Kyo Ware & Kiyomizu Ware

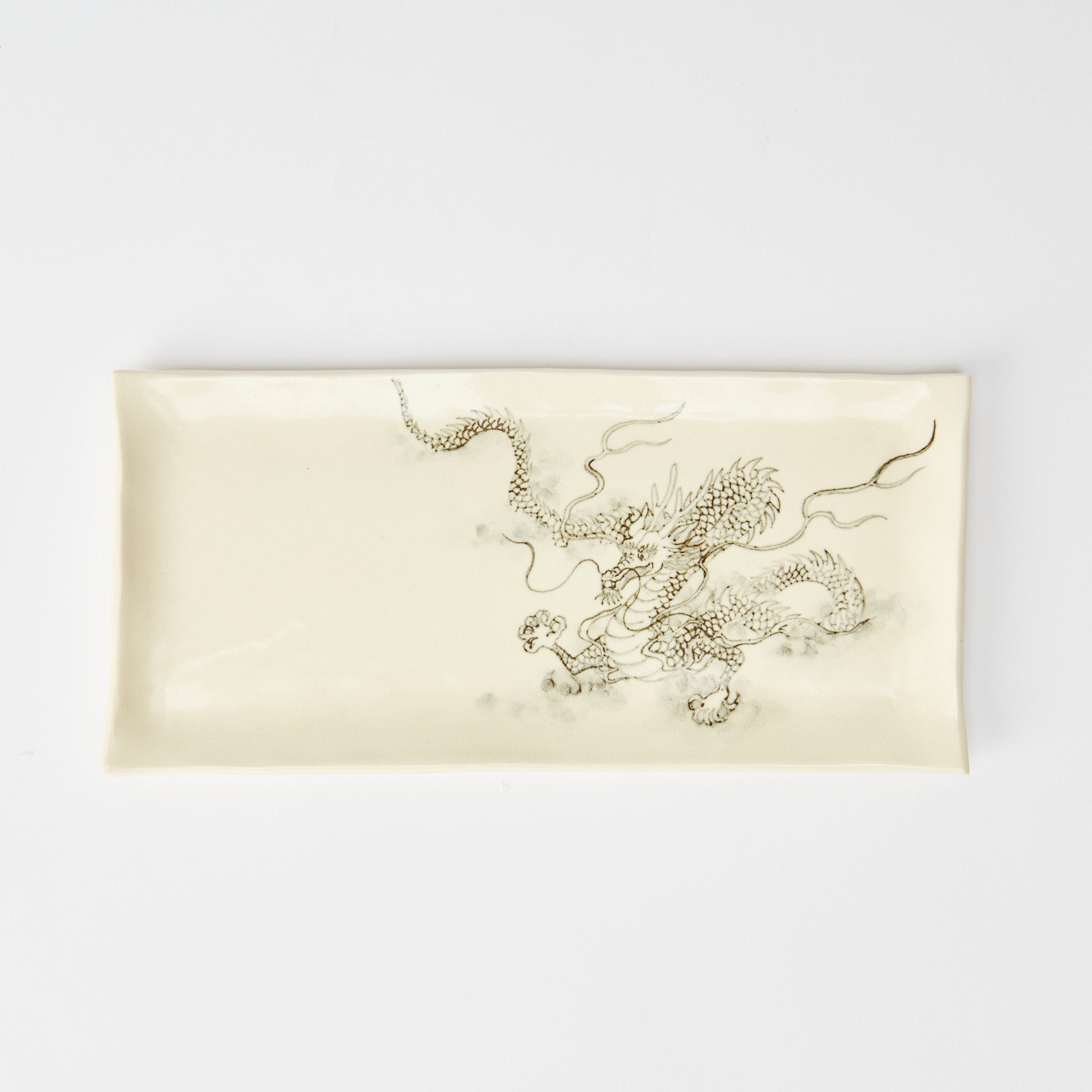

Kyo ware and Kiyomizu ware, collectively known as Kyo-yaki and Kiyomizu-yaki, are celebrated pottery styles from Kyoto. Known for their vibrant designs, finely sculpted forms, and dedication to handcrafted detail, these wares reflect Kyoto’s distinctive sense of beauty and artistic refinement.

Defined by a long-cultivated diversity, Kyo ware and Kiyomizu ware have drawn on techniques and styles from pottery traditions across Japan, evolving into a richly expressive and distinctly Kyoto art form. Recognized as a Traditional Craft of Japan in 1977, they continue to be cherished for their cultural depth and everyday appeal.

Kyoto, Japan's historic capital, has witnessed a rich history, beautifully reflected in the evolving styles of Kyo ware and Kiyomizu ware. These ceramics range from ornate designs to simpler, rustic pieces, each carrying a quiet warmth and presence that invites a sense of connection with every use.

Known for their exquisite design and functionality, these ceramics embody seasonal motifs and auspicious symbols, blending practicality with elegance. Each piece reflects the unique personality of its creator. As a result, it is cherished as a symbol of Kyoto’s enduring artistic legacy and is prized for its historical significance and exceptional craftsmanship.

During Kyoto’s time as Japan’s capital, tea masters and court nobility favored pottery that broke from prevailing styles, preferring distinctive shapes and colors. This demand led to the creation of specialized workshops producing unique pieces for ceremonial use. The meticulous craftsmanship involved means production has always been limited, making Kyo ware and Kiyomizu ware both rare and highly prized.

Not defined by a single style, Kyo ware and Kiyomizu ware stand out for their stylistic diversity. Each artisan blends various forming methods, such as handbuilding, wheel throwing, and slip casting, alongside decorative techniques like sometsuke and overglaze enamel painting. Despite this variety, all pieces share refined elegance and superb craftsmanship, uniting them in a cohesive artistry.

Pottery production in Kyoto advanced significantly during the late Momoyama and early Edo periods (late 16th to 17th centuries), particularly with the introduction of noborigama (climbing kilns) in areas like Awataguchi. During the Edo period (1603–1868 CE), Kyoto’s pottery further flourished as tea wares became highly sought-after by tea masters, court nobles, and feudal lords. Nonomura Ninsei, active around 1647, became known for his elegant overglaze enamel designs, while his disciple Ogata Kenzan later collaborated with his brother, Ogata Korin, to create Rimpa-style dishes that helped define a distinct Kyoto aesthetic.

By the late Edo period, potters such as Okuda Eisen and Aoki Mokubei emerged, advancing the craft through both innovation and the revival of classic styles. Eisen is credited with successfully firing porcelain in Kyoto for the first time. During the Meiji period (1868–1912 CE), Kyoto’s pottery industry faced challenges following the relocation of the capital to Tokyo, but artists and merchants turned to exports and technical innovation. In the Taisho era (1912–1926 CE), the industry expanded to surrounding areas, and despite the rise of mass production elsewhere, Kyoto’s workshops continued to produce handcrafted tea utensils. These small-scale studios helped preserve the region’s artisanal legacy through a period of great transformation.

Related posts

Filters