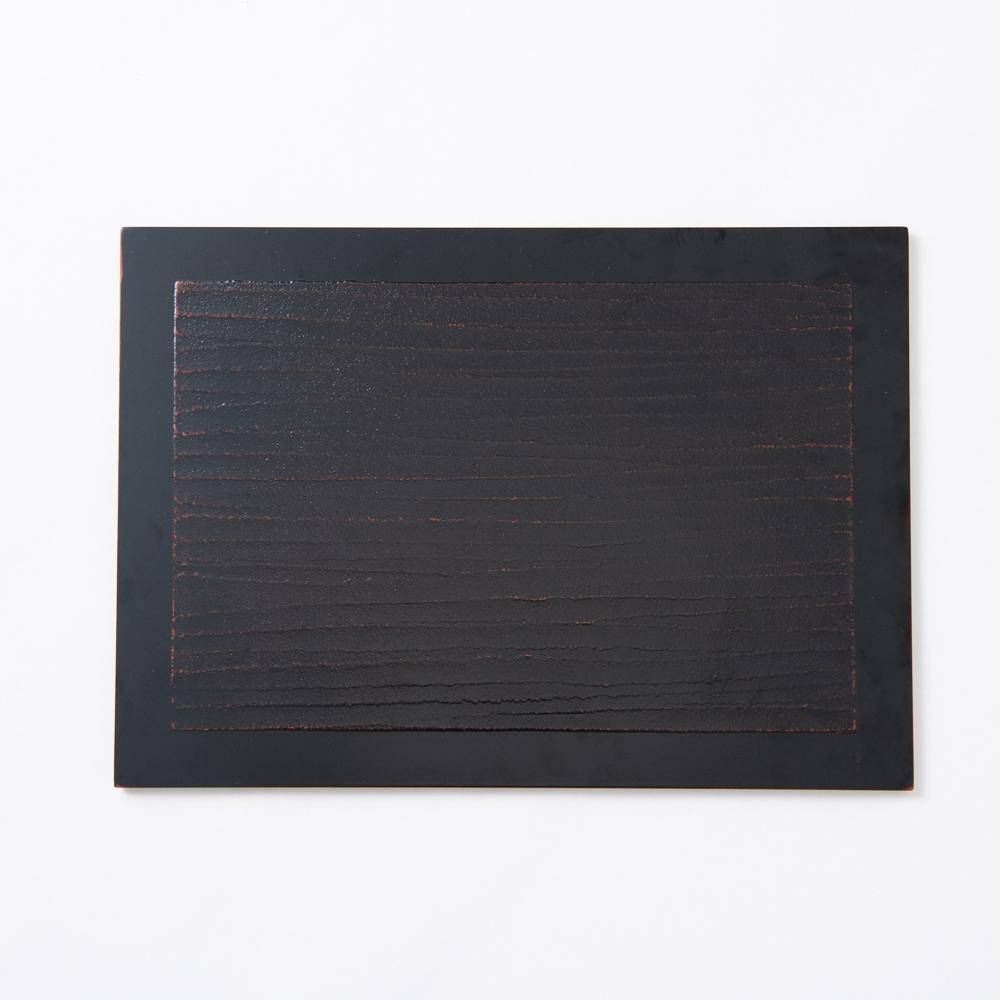

Lacquerware

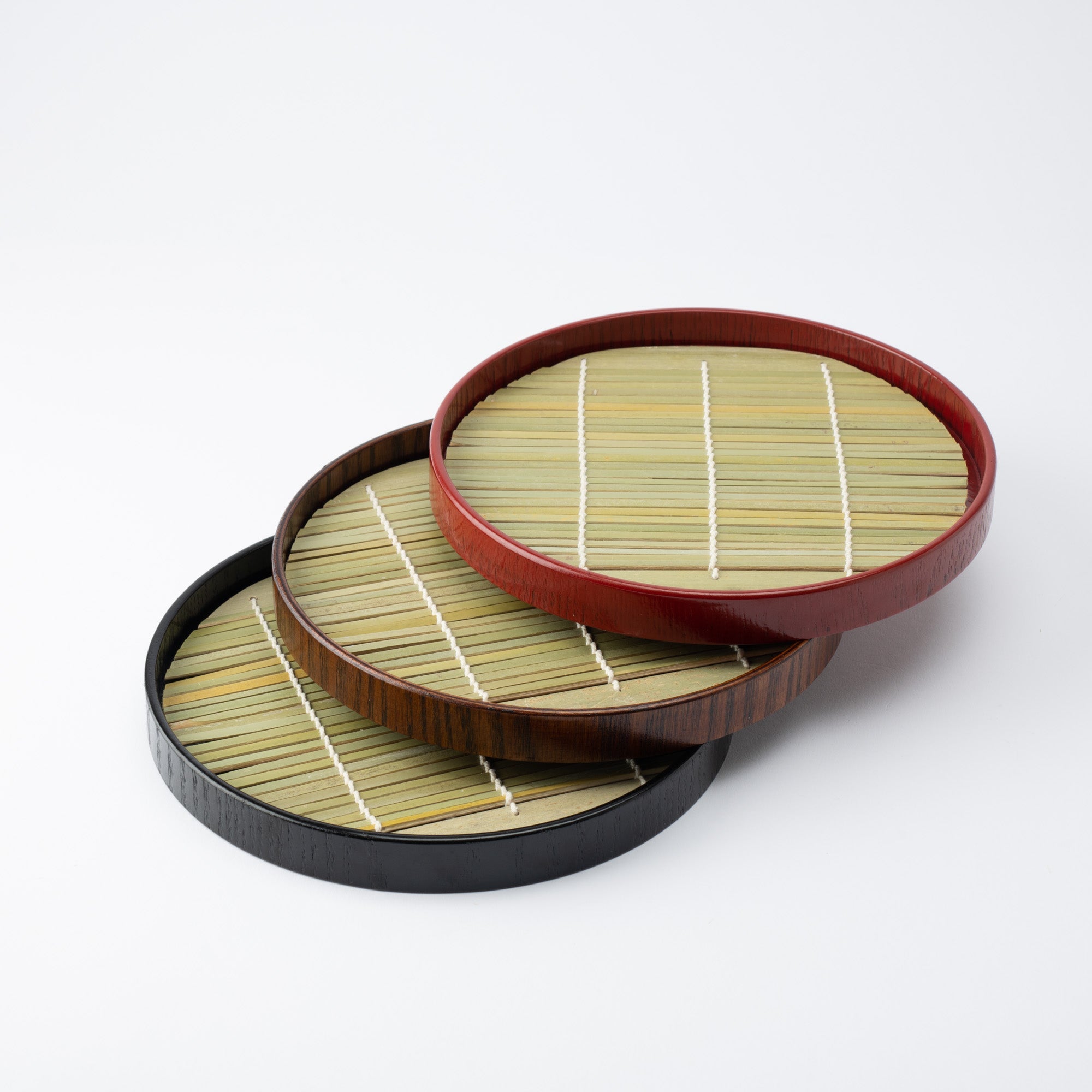

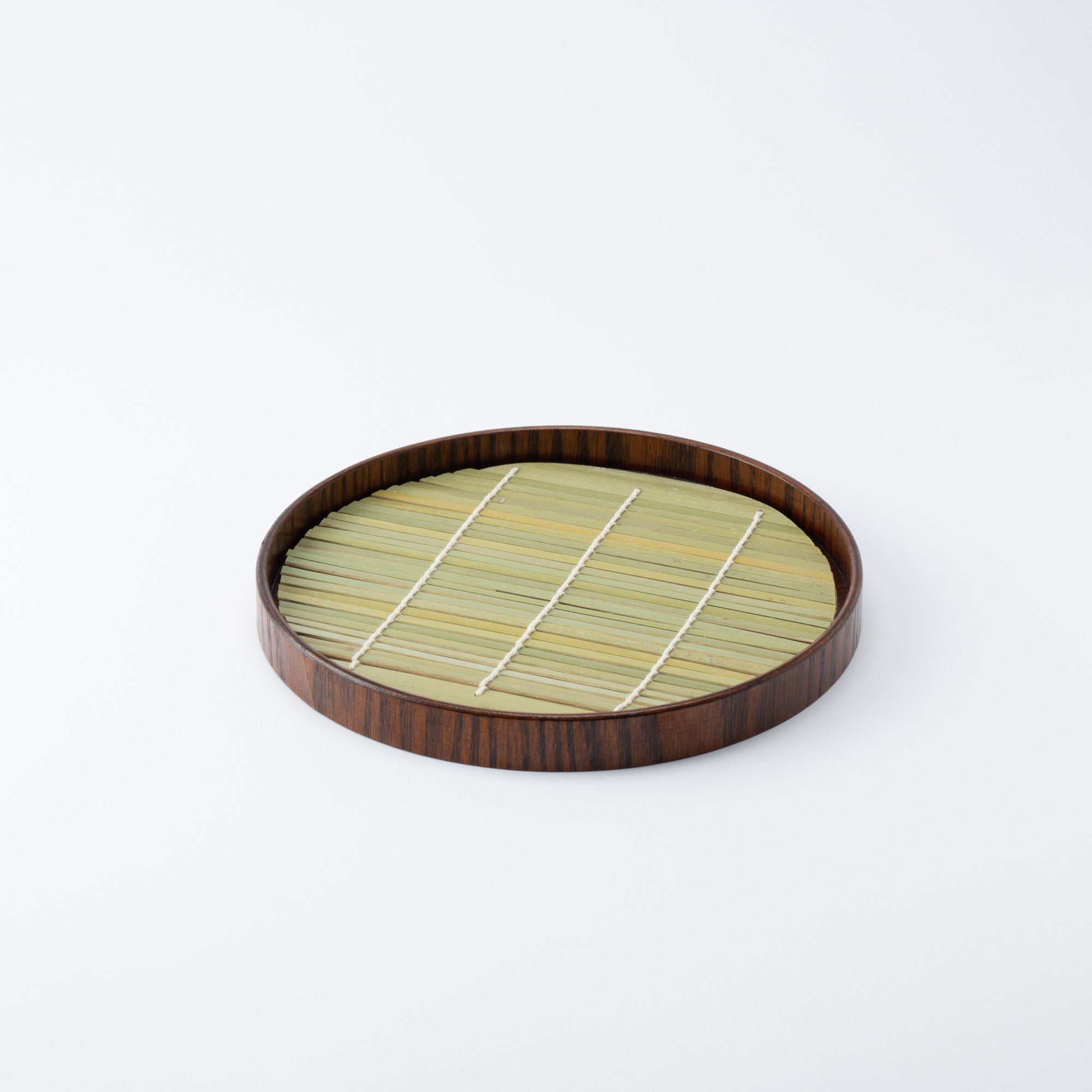

Japanese lacquerware, also called shikki in Japanese, is a proud handicraft with a long history dating back to 5,000 BCE, and traditional methods are still followed today. Durable, light, antibacterial, and robust enough to endure for more than one hundred years, Japanese lacquerware is not only beautiful, but also highly functional.

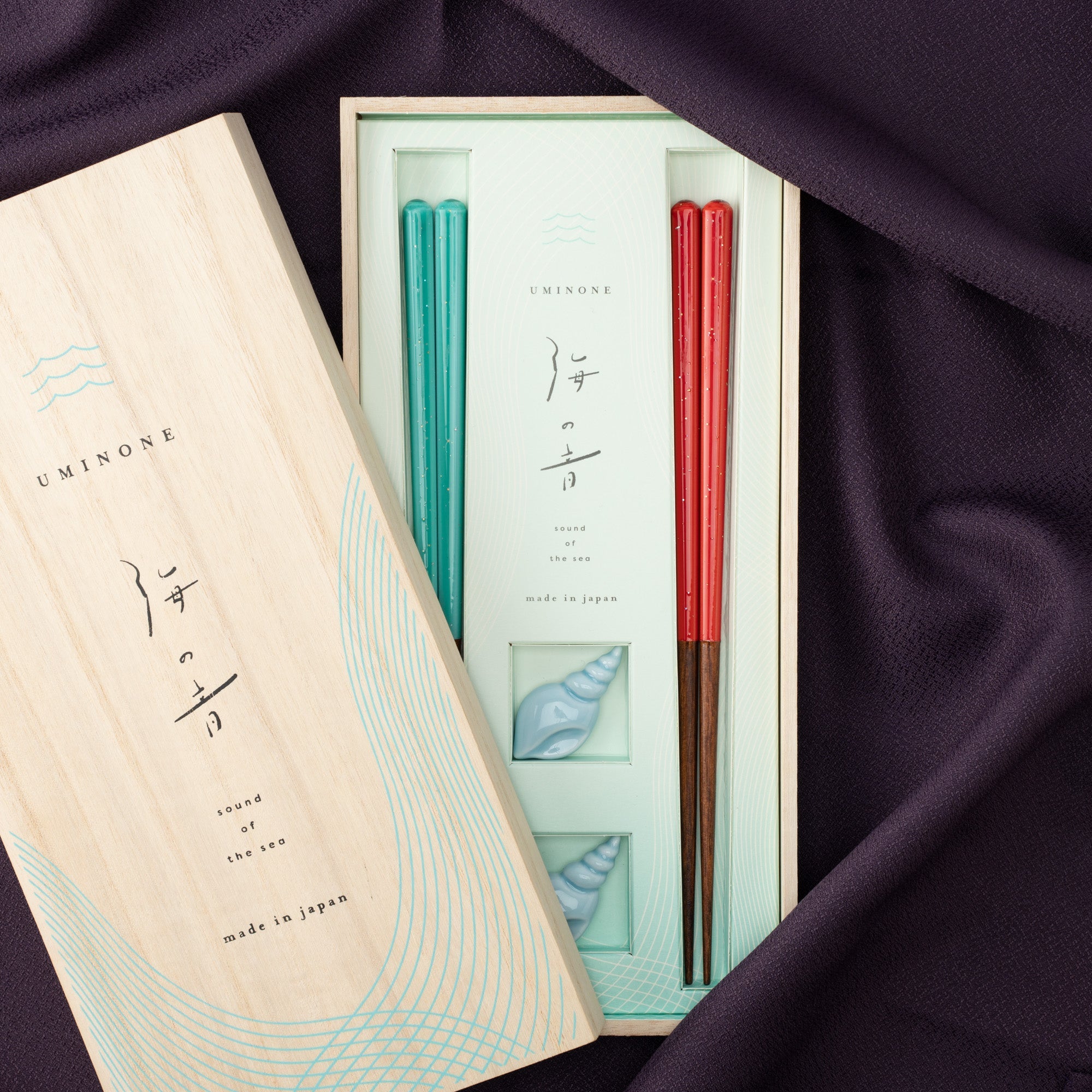

In addition to the fine Japanese lacquerware found in antique and vintage pieces, there is also contemporary Japanese lacquerware suitable for modern life made by artisans who continue to improve their skills and pass on tradition today.

Japanese lacquerware is a time-honored tradition that dates back about 7,000 years to Japan's prehistoric era. The special lacquer, urushi, is produced and processed from the sap of the urushi tree, which grows naturally in East Asia.

The antibacterial properties of urushiol, the main component of urushi lacquer, continue even after curing, making Japanese lacquerware products hygienic tools that prevent the growth of bacteria.

Japanese lacquerware is not only beautiful, with its unique transparent shine, but also very robust and resistant to deterioration, acid, and alkali. Moreover, lacquerware’s long history shows that these eco-friendly items can be used continuously and still retain their beauty.

In recent years, many lacquerware items have been made with dishwasher-safe resin or safe-chemical paints. The production of these lacquerware works is supported by the skills of craftspeople trained in Japan.

The history of Japanese Lacquerware dates back to the Jomon period. The world's oldest lacquerware was discovered in Hakodate, Hokkaido, and the world's oldest piece of Urushi ( lacquer tree) from about 12,600 years ago was found in the Torihama shell mound in Wakasa, Fukui Prefecture.

During the early Jomon period (about 9,000 years ago), lacquered clothing was found, and during the late Jomon period, wooden Lacquerware and many other daily utensils were found at Jomon sites throughout Japan, and later, during the Yayoi period (300 BC-300 AD), the uses of lacquer became more diverse, from farming tools to fishing tools.

After the arrival of Buddhism from the continent in the Asuka period (538-710), the role of lacquerware became important for artistic purposes. Temples, Buddhist statues, and Buddhist utensils required a large amount of Urushi lacquer, and a governmental lacquerware organization was established. The famous "Tamamushi no Zushi (Shrine of the Jewel Beetle)" at Horyuji Temple is a lacquered wooden object, and lacquer was also used to glue the wings of the beetle and to paint the sides.

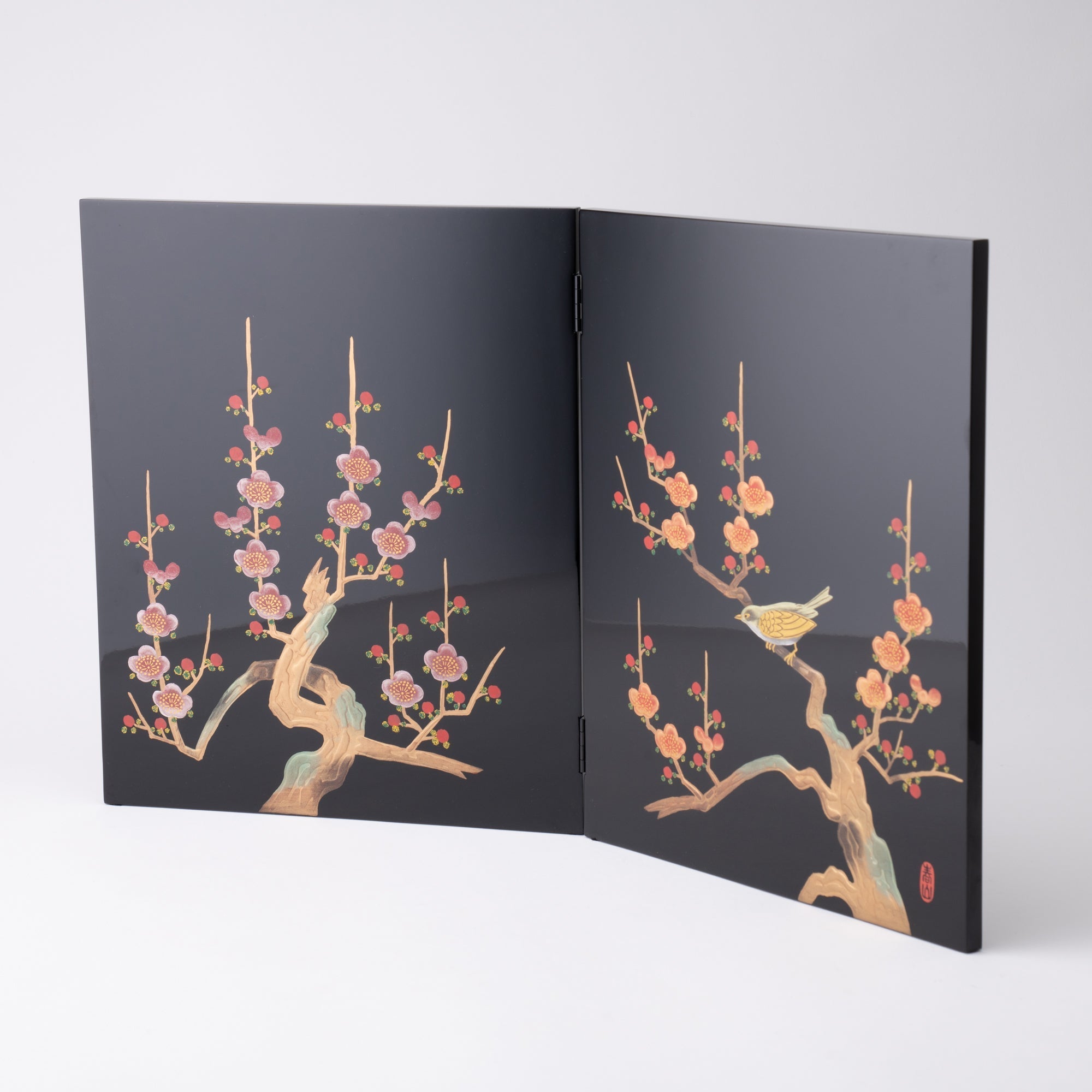

From the Kamakura period (1185-1333), there was a division of labor in the processes of base preparation, lacquering, and decoration. With the emergence of specialized craftsmen, the techniques of Raden and Maki-e were further improved. On the other hand, with the development of the spinning-lathe, lacquering became popular for tableware and furnishings used by the Japanese nobility. At the same time, vermillion and black lacquer were also used for daily utensils for monks and armor for samurai.

In the Edo period (1603-1868), when there were no more major wars, Japanese Lacquerware evolved into a uniquely Japanese art form. Each domain encouraged the production of lacquerware, and distinctive works of lacquerware began to appear in each region of Japan.

In the Meiji period (1868-1912), the government exhibited Japanese Lacquerware at the World Exposition held in Europe. They were highly acclaimed as representative Japanese crafts. Today, the world of lacquerware is facing the same challenges as other crafts, such as the shortage of successors and the passing on of techniques, but the lacquer culture that has been handed down from generation to generation is still an essential part of Japanese lifestyle culture.

The Urushi lacquer used in Japanese lacquerware is a resin refined from the sap secreted when the Urushi tree is scratched. The Urushi tree is a deciduous tree widely distributed throughout East Asia, including Japan, the Korean Peninsula, and China, and Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar. In Japan, it is a deciduous tree that grows in a wide area from Kyushu to Hokkaido. The largest trees can reach a height of 32 ft.

The collected Urushi sap is purified by heating and stirring it with a stirrer to remove debris. The main component of Urushi is called urushiol, and the higher the quality of the lacquer, the higher the content of this component. The urushiol hardens by taking in oxygen from the moisture in the air, so it does not cause sick building syndrome, unlike chemical paints, which release toxic substances into the air as the solvent evaporates. Urushi lacquer is a natural paint that is harmless when hardened, making it safe for human health and the natural environment.

All of the Japanese Lacquerware we carry at Musubi Kiln is high level of safety. The cured lacquer is a non-toxic, chemical-free, organic material.

If you have a child in your home, you may be worried about rashes caused by Urushi lacquer, but it is not uncommon to get rashes from well-cured Urushi lacquer. Urushiol, the main component of Urushi lacquer, is a natural ingredient with high antibacterial properties, and it kills resistant Staphylococcus aureus, O-157, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, etc. on the surface of lacquerware in 6 hours. It is a good choice for tableware for children because of its heat-blocking properties and durability.

Related posts

Filters