Japanese Food Culture and Seasonalities

Written by Team MUSUBI

The seasons hold great significance in Japanese culture and are deeply ingrained in the traditions, customs, and way of life of its people. One representative way in which seasonal changes are celebrated is through food.

Japan has a long history of gathering and eating the most nutritious foods available during each season. The importance of doing so is explored and explained through Japanese words such as "shun" and "hatsumono." Here we will introduce the connection between Japanese food culture and the seasons as well as the etymology of shun and hatsumono.

tables of contents

Japanese Food Culture and the Seasons

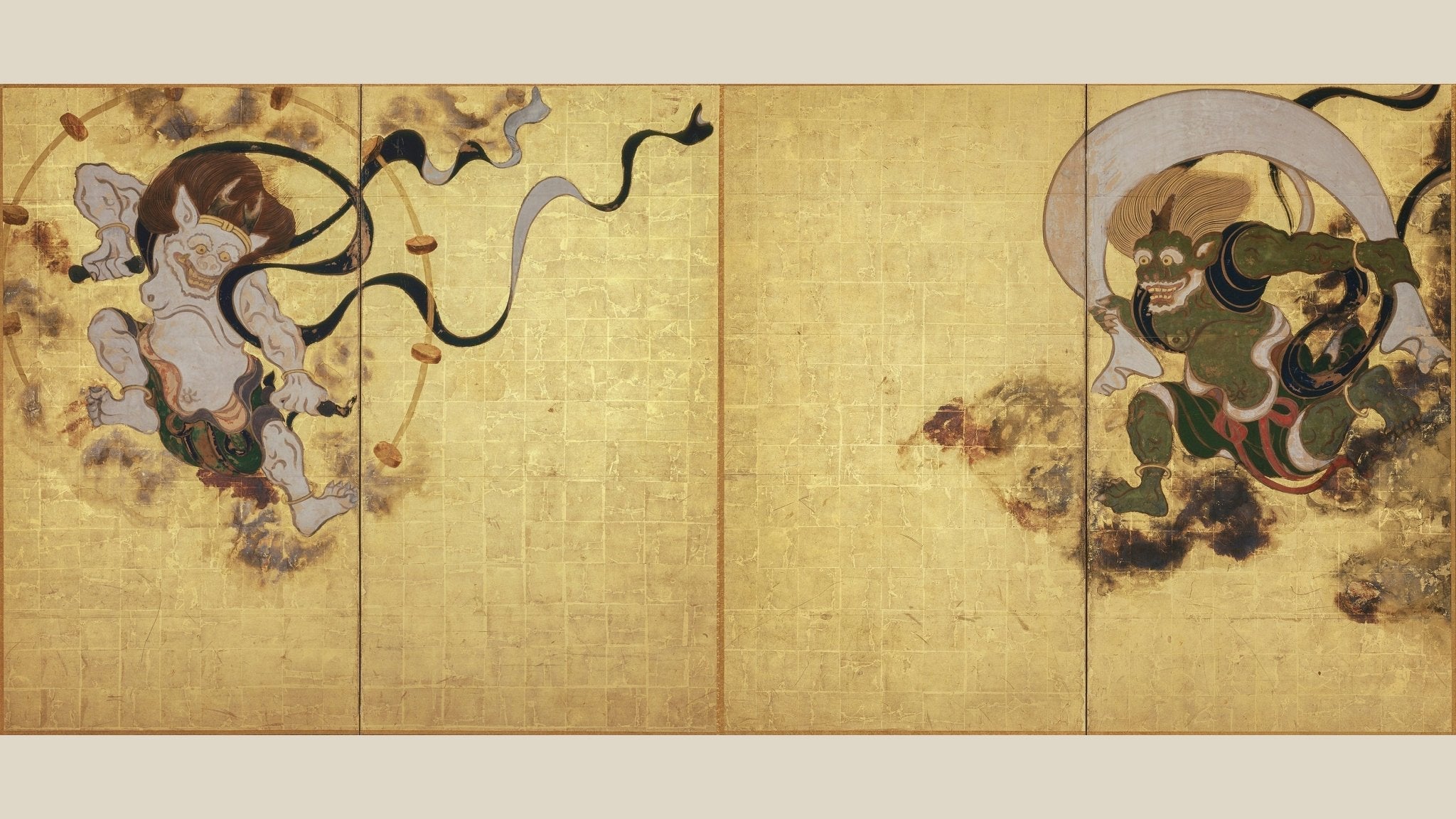

Additionally, seasonal dishes are seen as a way to celebrate the changing of the year and the newest ingredients. This practice helps to create a connection between the food and the natural environment, as well as to honor the changing seasons.

A prime example of this is Kaiseki cuisine. Kaiseki cuisine is a traditional Japanese multi-course meal that emphasizes seasonality, balance, and presentation. It typically consists of an appetizer, soup, sashimi, grilled fish, a simmered dish, and a steamed dish, followed by a pickled dish, a rice dish, and a sweet dessert.

Sen no Rikyu pursued ichi-go ichi-e through making his Kaiseki courses one-of-a-kind. It's said that, at one point, Rikyu even picked all the flowers in his garden, just to display and make one blossom stand out during a course. The current style of Kaiseki courses may vary based on the chef, but the general principles remain the same. Kaiseki cuisine is often considered to be the pinnacle of Japanese culinary art.

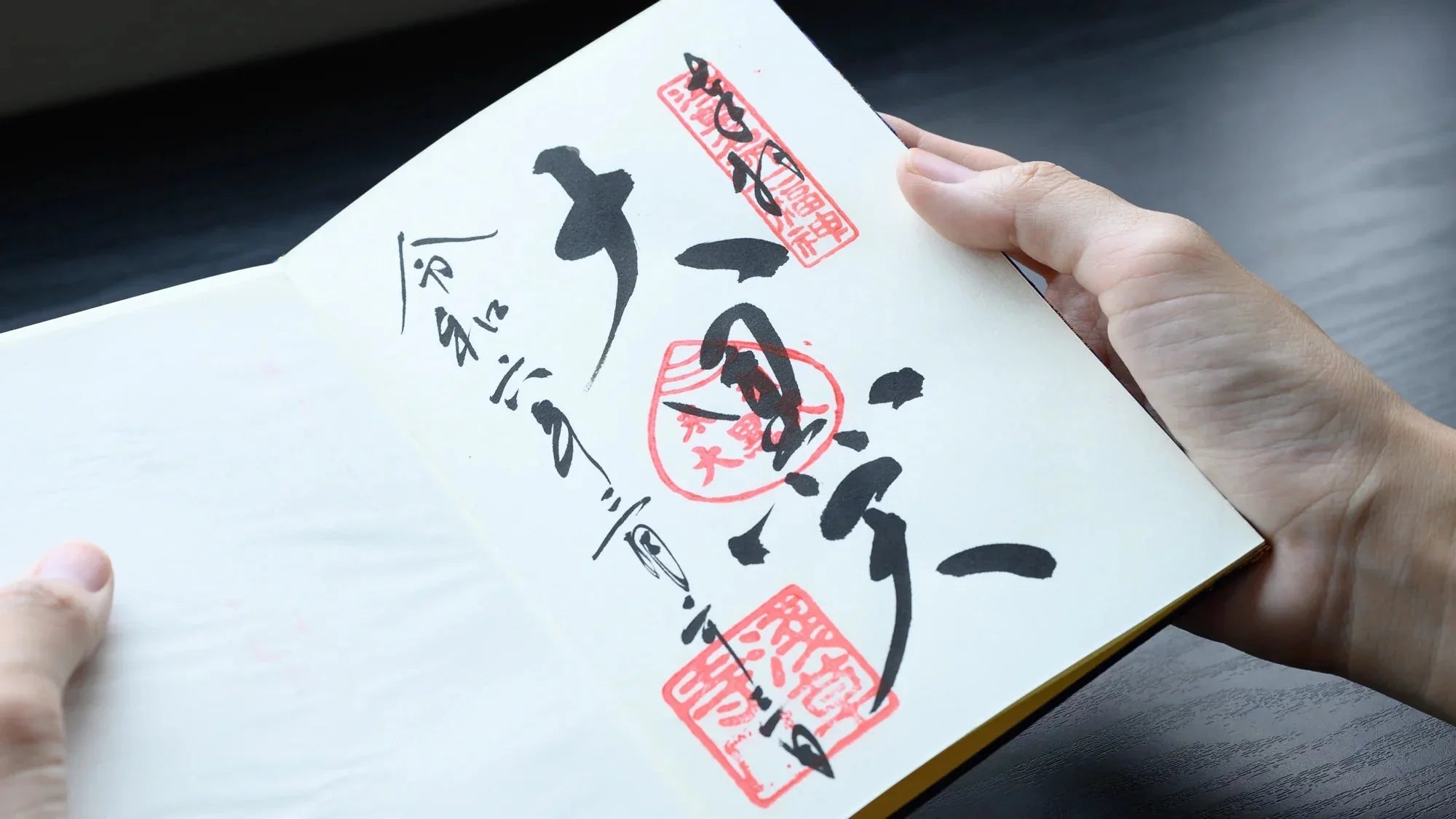

Shun

The written character for "shun" is originally Chinese and refers to a period of ten days. When adopted into the Japanese language, shun also came to mean the best time of the year for specific foods.

What's more, in ancient times, ceremonies held at the beginning of each season and at the start of the second half of the month were called shun. Festivities typically consisted of a banquet filled with seasonal delicacies, held for the emperor to listen to and discuss government affairs with his subjects.

After the mid-Heian period (c. 794-1185), shun ceremonies were held only on April 1st and October 1st. The April ceremony was called "Moka-no-shun" (early summer seasonalities) and the October ceremony "Moto-no-shun" (early winter seasonalities). These two ceremonious months were collectively known as "Nimo-no-shun" (the two beginning seasonalities).

As aforementioned, shun is a period when seasonal foods are harvested and eaten. This season is further divided into three periods when foods are the most available and delicious.

"Hashiri" (beginning) refers to the starting period of shun, when seasonal foods are first sold on the market. First foods during the hashiri period are called hatsumono, and are especially fresh. The middle period of shun is known as "Sakari" (peak), and foods during this time are ripe, readily available, and reasonably priced. The last period of shun is "Nagori" (lingering traces), in which seasonal foods slowly start to disappear from markets and the process of welcoming a new season begins. One period of shun isn't necessarily better than the other, and all offer unique ways to enjoy seasonal food.

Moreover, shun is tied to celebratory foods for festivities enjoyed throughout this year. This includes "osechi" (New Year's feast) and mackerel sushi eaten during harvest festivals in October.

Hatsumono

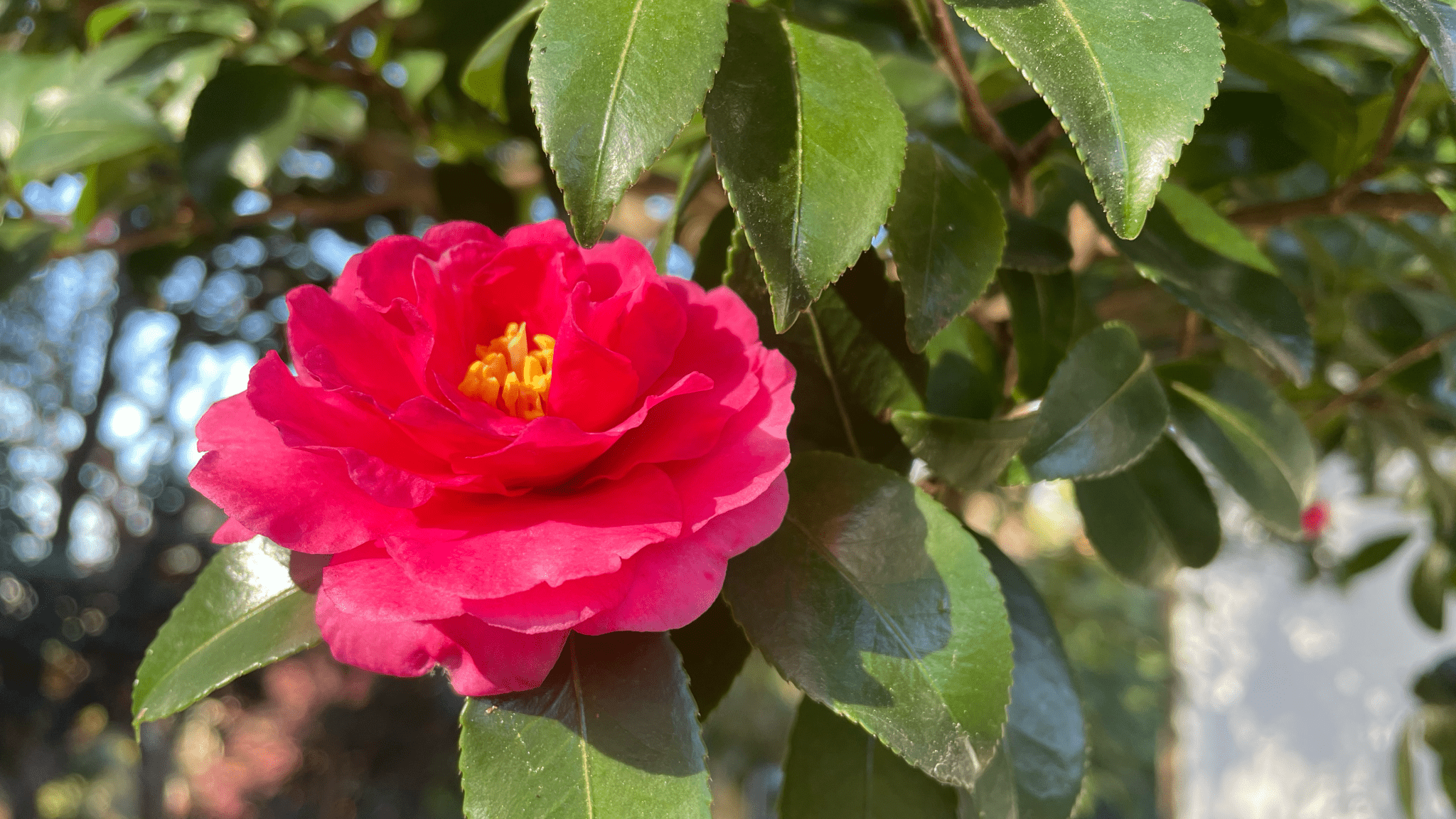

Japanese people have always valued seasonal foods and have learned to acquire them when they are at their peak.

Hatsumono refers to ingredients that are harvested or caught for the first time during a certain season or shun. Hatsumono has been rumored to bring good luck and prolong one's life by 75 days.

There are various theories as to why this is. One comes from the Chinese theory of the five elements which states that a seedling takes approximately 75 days to germinate, grow, and be ready for harvest.

Moreover, eating hatsumono with a smile while facing a certain direction was believed to bring fortune. The people of Edo (currently Tokyo) faced west to express gratitude to Buddha, who occupied Buddhist paradise in the west, for the first bounties collected every season.

Hatsumono was highly popularized during the Edo period (c. 1603-1867) as culture shifted to value fortune-bringing foods and spending money in a stylish manner. Hatsumono foods included tea, bamboo shoots, pumpkin, mandarin oranges, and sake. Competition for such items gradually escalated and eventually led to restrictions against excessive price hikes.

Later, the focus on hatsumono foods relaxed due to production and freezing technologies as well as the diversification of eating habits.

Though modernization and industrialization has made food more accessible, shun and hatsumono are still widely cherished in Japanese food culture. Seasonal foods are celebrated through holidays and traditional kaiseki cuisine–nourishing both body and soul.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.