists of three layers: the base coat, the middle coat, and the top coat.

Urushi-e is a technique where colored lacquer (iro-urushi) is applied directly with a brush to create decorative patterns. Colored lacquer is made by mixing pigments such as red, yellow, or blue. Due to the natural properties of lacquer, the available colors are somewhat limited, typically resulting in calm, subdued tones like black, red, yellow, green, and brown. The signature Aizu-e combines auspicious elements such as pine, bamboo, plum blossoms, and decorative arrows.

Chinkin involves carving patterns into a lacquered surface using a special blade called a chinkin-to. Gold leaf, silver leaf, or finely ground gold powder is then embedded into the carved grooves. After the excess metal is removed from the non-carved areas, the design remains inlaid in the surface. Since Aizu chinkin uses shallower carving than in other regions, it results in a softer, more delicate impression.

Maki-e is a decorative technique in which a design is painted with lacquer, then sprinkled with gold or colored powder, using the lacquer as an adhesive. Among the various types of maki-e, Aizu lacquerware is particularly known for keshifun maki-e. In this method, the design is drawn with a brush heavily loaded with lacquer, and then, while carefully monitoring the drying process, the finest gold powder (keshifun) is gently applied using cotton wadding. This results in a soft, matte finish with elegant subtlety.

Production Process

Making the Wooden Base

Traditional lacquerware begins with the careful preparation of a wooden base, followed by the application of lacquer and decorative techniques. The trees used as raw materials are cultivated for decades or even centuries. After being felled, the timber is dried for several more years, sometimes decades, to reach optimal quality. Skilled woodworkers determine the ideal timing to use the wood, bringing out its best qualities in each piece they create.

Coating

The role of the lacquerer is to apply layers of lacquer to the shaped wooden base, giving it a smooth, refined texture as a vessel while also enhancing its durability. Lacquer hardens through a chemical reaction in which urushiol, one of its main components, binds with moisture in the air. By carefully refining the lacquer and applying it in multiple layers—from the base coat to the final finish—a warm and distinctive texture is created.

This process requires a deep understanding of the properties of lacquer. Because it is highly sensitive to dust and airborne particles, the humidity must be meticulously controlled throughout. As a result, the workspace is kept in strict isolation, and even family members are rarely allowed to enter during the coating process.

Maki-e Decoration

In this traditional decorative technique, a pattern or image is drawn onto the lacquered surface with a fine brush. While the lacquer is still wet, gold or silver powder is gently sprinkled over the design. Once dry, the pattern is revealed in shimmering detail. Maki-e takes advantage of lacquer’s natural adhesiveness, allowing even the finest lines to be rendered with precision and grace. A final thin layer of lacquer is then applied and polished, completing the exquisite maki-e decoration.

Makers

Related posts

Filters