The Secret Behind the Beauty of the Japanese Sword

Written by Ito Ryo

As last year’s hit TV drama Shogun vividly reminded us, the samurai are among the most iconic symbols of Japan’s rich cultural history.

One emblem of these warriors is the katana—a traditional sword, formally known as the “Japanese sword.” Up until the Edo period (1603–1868 CE), when the samurai class ruled the nation, these blades were produced in large numbers. However, with the modernization and Westernization efforts that began in the Meiji era (1868 –1912 CE), the samurai as a class disappeared, and ordinary citizens were banned from carrying swords, causing demand to plummet. This downward trend continued, and after World War II, the manufacture and possession of swords, except as works of art, were prohibited.

Today, the number of specialized craftsmen known as katanakaji “swordsmiths,” who forge the blades of these legendary swords, has dwindled rapidly. With an aging workforce and declining orders, it’s estimated that as of May 2024, only about 70 to 80 active swordsmiths remain across Japan.

Amid these challenging times, I happened to learn about a company called Nippon Genshosha—a venture founded by three young swordsmiths who decided to defy the tide and dive into the world of traditional Japanese sword-making. They left Tokyo, the historic hub where these techniques were honed, and relocated to Kyoto, far from the capital, to establish a new workshop where they practice their craft daily.

“I’d love to meet them and find out firsthand what motivates their work. I want to see their workshop and their creations with my own eyes.”

Driven by that deep sense of curiosity and admiration, I, Fusada Mototsugu (CEO of MUSUBI LAB), went to visit them myself. What followed was an experience filled with surprises, discoveries, and heartfelt inspiration.

Table of contents

What Is a Japanese Sword? – How It Differs from Western Blades

Before sharing my experiences, let’s first take a brief look at what exactly a Japanese sword is.

The term “Japanese sword” refers to a broad category of iron blades that have been crafted in Japan for nearly 1,000 years. Unlike Western swords, which typically feature a straight, thick blade with a double edge designed for chopping and striking, Japanese swords are characterized by their curved, slim blades that are single-edged and ideally suited for slicing. Renowned for being “unbreakable, unyielding, and exceptionally sharp,” these blades are meticulously forged by master craftsmen known as swordsmiths, following a time-honored traditional method.

In recent years, interest in Japanese swords has surged in Japan, particularly among the younger generation, partly influenced by video games and manga. Meanwhile, in America and Europe, the cool aura of the samurai combined with the remarkable artistry of these weapons has steadily bolstered the reputation of the Japanese sword.

The Path to Swordsmithing: A Deep Passion for Japanese Swords

The company we visited this time, Nippon Genshosha, is based in Kyotango City—a coastal town about a two-hour drive north of Kyoto. Kyotango is a region renowned not only for its agriculture and fishing but also for its thriving textile and sake industries.

At a workshop nestled in a picturesque rural area—where traditional tiled-roof wooden houses line the roadside and rolling fields open up to views of gently undulating mountain ridges—we were warmly welcomed by three swordsmiths: Kuromoto, Yamazoe, and Miyagi.

All in their 30s, they sport a matching outfit consisting of a white cotton jacket resembling a kimono called a hangi paired with black hakama trousers. Their youthful and refreshing appearance was a pleasant surprise, quite different from the image I had preconceived of traditional swordsmiths. Their expressions and demeanor were equally calm and inviting.

The three have long been enamored with the “sword” ever since they were children, inspired by TV dramas, movies, and manga depicting samurai in action, and they dreamt of becoming swordsmiths. Fate intervened when all three happened to choose the same apprenticeship at the workshop of Yoshihara Yoshindo—one of Japan’s most renowned swordsmiths, whose work is celebrated overseas and is even part of the collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. His reputation is such that over half of his clientele are foreigners, and he was once commissioned by film director Steven Spielberg.

During a total preparatory period of 10 years, which included a rigorous seven-year apprenticeship under Yoshihara, the trio successfully passed the qualification exams necessary to become certified swordsmiths. Motivated by a shared passion, they decided to join forces and open their own workshop. In 2019, they established Nippon Genshosha with the aim of preserving the traditional art of Japanese sword-making while revitalizing an industry in decline.

The Japanese Sword, Forged Through the Artisans’ “Aun no Kokyu”

The Nippon Genshosha workshop and showroom, with its dark wooden and brown walls evoking the image of a Japanese castle, was completed in 2022 by repurposing the home once inhabited by the grandparents of one of the team members, Yamazoe, in Kyotango City along the coast.

Upon entering the workshop, I was greeted by a space with earthen floors laid bare—a raw, yet strikingly beautiful setting. In one corner, a work furnace blazed softly, radiating a gentle warmth that filled the room.

Our guide for the day, Kuromoto, began by showing me a large lump of tamahagane, the high-quality steel that forms the very foundation of a Japanese sword. Its surface, reminiscent of volcanic rock with rough charcoal-gray textures interspersed with hints of red, blue, and yellow, possessed a mysteriously captivating hue.

“Tamahagane is produced using the traditional ‘tatara’ method, where iron sand and charcoal are layered and heated. It’s renowned for being almost impurity-free and exceptionally uniform in quality. In Japan, this rare and costly steel is produced only in Shimane Prefecture, and it takes roughly 7 kilograms (roughly 15.4 pounds) to forge the blade for a single sword. The first step in sword-making is heating the tamahagane in the furnace and then hammering it to extend the metal to a thickness of about 3 to 6 millimeters (approximately 0.12 to 0.24 inches),” Kuromoto explained, after which I had the opportunity to witness the process firsthand.

In the furnace, tamahagane heated by fiercely burning pine charcoal glowed a brilliant yellow. Miyagi used a pair of iron pliers to extract the glowing piece and set it on an iron anvil. Following a couple of light taps from Miyagi’s small hammer, Kuromoto and Yamazoe, positioned to either side, swung a large hammer—about a meter in length—alternately, striking the tamahagane with resounding metallic “Clang! Clang!” sounds.

"Clang! Clang! Clang! Clang!"

The rhythmic, almost hypnotic sounds echoed throughout the workshop as sparks occasionally burst forth from the tamahagane.

The three artisans, having shifted to a more focused, serious demeanor, exchanged no words during this synchronized process. Instead, Miyagi signaled the start and end of their work by striking the anvil, while subtle changes in his hammering conveyed precise instructions regarding the target area and the force required. Watching their silent, seamless coordination filled me with a profound sense of quiet admiration.

“Would you like to give it a try?” Kuromoto offered, handing me a hefty hammer.

“Don’t worry about swinging it high overhead like we do. Just aim for the center of the steel and give it a solid hit,” he advised.

When I began hammering the reheated tamahagane, my mind was buzzing with the pressure of not making a misstep, and I couldn’t help but wonder if I was managing to properly extend the steel.

In this way, the tamahagane gives its first cry of life, setting the stage for its eventual transformation into a sword.

The Sword-Making Process

According to Kuromoto, who demonstrated various tools and materials, the forging of a sword involves the following steps:

1. Kowari and Sorting:

The thinly extended tamahagane is broken into small pieces roughly 2 centimeters square, separating the hard, high-carbon steel (hagane) from the softer, low-carbon steel.

2. Tsumiwakashi:

The pieces of hard and soft steel are separately gathered and stacked, then heated to about 2372°F (1300°C) before being hammered into one large mass.

3. Tanren (Folding and Forging):

Each mass—the hard steel and the soft steel produced in the previous step—is heated and repeatedly hammered to stretch it out. This process removes impurities, increases purity, and adjusts the internal carbon content to achieve the desired hardness. The steel is folded and hammered repeatedly—hard steel about 15 times and soft steel about 8 times—to create a layered structure that enhances its resilience and strength.

4. Kawagane and Shingane Production:

The soft steel (kawagane) from step 3 is shaped into a U-form, into which the hard steel shingane is wrapped. This assembly is then heated and hammered together until fully fused.

5. Sunobe and Hizukuri :

The combined mass from step 4 is reheated and hammered into a rod until it reaches the intended length and thickness. Additional hammering then shapes the tip and the blade area of the sword.

6. Tsuchioki and Quenching:

A paste called yakibatsu—made from a mixture of clay, charcoal powder, and stone powder—is applied thinly over the cutting edge and more thickly on the rest of the blade. After drying, the sword is heated to 1472–1652°F (800–900°C) and then rapidly cooled by plunging it into cold water. This quenching process transforms the steel’s microstructure, hardening only the cutting edge and imparting the signature curve of the Japanese sword.

7. Straightening and Rough Sharpening:

Any distortions or unwanted curvatures resulting from the quenching are corrected by additional hammering, and the blade’s edge is roughly sharpened.

Completing all these intricate steps takes approximately two weeks to one month. Following this, a specialist known as a togishi “sharpener” performs the final polishing and honing—a process that is both labor-intensive and time-consuming. Due to the limited number of skilled togishi, this final stage can take anywhere from six months to two years. Once the blade returns to the swordsmith, it is further refined by filing, and the grip is drilled and stamped with the craftsman’s name, marking a provisional completion of the sword.

Every aspect of this craft—from fabricating the tools to the handcrafting of the sword itself—demands tremendous effort and time. Today’s Japanese sword-making adheres strictly to these ancient, high-cost methods in order to preserve traditional techniques. In our modern, efficiency-driven society, the continuation of such a meticulous and time-honored process exudes a profound sense of nobility. It stands in stark contrast to the mass-produced items churned out by industrial machinery.

With these thoughts in mind, I left the workshop and soon followed Kuromoto’s guidance to a separate showroom.

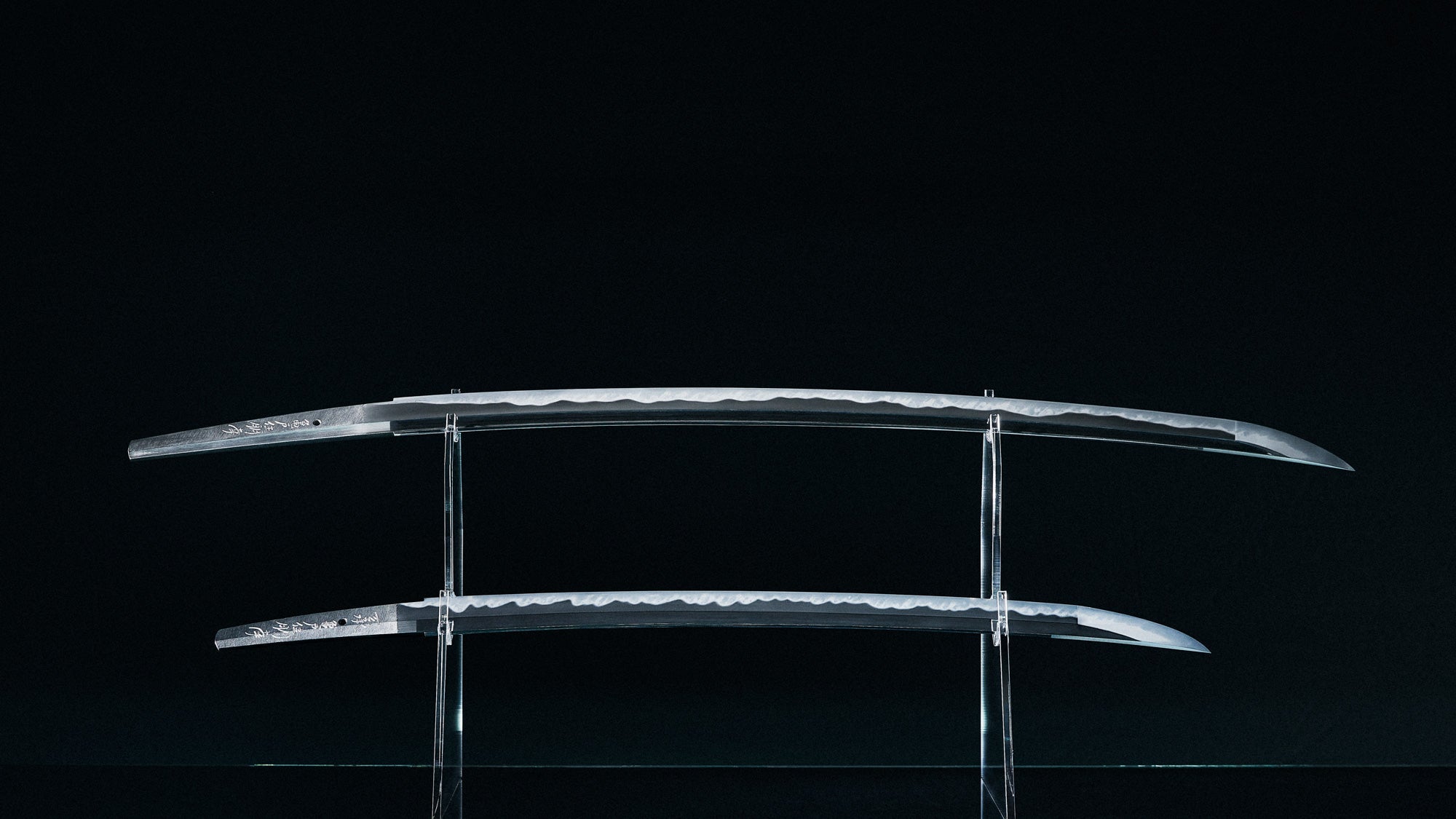

The Completed Blade's Heart-Stirring Beauty

Right next to the workshop, the showroom's entrance and the floor at the threshold are laid with smooth pebbles, and a large white noren featuring a stylized logo of the character “玄” from Nippon Genshosha hangs gracefully.

Stepping through the noren, I entered a traditional Japanese space with high ceilings adorned with white walls and robust, dark brown wooden pillars and beams. The concrete floor is fitted with modern furniture such as tables and chairs, blending contemporary design with touches of timeless beauty.

I was invited to see a blade crafted by Kuromoto himself. To avoid damaging the sword, I first removed my watch and put on a pair of thin fabric gloves to prevent any rust from skin oils. Carefully, I held the grip with one hand while laying the blade horizontally on a handkerchief-like cloth held in the palm of my other hand. I then slowly turned the approximately 70-centimeter 70-centimeter (about 27.6-inch) blade over, admiring both its front and back.

This was the first Japanese sword I had ever held. Although the blade is generally said to weigh less than 1 kilogram (about 2.2 pounds), it felt astonishingly heavy, as if it easily exceeded that weight.

Bathed in the radiant light from overhead, the blade’s design is impeccably efficient, exuding both power and overwhelming beauty. I was so captivated that I lost track of my words. Amid the awe of holding a weapon designed to take lives, I also felt deep reverence and admiration for this extraordinary work of art—a complex, intense mix of emotions unlike anything I had ever experienced.

Three Essential Elements That Define the Beauty of a Japanese Sword

According to Kuromoto’s explanation, there are three key aspects to appreciate when examining a sword.

The first is its sugata, or overall form. Historically, Japanese swords evolved in length, width, and curvature in response to changes in combat tactics and needs. For example, one defining feature of a Japanese sword—the curve, known as sori—illustrates this evolution. Prior to the 8th-century Nara period (710–784 AD), blades were straight to facilitate thrusting and cutting. However, from the late Heian period (around the 11th to 12th centuries), the design shifted to a curved form, optimized for swift drawing and slashing from horseback.

The second point is jigane, referring to the patterns visible on parts of the blade other than the cutting edge. These patterns are created during the “folding and forging” process described earlier. Resembling the textures of wood or tree bark, these markings vary widely depending on the region, school, or individual swordsmith responsible for the creation.

The third element is the hammon—the wavy pattern that appears along the junction between the blade and the jigane as a result of the quenching process. This feature can take many forms—reminiscent of a string of flower buds, waves, clusters of trees, or even flames. The artful application of the yakibatsu “quenching clay” is key to achieving the desired hamon, showcasing the swordsmith’s skill. While swords made before the Edo period often featured hamon inspired by natural forms, advancements in technique during the Edo period led to designs influenced by man-made motifs such as beads juzu, and bamboo blinds sudare.

“Both the jigane and hamon, along with the sword’s curvature, are essential elements of a Japanese sword’s artistic appeal. They are, at their core, expressions of ‘functional beauty’—byproducts of the rigorous process required to create a high-quality blade that is unbreakable, unyielding, and exceptionally sharp,” Kuromoto explained.

He even shared an intriguing anecdote with me: “According to the latest theories, there were actually not many instances of samurai using swords on the battlefield. Weapons like bows, arrows, and spears, which allowed them to keep their distance, were far more common. Swords tended to be used only when all other options had been exhausted or when combat devolved into very close-quarters fighting. The dramatic, sword-swinging battle scenes often portrayed in TV dramas and films do not always reflect historical reality.”

Kuromoto continued, “Nevertheless, a sword was always carried into battle by a samurai. It served a practical purpose in the final moments when all other means of combat were depleted, and under extreme circumstances, it became a vital support for the warrior’s spirit. Over time, the sword also came to be seen as a kind of talisman embodying the wish for victory in battle and the prosperity of one’s family, as well as a treasured heirloom to be passed down through generations. This evolving demand for a sword that was not only more beautiful and durable but also exceptionally sharp drove successive generations of swordsmiths to continuously refine their craft.”

“Today, as modern swordsmiths, we are committed to preserving these traditional techniques while also evolving them to meet the needs of our time.”

Nippon Genshosha’s Vision for the Future of the Japanese Sword

In the past, owning an exceptional sword was a symbol of a samurai’s status. One of Kuromoto and his team’s goals is to restore that historical prestige—to create such captivating blades that people would aspire to own them once again.

To achieve this, Nippon Genshosha is dedicated to sharing the remarkable allure of Japanese swords with as many people as possible. In between productions, they offer guided tours for the general public, giving visitors a firsthand experience of the craft.

They are also pioneering innovative ways to appreciate Japanese swords. This includes proposals for modern display styles, such as large art pieces featuring a full sword encapsulated in clear epoxy resin that complements contemporary living spaces, as well as crafting everyday items like kitchen knives and letter openers that utilize traditional sword-making techniques. Moreover, they are actively engaging audiences through YouTube and social media.

Interestingly, Kyotango City itself is steeped in sword-related history, boasting ancient ironworks ruins and legends associated with swords at several shrines. “Here in Kyotango, we are even considering a unique approach: capturing the natural scenery, like the sea and mountains that we can see every day—within the hamon of our swords,” Kuromoto shared.

The Japanese swords newly crafted by modern swordsmiths, including those from Nippon Genshosha, command prices in the range of several million yen each—they are by no means inexpensive. However, as detailed in this article, their high cost is a reflection of the rare materials, advanced techniques, and the immense amount of labor and time devoted to handcrafting each blade.

In my view, much like the Japanese saying "a sword is the soul of a samurai," which signifies that a sword holds the spirit of its owner, the spiritual dimension of these blades will become even more essential in future creations.

I once heard from Kuromoto of an occasion during the samurai era when a warrior presented a specially made sword, with two different hamon on either side of the blade, each embodying a specific wish, to a superior. Imagine gifting a sword that encapsulates prayers for happiness, prosperity, safety, or health, or one that captures memories of a cherished landscape or a significant life milestone. Such a conception of the Japanese sword—as a treasured heirloom to be cherished and passed down through generations—holds a unique allure.

The three artisans at Nippon Genshosha are deeply rooted in a tradition that spans a thousand years. With the solid craftsmanship they honed under their master, Yoshihara, and the fresh, innovative vision unique to their youth, I eagerly look forward to the new expressions of beauty they will bring to Japanese sword-making.

Nippon Genshosha

314 Tangocho Miyake, Kyotango-shi, Kyoto

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.