Dazzling beauty, a pivotal figure in Japanese aesthetics

Kanazawa Gold Leaf

Renowned for its radiant, refined luster, Kanazawa gold leaf is crafted in and around Kanazawa City in Ishikawa Prefecture. Today, accounting for 100% of Japan’s gold leaf production, it remains at the heart of the nation’s cultural heritage.

This exceptional material has been used for centuries in Japan’s most treasured landmarks, including the iconic Nikko Toshogu Shrine. Beyond architecture, it enriches traditional crafts such as lacquerware, Buddhist ritual objects, textiles, and Kutani ware.

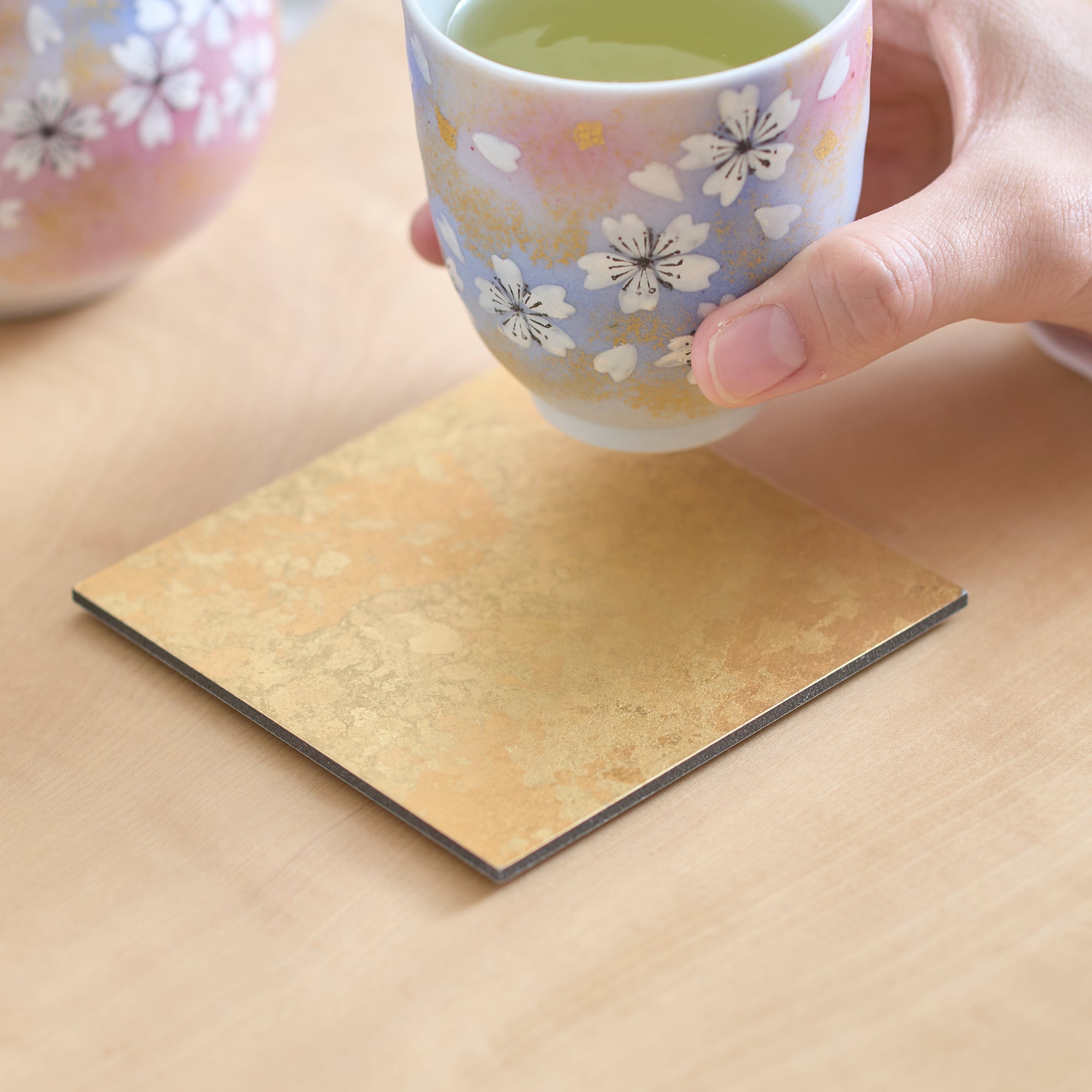

More than decoration, Kanazawa gold leaf embodies a uniquely Japanese aesthetic—one that cherishes the timeless beauty and brilliance of gold.

Kanazawa gold leaf is more than a material. It has established itself as one of the traditional crafts representing the craft kingdom of Kanazawa.

For centuries, Kanazawa gold leaf has long been treasured in Japan’s most celebrated cultural sites. From the Shibi (bird's tail-shaped roof ornaments) of Todaiji’s Great Buddha Hall to the golden folding screens of the Shosoin, it has shaped the beauty of temple architecture and sacred art. Beyond historic landmarks, gold leaf continues to enrich traditional crafts such as Kyoto’s Nishijin Ori brocade and Ishikawa’s Wajima lacquerware. Today, its use has expanded into everyday life, from gold leaf ice cream and skincare to nail art, while also inspiring new expressions in interior design.

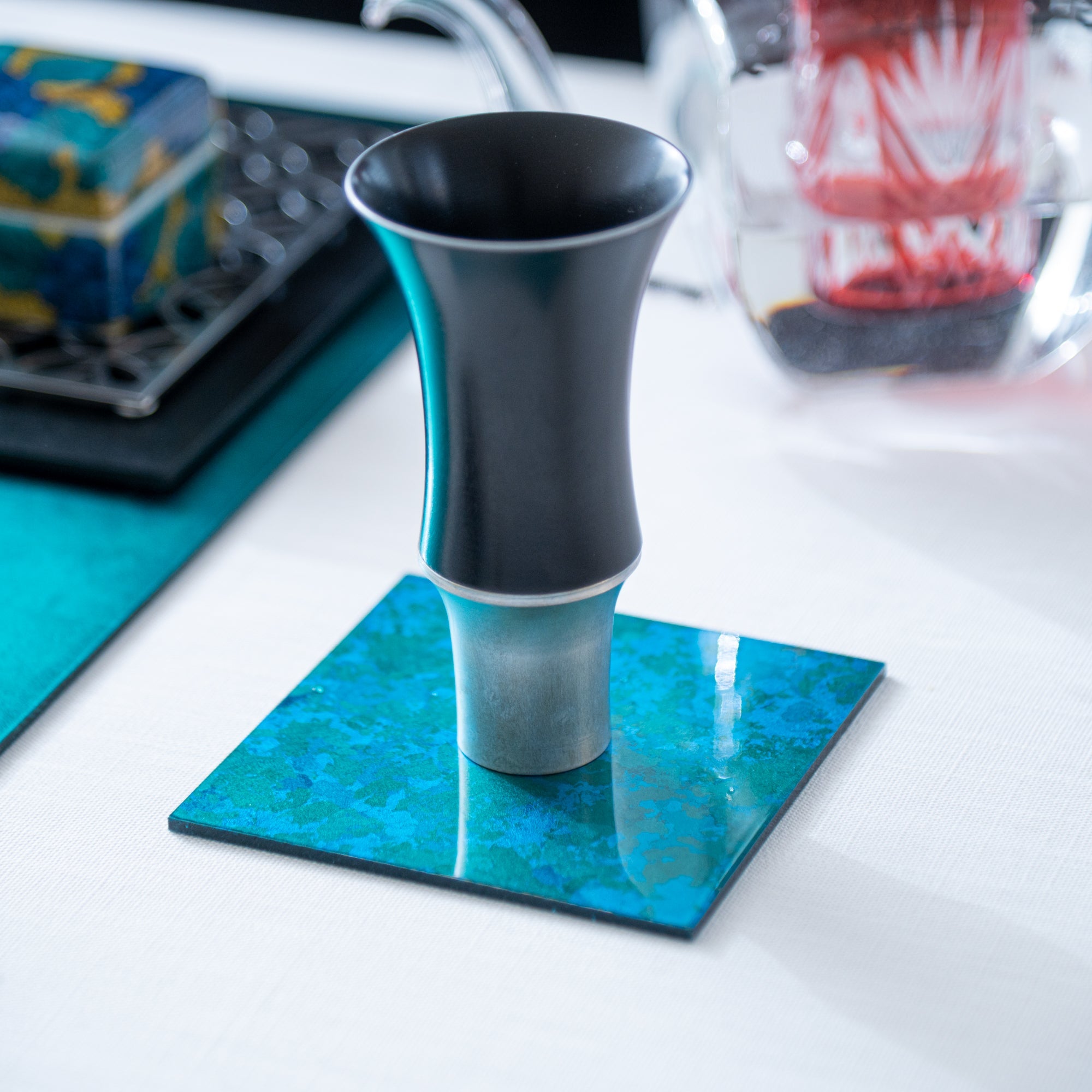

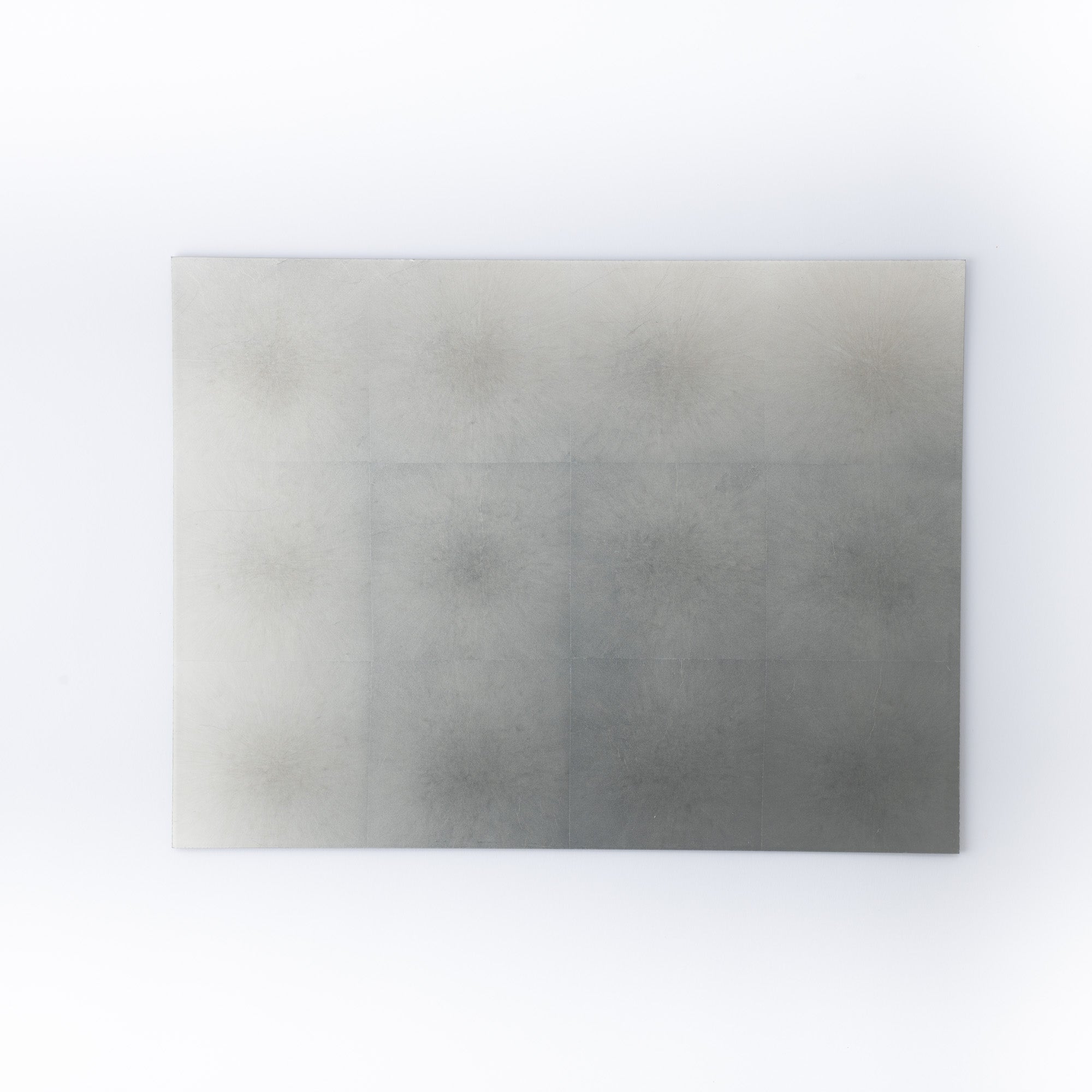

It refers not only to gold, but also to silver, tin, brass, and other metal foils. Each type reveals the character of the metal itself, while subtle variations in composition, special treatments, and application techniques offer limitless creative possibilities. As it continues to enrich Japan’s traditional crafts, Kanazawa gold leaf is also shaping a new chapter in its history.

It is said that gold leaf was first produced in Kanazawa in 1593, when Lord Maeda Toshiie, the founder of the Kaga domain, received an order from Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the Korean War.In 1808, the burning down of the Ninomaru Palace at Kanazawa Castle was the catalyst for the establishment of the foil industry in Kanazawa. Although a large amount of gold leaf was needed for the revival of the industry, the shogunate at the time placed only Edo foil under the protection of the shogunate, and prohibited the production of other types of foil. As a result, the Kaga clan is believed to have kept foil production alive in hidden workshops, ensuring the craft’s techniques would survive for generations to come.

In 1864, only the official foil of the domain was allowed to be made into foil, and Kanazawa foil made great progress. Furthermore, with the disappearance of Edo foil in the Meiji era (1868-1912 CE), Kanazawa foil could be produced and sold throughout the country as a market. During World War I, Kanazawa foil was mechanized to meet global demand. During World War II, the foil manufacturing industry was temporarily destroyed by restrictions on the use of metals, but production resumed during postwar reconstruction and the uses of gold leaf expanded.

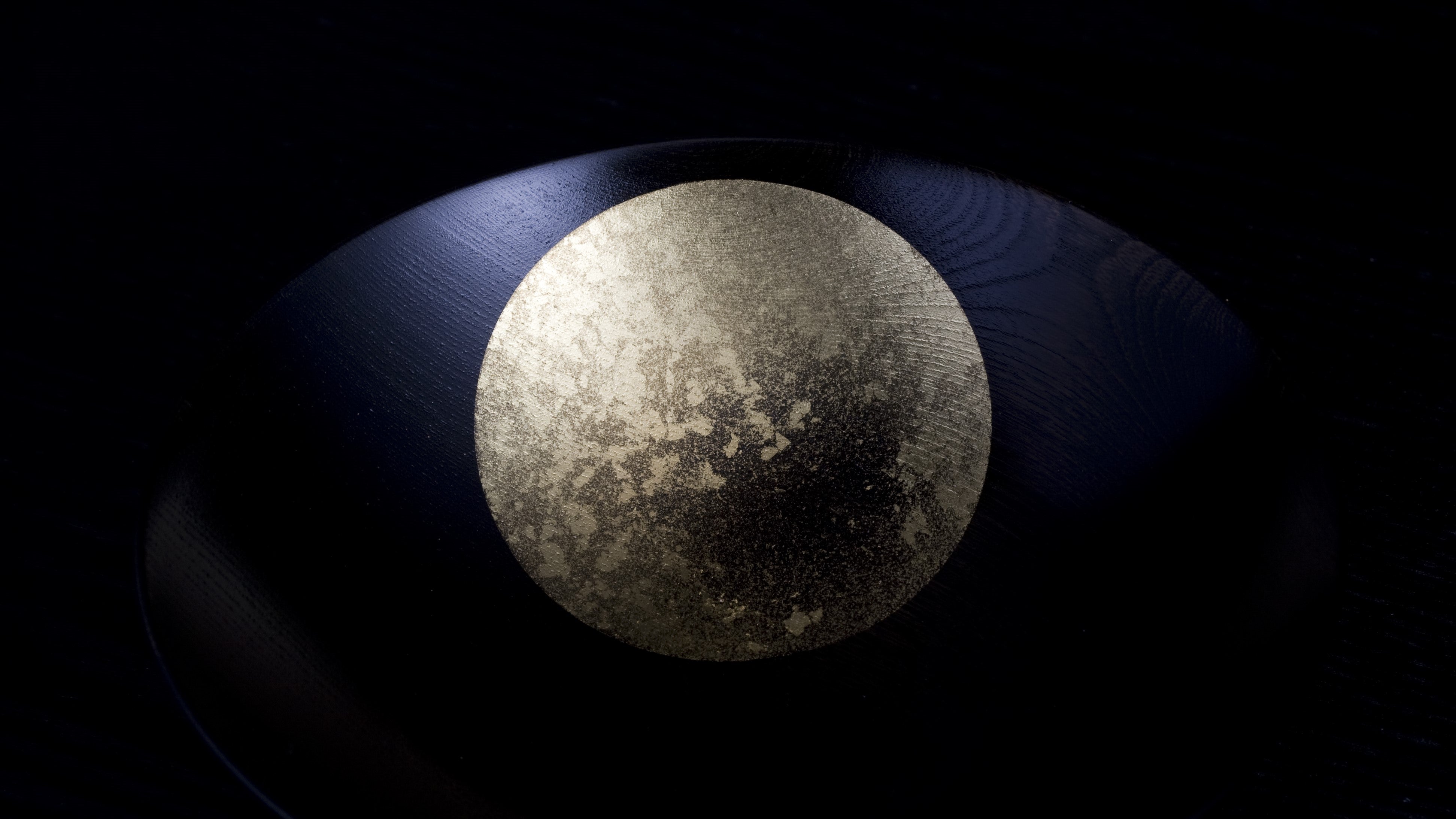

Gold leaf is only about one ten-thousandth of a millimeter thick—so thin that just 2 g (0.07 oz) of gold can be beaten out to cover an area the size of a tatami mat. Many factors must align to produce such an ultra-thin leaf: exceptional craftsmanship, specialized paper that determines the quality of the finished product, favorable climate conditions, and more.

1. Gold alloy

Silver and copper are added because pure gold is too soft to be hammered into leaf. The mixture is heated in a hearth bowl to about 1300℃ (2372℉) and stirred with a carbon rod. After 10–15 minutes, once fully melted, it is poured into molds to solidify.

2. Rolling out

The gold alloy is rolled out with a rolling mill into a belt-like strip called nobe. This process is repeated about 20 times until the strip is only 0.02–0.03 mm thick. It is then cut into 6 cm (2.4 in) squares, known as koppe.

3. Preliminary Pounding

The koppe squares are hammered into thin sheets, matching the size of the leaf-making paper. At 12 cm (4.7 in), the gold is called aragane. These sheets are quartered and beaten into 20 cm (7.9 in) squares, known as koju. The koju sheets are then cut into quarters again and pounded further to form oju. When the oju sheets are placed between finishing paper, they are called uwazumi. At this stage, the gold is about 0.003 mm thick.

4. Placing between Paper

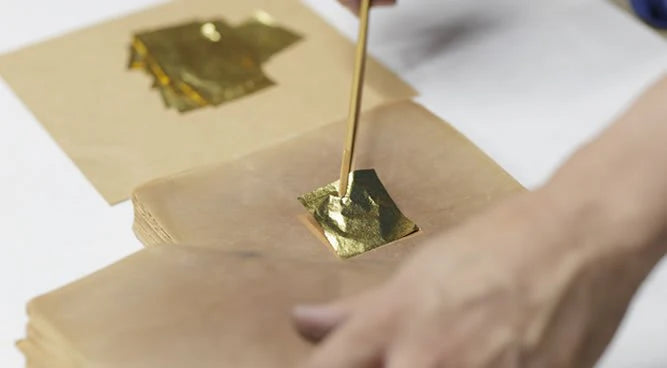

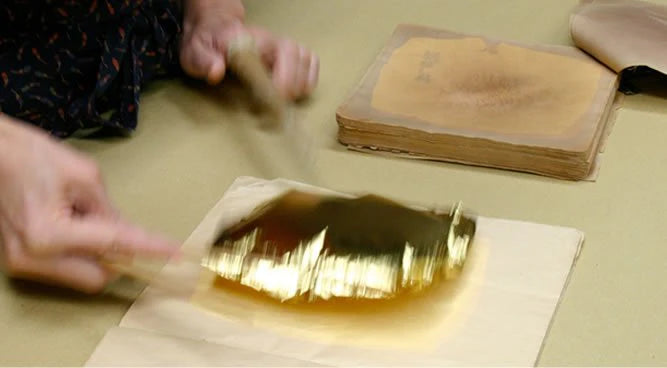

The uwazumi, about 0.003 mm thick, is further worked into leaves measuring 0.01–0.02 mm in thickness. Each uwazumi is cut into twelve pieces, which are then called koma. At this stage, the koma sheets are placed one by one between layers of rough pounding paper.

5. Final Pounding

The thin gold leaves, placed between rough pounding papers, are secured with leather and hammered by a metal pounding machine. Once thinned to the desired level, the leaves are transferred to fine pounding paper called omogami and pounded further until they reach about 0.01 mm in thickness.

6. Removal from Paper

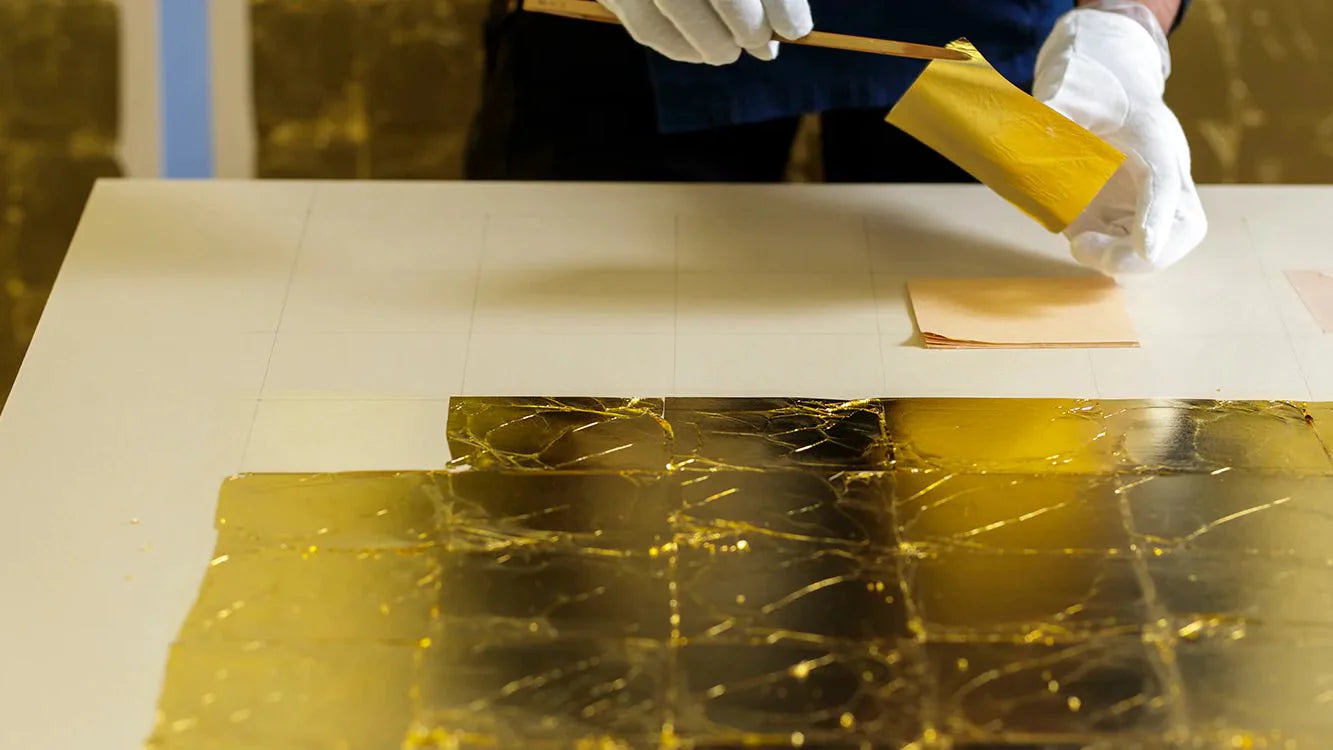

Once completed, each sheet of gold leaf is transferred to a stack of paper called hiromonocho after quality inspection. Bamboo tweezers and paper finger covers are used to prevent static. This step requires extremely delicate handiwork, as the leaf, only about 0.01 mm thick, can tear at the slightest breath of air or a trace of static.

7. Transferring and grading

In the final stage, the edges of the leaves in the hiromonocho are trimmed. The finished leaves are then stacked in groups of one hundred sheets for final assessment. After grading, they are temporarily stored in a box until they are cut to size.

Gold leaf is sold in four standard sizes: 10.9 cm (4.3 in), 12.7 cm (5 in), 15.8 cm (6.2 in), and 21.2 cm (8.3 in) squares. The leaves are trimmed with special cutting frames and then placed onto a type of Japanese paper known as kirigami, meaning “cut paper.”

Makers

Filters